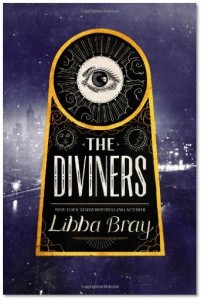

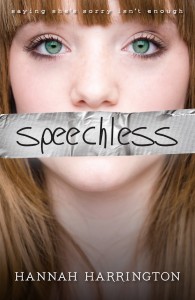

Speechless by Hannah Harrington is a young adult novel published by Harlequin Teen. Being an “older adult,” my only memories of Harlequin include watching ladies with curlers in their hair read the thin paperbacks at the laundromat mid-week, ignoring the end of the drying cycle until they had finished whatever scene it was that held them so enraptured. So, first I had to get over that preconceived notion.

What drew me to this particular book was the promotional materials, which touted it as a book about teen bullying. My school had just brought The Bullycide Project to our campus for a performance, so I was interested in what kind of light Harrington might shed on this social issue. Considering it was Harlequin, I figured it would be what we have come to expect from that publisher: raw, uncensored detail. I got that part right, but the book actually isn’t so much about the issue of bullying as it is about the issue of gay teens coming out and being outed, teen friendships as a matter of survival, and teens treading very tenuous relationships with one another on a daily basis. Teens and sexuality? Sure, but not so much. Bullying? Sure, but only as a course of response to the other issues going on.

In the first few pages of the book, Chelsea, the main character of the story, big-mouth, mean-spirited gossipy Chelsea, drunk at her best friend’s house party, interrupts two male peers in a romantic encounter. Stunned by the discovery, she returns to the party throng and blurts out what she has seen. The two boys, their passions diffused, leave the party, and a group of homophobic jocks follow. And it happens exactly as you hoped it wouldn’t: the jocks beat up one of the gay male teens so badly he’s hospitalized. Chelsea knows who did it. Her best friend Kirsten knows who did it, because it was her jock boyfriend and his buddies. Kirsten demands Chelsea not tell, and Chelsea, weighing out the benefits of popularity and being in the “in” crowd with the guilt of knowing she needs to do what’s right, tells her parents and, subsequently, the police.

The speechlessness that follows all of this gossiping and blurting and outing is Chelsea’s vow of silence, taken to punish herself for being such a loud-mouth, but also, as she discovers, to save herself from the person she was, to allow herself some “think time” to consider who she really wants to be, and eventually, as the story unfolds, to give herself the opportunity to become that person.

Having a main character in a young adult novel being speechless is a bold approach. Instead of being able to see the character through her words to others, readers see her through her thoughts, which are multifaceted, confused, constantly weighing options. This could be disastrous writing – being inside the incessant chatter of the internal monologue of a teenager who is being targeted and ostracized by her peers, dealing with her own guilt, and trying to build new friendships. But Harrington handles it cleanly, without a lot of unnecessary repetition or excessive dead-end angst.

Chelsea begins as a stereotypical superficial teen, but becomes more aware of this as the story progresses, yet she struggles to give it up:

I’m not great at a lot, but I’m good at being Kirsten’s friend. Or, I was, until I messed it all up for myself on a stupid whim. I liked it, being in her orbit. Girls wanted to be us. Guys wanted to date us. Even those who hated us wanted a look. I loved that, loved that I mattered, that people were jealous. I loved turning heads. It didn’t matter that most of them were looking at Kirsten; I was in their line of vision, and that totally counted for something. Being on that radar at all. It made me more than average. It was everything to me.

Kirsten ditches Chelsea, of course, because Kirsten’s boyfriend is now the prime suspect in the assault – thanks to Chelsea “ratting him out.” For this, she suffers Kirsten’s vengeance and drops from her place on the popularity pedestal to that of being the victim. This is where the bullying comes into the story, and not to define what is or isn’t bullying, but this isn’t the kind we hear about that causes kids to react in extreme ways – the kind of senseless picking on someone just because of the way the look, talk, dress, for no reason at all, etc. This is one character feeling wronged and taking it out on the other. Teen vengeance. But these vengeful acts also provide a backstory to Chelsea’s role as a bully, as she suddenly now becomes the target: “. . . but obviously the past week has, if nothing else, shown that I severely underestimated what it’s like to be on the receiving end of Kristen & Co.’s bullshit.” Chelsea, of course, having once been a member of the “& Co.”

There’s no question that Chelsea is the target of harassment, and goes to school fearing for her safety: her locker is repeatedly vandalized with profanity (once right while she stands and watches), her car is vandalized, and drunk-night photos only friends should see get spread electronically and via paper postering throughout the school. Through it all, Chelsea keeps her silence and takes the abuse as her “due,” at one point even taunting Kristen to “bring it,” but continually blaming herself for outing Noah and his subsequently ending up in the hospital.

The outing and attack allow this story to examine LGBTQ issues among teens. In the interview included at the end of the book, Harrington explains how the National Day of Silence was actually the inspiration for Speechless: “I always thought it was a great exercise, and had me thinking what it would be like for someone who is very verbal to voluntarily give up their speech for an extended period of time – how they might cope and what could lead someone like that to that decision in the first place.” We always hope that out of tragedy will come some good, and in Speechless, the attack on Noah leads students at the school to start an LGBTQ support group/safe zone.

That Speechless was promoted as a book about bullying, I have to wonder. This may be a better way to get it into the hands of teens who connect with that issue (or adults like me who do), but I would have made the same connection had it been promoted with the LGBTQ focus. This, however, might make it more challenging to get on the shelves or even some libraries and schools. That the two issues are inextricably woven together in this story shows the complexity of these social issues, and what teens themselves have to face every single day as they navigate through their adolescence.

And, yes, there’s kissing and talk about sex – it seems it wouldn’t be a Harlequin without it. But it’s teen appropriate, exploring, and safe. Above all, the character of Chelsea carries this story through the growth and development of her character. Her silence allows her to finally get to know herself and to develop who she wants herself to be without shadowing others. She gets smarter as the story progresses (enjoying math problems and actually finishing reading assignments), but also wiser about her past and what she no longer wants to be. She is ready to face a future of uncertainty, but a much brighter and more hopeful future as she continues to discover who she is.