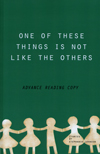

“I try to name the thing we never missed until it was lost, all the things that never stood a chance in this beautiful world.” So ends “My Neighbor Doesn’t Remember Everything She Forgets” from Stephanie Johnson’s debut One of These Things Is Not Like the Others, and it may well serve as a capsule of its concerns: to carefully observe life’s vicissitudes, to spotlight minutiae, to bear witness. The book is filled with internal squalls and domestic squabbles. In story after story, scene after scene, there is Johnson’s unwavering focus, and you can almost see her sharpening her senses.

“I try to name the thing we never missed until it was lost, all the things that never stood a chance in this beautiful world.” So ends “My Neighbor Doesn’t Remember Everything She Forgets” from Stephanie Johnson’s debut One of These Things Is Not Like the Others, and it may well serve as a capsule of its concerns: to carefully observe life’s vicissitudes, to spotlight minutiae, to bear witness. The book is filled with internal squalls and domestic squabbles. In story after story, scene after scene, there is Johnson’s unwavering focus, and you can almost see her sharpening her senses.

These are abandoned characters, who often turn the radio dial for some solace, some escape. We find one “singing along with country heartbreak songs” needing “ten more years of haphazardly packed baggage to know he was too afraid of loneliness to ever go for good,” doing whatever he or she can to just hold on. They are caught in between like the “other woman” who doesn’t “know which one of [them] has fallen in the water, which one of [them] is struggling to shore.” In “My Cousin Billy Is Dismantled,” Billy returns from Vietnam “disguised in darkness. Home in one piece but no longer at home anywhere.” Billy avoids his family and they give him the space he needs while they hope for some restoration. Rhoda, a friend, arriving “like an uninvited Godsend,” takes apart his truck’s engine until he rushes outside. Reading this story, I was reminded of Ben Harper’s song “Keep It Together (So I Can Fall Apart)” especially reading how Billy handed Rhoda “fallen pieces, the broken things he desperately needed her to put back together.” This climactic moment is almost literally wrenching.

One of Johnson’s most powerful stories is “Thesmophoria.” As one of the collection’s longer stories it makes me wonder what Johnson would do in a novel. Here she builds a whole world filled with physicality, sensual detail, and emotional grit. Besides the title (referring to the festival honoring the goddesses Demeter and Persephone), the story has other Greek references including a character’s name, “Lex,” meaning word, law, and reading, as well as various myths like Pandora’s Box, and the narrator, once she’s lost Lex—her word, as it were—finds solace in words, and especially in reading “Greek Philosophy and Classical Mythology.” Other references strikingly abound, all without distracting the reader, or disturbing the story’s onward flow.

It begins with Lex questioning “whether the world continued once his eyes closed,” asking the narrator to imagine “‘you’re like a TV. When I close my eyes, it’s like pushing the power button. Your programming might still be there, but it doesn’t really exist unless I’m watching it.” It’s a variation of the familiar question, “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around, does it make a sound?” This theme of immateriality is carried throughout the story as Lex, who, after an initial infatuation, sees “through the woman he invented . . . and never seemed to like who these woman were when they were out of his sight.” Later, discovering that Lex is leaving for good, the narrator feels (echoing this out of sight, out of mind idea) “like a television with a blown picture tube.” And when he returns, she “felt as if [she] were everywhere and nowhere, as though with a sudden pop and fizz a picture had filled a dark television screen.” Meditating on this idea once again, she “believed there was a world outside what [she’d] seen because Lex was now out of sight, yet still existing someplace I couldn’t touch because I hadn’t been there.”

But “Thesmophoria” isn’t merely a vehicle for philosophical inquiry but an emotionally moving story with stunning passages like this one:

Many times, I would lie in bed at night and think about where Lex had gone. I’d imagine the frame of his bones, each one a line on a map taking him closer towards what he was looking for and farther away from the land I knew instinctively and never needed a map to guide me through. I imagined it would have been the same way with Lex. Had we been lovers, I would have instinctively known his twists and turns and the little bumps of his spine, small foothills off the flat lands of his flesh. At that time, I believed a person could walk forever on those railroad tie bumps, a cross-country journey from the base of his neck to the small of his back, and just like America, no matter how much you traveled, you could never see all there was to see.

Later, she realizes that “heartbreak could be written across one’s face like footprints in fresh snow” and then “how disappointment could be telegraphed through wrinkled lines on a face.” And while a woman in “Dirty Laundromat” “memorized” her mother’s unpainted face: “[w]rinkles and dots, a map leading nowhere,” these twenty-one stories lead to a number of somewheres; they are a kind of cartography of human frailty, of abandonment and duplicity, of yearning and desperation, of hope and joy. Like the narrator in “Thesmophoria,” these stories are “built of hard work and wisdom that comes from seeing things as they are and seeing things how they could be if everything turned out all right.” Open this book and find a guide for unforgettable journeys.