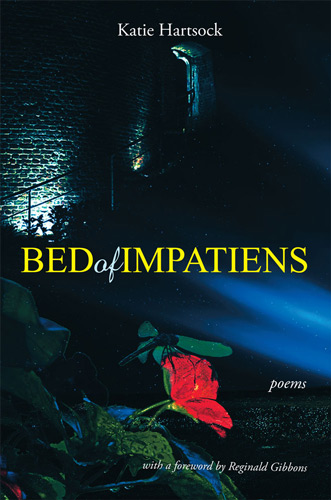

Bed of Impatiens

Katie Hartsock’s debut full-length collection of poems is a sprightly and sophisticated exploration of its title: Bed of Impatiens. Most probably know impatiens as a species of flowering plant, which, according to some 18th Century botanists, the flower is so named because its capsules readily burst open when touched. However, it also shares the same Latin root for the word “impatient” which has other definitions, including “eagerly desirous” and “not being able to endure.” Hartsock’s book has very little to do with a literal bed of flowers, but rather more to do with lying down in a bed of various desires that requires or inspires a restless (and lyrically fruitful) impatience.

Katie Hartsock’s debut full-length collection of poems is a sprightly and sophisticated exploration of its title: Bed of Impatiens. Most probably know impatiens as a species of flowering plant, which, according to some 18th Century botanists, the flower is so named because its capsules readily burst open when touched. However, it also shares the same Latin root for the word “impatient” which has other definitions, including “eagerly desirous” and “not being able to endure.” Hartsock’s book has very little to do with a literal bed of flowers, but rather more to do with lying down in a bed of various desires that requires or inspires a restless (and lyrically fruitful) impatience.

The book is divided into three sections. The first, “Wild Papyri,” contains the poem “Mississippi Stasimon,” which declares: “There’s no nostalgia/a river can’t bring and bear away.” And the entire first section of the book is quite river-like indeed: meandering through a large variety of classical/mythological topics and figures including Medea, the Fates, and the Myrmidons (legendary Greeks who fought in the Trojan War and were said to have been created by Zeus from a colony of ants). There is also a wonderfully inventive poem about an imaginary sister of Dostoevsky’s Karamazov brothers that begins:

All things that occur in fours

have a fifth, a conspirator

unbeknownst to the conspiracy,

and ignored by the narrator.

A bastard season of a sister

who borrows the defining features

of her brothers: the cynic,

the sensualist, the wretch,

the mystic. Without her,

they cannot become each other.

(That line, “A bastard season of a sister” would make a great title for a punk rock album.)

Part two of the book is titled “Hotels, Motels, and Extended Stays.” This section is full of impatient beds (the kind of beds you actually try to sleep on) in what author Linda Gregerson calls a “drop-dead formally exhilarating sequence” on the back cover of the book. We learn in some of these poems that “What doesn’t kill you / might kill you any day now” and that “The problem with waiting for the answer / is the answer/ has been waiting longer.” One of my favorite poems in the book occurs in this second section, “The Ducks on a Whiskey River Motel”:

Who knows how deep they plunge

or long they dive, what crumbs they find,

how much is enough to resurface. Hard billed,

tough-as-rusty-nails willed, they kick

and keep kicking all the way down.

Note the internal rhyme in the poem above: plunge and crumbs, billed and willed. Like most authors who publish through Able Muse Press, Hartsock knows her poetic forms, her meters, and is a skillful user of rhyme.

The final section of the book deals with St. Augustine and his Confessions. These poems are written from a more personal/first person point of view, struggling (impatiently of course) with faith and faithlessness. In “Augustine XII,” God is addressed directly as: “you, a mosaic of meanings, / of differing truths that do not undo / each other.” That is also as good a description as any of Hartsock’s accomplishments in this book. She has pieced together a glittering mosaic of poems mostly characterized by a natural free verse cadence, but there are more “formalish” elements as well; for example, the poem “Cuticles” is a sonnet ending with the couplet: “The trees, their wild unrolling limbs all draped in white, / offer up fingers which they have no teeth to bite.”

Despite the wide-ranging subject matter of the poems (and the book does feel a bit like it is easily three separate chapbooks in one volume), Hartsock’s poetic voice is consistently in command of the material throughout. Many thanks to Able Muse for introducing readers to this richly textured and extravagant bed of verses. I expect that we will be seeing much more from Katie Hartsock in the future.