For there is something to be said for the even spacing of certain

kinds of structures.

For it is important to love the spaces in between—Remember the

interstitial bins and shapes that accommodate.

– “Jubilate: Burden, Kansas”

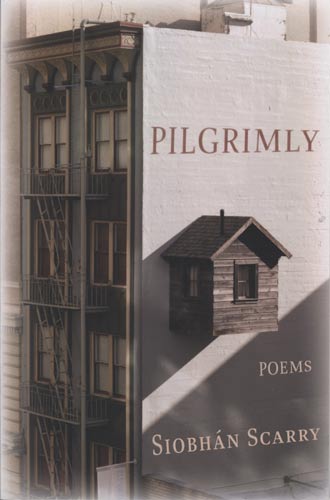

I admit, it wasn’t until I came across the above lines, 20 pages into the book, that I began to feel some affinity for Siobhan Scarry’s poetry.

For there is something to be said for the even spacing of certain

kinds of structures.

For it is important to love the spaces in between—Remember the

interstitial bins and shapes that accommodate.

– “Jubilate: Burden, Kansas”

I admit, it wasn’t until I came across the above lines, 20 pages into the book, that I began to feel some affinity for Siobhan Scarry’s poetry. Scarry’s language is dense—so dense that, as I read, I often felt I was slogging through linguistic quagmire. But then there are simplistic lines like these with words such as “interstitial” that sent shivers up and down my spine. These lines demanded a response: Oddly enough, the poetry, shaped into wordy squares and rectangles, rarely makes way for spaces; yet, that seems to be precisely the point. When our lives are squeezed so tightly, formed by the density of circumstance and relationships, we are forced to seek air and light in the most miniscule pores between things—in the folds of a lover’s body, the play between sunrays, the metallic beauty of silos and other steel structures otherwise disregarded in a landscape. We are forced to slow down and intentionally travel surfaces, explore situations, contemplate people, rediscover worth that has been long obscured by “teeming agar: circuitry of atomic life, germs in the palimpsestic rigor” (“Living Room”).

“How surely we twine,” the poem continues, “our idiot secrets into a knotted thing that tugs the root of each heart clear of its chest.” In other words, our worlds really are quagmire when weighted with dishonesty, rumors, distrust, mundane happenings, etc., and it is everyday wonderment that releases us from “the work of obligation” so that we can “love the spaces” (“Jubilate: Burden, Kansas”) again, look for opportunities to say nothing, enjoy simplicity, trust.

Personally, I prefer short, concise poetry so, as a reader, I struggled with Scarry’s poems because they insist I read slowly and contemplate the movement and meaning in every single line. But, the book is called Pilgrimy, and I’m beginning to realize that I live my life hastily. Scarry is waking me up to the fact that I have forgotten the feel of the “(s)mooth stump of the gone tree, dark hole in the center, starburst splintering outward” (“Three Trees”) and how to unburden by drawing “maps. [ . . . ] on the arms after sunlight, white / run of roads intersecting, to be tasted at night when the body is tired / from rowing” (“Residue”) and it’s been a long time since I’ve noticed “how the sculptor’s hands shook when he saw this day: sap bubbling up, cracking open the wooden skin of his women’s arms, running down, thick and alive, sharp smell of” (“Dream of the Moving Image”). Scarry has stopped me short of inhaling, ready to exhale. I want to suspend living for an eternity so that I can really learn to live.

There’s something in this poetic journey that has begun to seduce me and, on second reading, I’m feeling less “quagmired,” more baptized. I’m washing in “each / crunched footprint, a shallow pool of water cupped, collecting bits of winter sky” (“Littoral”). Every pool leading me “(t)o grow into something molded by other means” until “I am salt-scrimmed, basalted, spooned” (“Hieratic”). I only need “(f)ollow the map of black tarmac cracks, rifts like riverbed, running for miles” (“Nine Threads”). And I will “learn what can come of breakage, to hear again the loud humming” (“The Return”).

This book is for the pilgrim, the individual willing to migrate and ruminate. It deserves to be read day by day, one poem at a time, like a devotional. I will certainly read it again that way, hoping to learn more about “the vestigial parts of the self” (“Hieratic”). After all, says the same poem, “(a) self is such temporal plastic and can be molded to serve a million gods.” Best to be steady and intentional with our lives and the living things around us. Best to pay attention to “the marks our walking makes, words scraped onto the slow backs of turtles” for “(h)ow surely it moves beneath us, scriptura continua, our illegible lives” (“Attempts at Divination”).

Dear pilgrim, you will LOVE these poems.