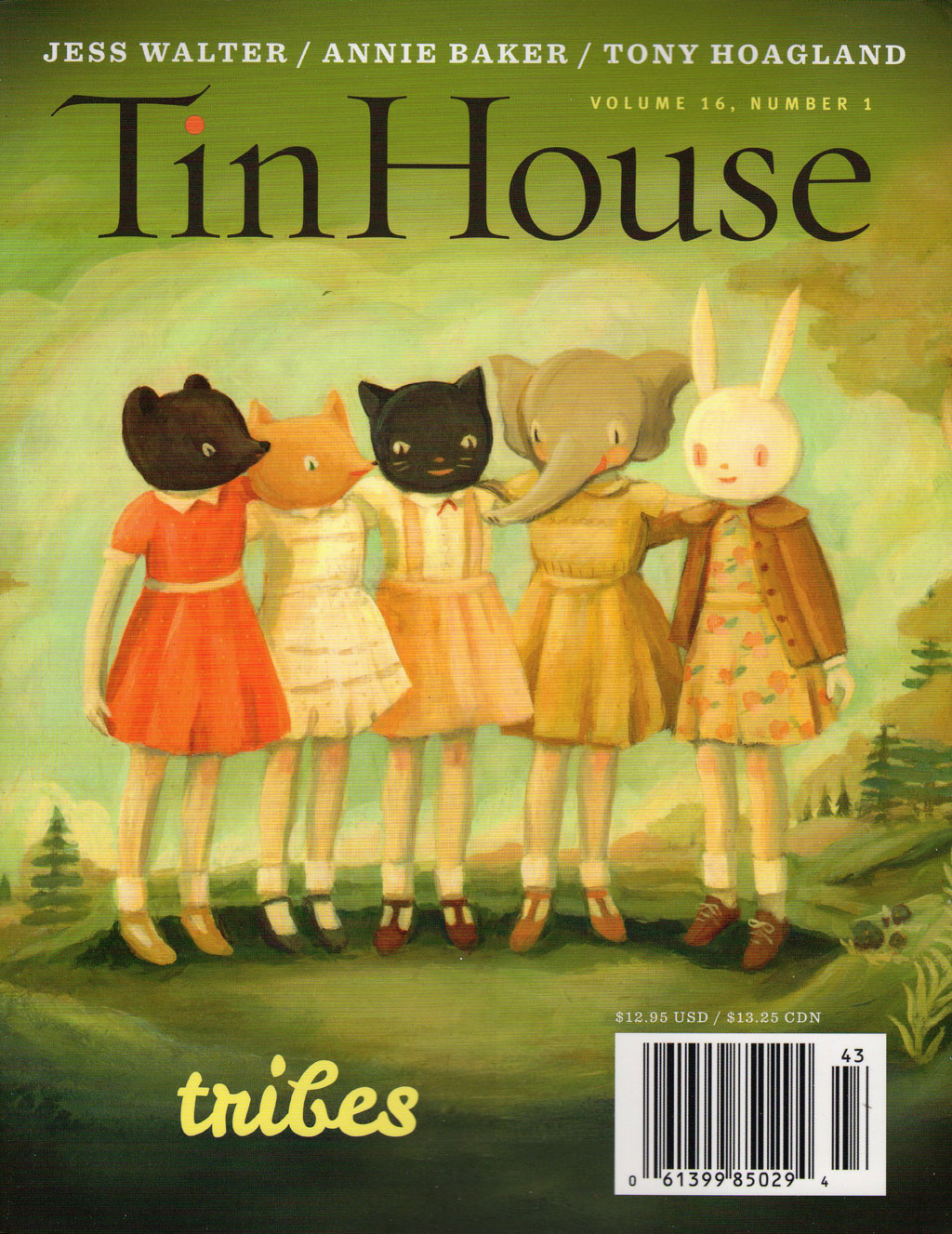

Tin House – Fall 2014

For their latest issue, the editors of Tin House have gone tribal, calling on some of their “favorite storytellers and poets” to help explain “what life is like in our contemporary tribes.” In creating their “Tribes” issue, they’ve assembled a trenchant and soulful collection of poetry, fiction, and essays that unsettle as they entertain, exploring the consolation and alienation of belonging or wanting to belong. Poetry from Tony Hoagland and Cate Marvin, fiction from Jess Walter and Julia Elliott, essays from Roxanne Gay and Molly Ringwald, as well as the work of many other well-known writers, all share communal space in this lively gathering of the literary tribes.

For their latest issue, the editors of Tin House have gone tribal, calling on some of their “favorite storytellers and poets” to help explain “what life is like in our contemporary tribes.” In creating their “Tribes” issue, they’ve assembled a trenchant and soulful collection of poetry, fiction, and essays that unsettle as they entertain, exploring the consolation and alienation of belonging or wanting to belong. Poetry from Tony Hoagland and Cate Marvin, fiction from Jess Walter and Julia Elliott, essays from Roxanne Gay and Molly Ringwald, as well as the work of many other well-known writers, all share communal space in this lively gathering of the literary tribes.

Poets Tony Hoagland and Cate Marvin both contribute gripping poems that explore unseemly aspects of sexuality and gender, describing the tacit behavioral norms of their respective tribes.

Hoagland’s “The Roman Empire” shows that even a seemingly innocuous activity like a walk in the park can be freighted with dark sexual tension as the male speaker in the poem passes a lady in the park who obeys unspoken rules of interaction, keeping her distance and averting her eyes. Hoagland’s decision to put the poem in first person makes the reader privy to the man’s rather self-aware and rational mind, providing insight into his character that the passing woman doesn’t have. This choice, combined with Hoagland’s witty, matter-of-fact diction, highlights the tension between ordinary interaction and potential violence:

A visitor from outer space, observing us

From some hidden vantage placeWould guess at some terrible historical event

Of which our politeness is the evidence—The man, attempting to look harmless;

The woman trying not to seem afraid.Look at that dogwood tree flowering nearby, with a bird in it.

After you. No, after you.

In Marvin’s three-part poem “Chilly Voice in the Tropics,,” a woman clinically catalogues the reasons compelling her to remain in a relationship with a man while being fully aware of the extent of his habitual unfaithfulness. An uneasy sorority is created as the speaker shows an intuitive understanding of the other women’s plights, even as she acknowledges the competition that exists between them:

. . . She’s so inconsequential, has

no idea she’s being undone. You’d think she’s dumb, butshe’s merely being deceived, we both have lain on the same

sheets, proffered lips to the same mouth, willingly handed

ourselves over as if our soul-stuff were some dumb oyster

worthy of any mouth: an eroticism. . . .

With its long lines, subdued internal rhymes, and icily deliberate tone, the poem reads almost like a detective story where the mystery feels destined to remain unsolved.

Julia Elliott takes the issue’s theme in a slightly more literal direction with her short story “Caveman Diet,” narrated by Ellen Wiggins, a long-engaged woman looking to escape her fiancé’s ennui and shed a few pounds by traveling to “Pleisto-Scene Island, the Paleopalooza of fitness adventure tourism.” Run by a stone-age Tony Robbins-type guru who goes by the name of Zugnord, the resort is equal parts survivalist camp, theme park, and singles mixer, where reversion to a more primitive state proves seductive. Elliott’s hilariously apt characterization and eye for drawing connections between the primitive and the modern gives her high-concept story its verve. This talent is on full display in the comic bit of characterization which greets her fiancé’s surprise arrival at the resort: “He’s wearing khakis, a vintage plaid shirt, these mouthwash-green dead-stock 1980s Pumas he spent two weeks stalking on Etsy. He looks smaller, as though the journey has deflated him and he needs a pump of air.”

In his first-person short story, “Mr. Voice,” Jess Walter shows why heredity isn’t always the most important factor determining who we decide to call family. In the story, Tonya, a mother of two college-age daughters, reflects on her own experience as a daughter burdened by the expectations and assumptions that came from inheriting her mother’s good looks. Tonya’s mother, after dating a string of men in her early thirties, decides to cash in on her good looks, settling down with Mr. Voice, a local radio and television personality almost twenty years her senior. While the marriage provides lasting stability for Tonya, that stability comes from unexpected sources after her mother’s restless spirit proves incapable of being satisfied by domestic life. Walter’s narrative resonates because of his ability to make the shifting allegiances of family life seem like natural extensions of each character’s personality and history.

Per usual, the latest issue of Tin House also features an eye-opening collection of book reviews in which neglected classics and cult favorites are discussed. Reviews of books by Eve Babitz, Frank Stanford, and Thomas Klise, among others, are sure to expose even the bookwormiest reader of the “Tribes” issue to an overlooked gem or two.

[www.tinhouse.com]