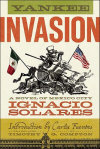

Yankee Invasion

For those readers drawn to history and psychology, Solares’s Yankee Invasion is a novel certain to intrigue. Set in the aftermath of the Mexican-American war of 1846-48, the novel is narrated by Abelardo, who struggles to write an account of the recent war even while he is still dominated by the mental trauma of the conflict.

For those readers drawn to history and psychology, Solares’s Yankee Invasion is a novel certain to intrigue. Set in the aftermath of the Mexican-American war of 1846-48, the novel is narrated by Abelardo, who struggles to write an account of the recent war even while he is still dominated by the mental trauma of the conflict.

As Carlos Fuentes, who introduces the novel, notes, Solares writes “from the precarious point of the future immediate to the novel.” This position is, indeed, precarious, for Abelardo veers in and out of his past, flashing from the present of writing his narrative, to the events before and during the war. Time is fluid and fast-changing, or as the narrator puts it: “time seemed to be doing continual somersaults.” Readers might find this effect rather disconcerting, but Solares makes it rewarding as well. While he struggles to separate past from present and to organize his memory into a sensible story, Abelardo finds himself in “a situation that could swallow up the present and the future, like the sea swallows up shipwreck victims.” These reflections make it apparent that time itself is one of the major themes of the novel. Even as the characters note, we “can only understand reality from the point of view we find ourselves in at the moment,” so too the reader must slip into the timestream of the novel and not worry too much about what is past and what is present.

For all that the novel does move around, it is also anchored in history. Some of the richest parts of the story come during the moments of attack, when the American army closes in on Mexico City. At the heart of the novel, as the memory moves closer and closer to the decisive instant, the narrative focuses on a section of the Mexican Army holding position in a convent. The action is tense and peppered with winning details: “Their ammunition runs out and so they turn to the supplies sent to them by Santa Anna, but they find it is all nineteen-weight ammunition, a caliber far bigger than the fifteen-weight bullets which they need. The cartridges do not begin to fit in their arms.” The utter futility, the looming defeat, is made more wrenching by the nuanced recounting of such scenes.

Of course, it is possible to have too much of a good thing, and for this reader, sections of Solares’s novel were impenetrable thickets of Mexican political history. In a chapter that reads more like pages from a history textbook than a work of literature, the reader is berated with the biography of Santa Anna; the exposition recounts that the leader “ended up at odds with the federalists, the centrists, the clergy, the poor, the working class, government employees and capitalists (from whom he was constantly demanding money). For example, he fired all government employees who did not adhere to the Jalisco Plan and the Principles of Tacubaya – triggering an unprecedented rate of unemployment.” As history textbooks go, the material is compelling, but for a novel, it can create some difficult and tedious sections.

However, if one wades through the history, there are charming insights that make the effort worthwhile. For instance, a friend of the narrator’s contemplating the changes wrought by the recent war reflects on Mexico’s new borders: “Without Texas, our country will have the shape of a horn of plenty…except that the opening of the horn faces the United States!” Witty observations, many of them with intriguing possibilities of contemporary meaning, abound.

Richest though, are Solares’s observations about humankind and psychology. As poor Abelardo tries to make sense of what has happened to him, he muses that “perhaps things actually aren’t the way we live them but the way we remember them.” No line comes closer to summing up the nature of this text. In essence, Solares’ novel is a novel of remembering, or memory as an act of creation. Dense and complex, this is not a volume to be read lightly.