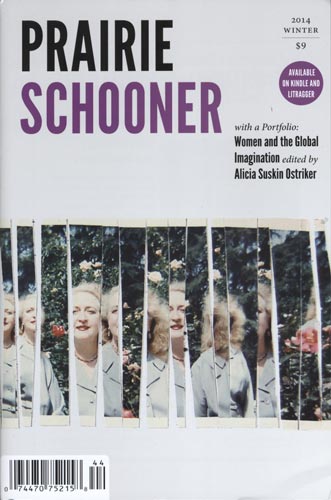

Prairie Schooner – Winter 2014

Without question, Prairie Schooner is one of the top American literary magazines, as measured by quality, presentation, and longevity. It began in 1926, and it continues as a print quarterly and online blog at the University of Nebraska, in Lincoln. Poet Kwame Dawes is editor-in-chief, and the magazine has a staff of 47 assistant editors, editorial assistants, and alumni readers. A well-established publication indeed. The current issue musters an impressive roster of contributors, most with advanced degrees, publications, awards, and residencies. More than a few teach writing at a college or university. Without question, Prairie Schooner is one of the top American literary magazines, as measured by quality, presentation, and longevity. It began in 1926, and it continues as a print quarterly and online blog at the University of Nebraska, in Lincoln. Poet Kwame Dawes is editor-in-chief, and the magazine has a staff of 47 assistant editors, editorial assistants, and alumni readers. A well-established publication indeed. The current issue musters an impressive roster of contributors, most with advanced degrees, publications, awards, and residencies. More than a few teach writing at a college or university.

About one third of the current issue is devoted to the portfolio “Women and the Global Imagination,” which consists of 32 women poets, with one or two poems from each. They come from all over the globe and from many walks of life. Alicia Ostriker, the poet who arranged the portfolio, says in her preface: “There is no narrowly defined female aesthetic here. The poems are lyric, satiric, mythic, experimental, surreal, expansive, laconic, conversational, tender, angry, allegorical, oracular.”

And so they are. They include two translations from the French by Marilyn Hacker of poems by Vénus Khoury-Ghata, other translations, and a “Hymn to Aphrodite” by Ursula K. Le Guin, with reference to Fukushima. Other poems included focus on a girl who runs away from home in Guatemala, fugitive slaves in nineteenth-century America, and harsh conditions in Gaza and Havana today. There are phrases in foreign languages, footnotes to help the reader understand, references to sexual organs, and sentimental imagery. The painful emotions and injustices in these poems make for difficult, but necessary, reading.

John Kinsella has a five-page poem called “Electric Rococo Recollections of Jam Tree Gully from Afar,” from his new volume Jam Tree Gully, which includes images of harpsichord music, coal smoke, leaves in the gutter, and a “radioactive spill.” Rafael Campo has two poems that grow out of his experience as a physician: “The doctor may reserve the right to do / some harm. He may not pray for you.” John L. Stanizzi shows us a boy who never speaks and who draws “super-monsters / with his black pen / [. . .] all muscle and detail and weaponry.” Heather Sellers invites us to “Lunch in Three Realms,” which begins: “I press the two cold slices / of bread to my cheeks. La!”

The seven stories and one essay put more in the sandwich. In “Another Man’s Treasure” by Dave Madden, a garbage collector takes us on his route. We get the bad smells and bizarre habits of people “who did not bother to secure their bags of refuse,” along with a white-trash wife and the murder of a transgender boy.

Baird Harper gives us another first-person story, “When a Child in Your Town Goes Missing,” which features a hit-and-run accident in the suburbs, two men hiking in Peru, and an inept group of Marxist kidnappers. It is dark and painful—foot blisters, hunger, freezing nights in a tent, kidney stones—and yet, funny.

Laina Mullin Pruett lets a thirteen-year old boy tell his story in “Telling the Bees.” An elderly beekeeper neighbor dies, and the boy decides that he must care for the bees in their backyard hive. When the man’s adult son and teenage granddaughter arrive, the boy and girl go swimming and taste their first love. It’s sweet and utterly realistic.

Stories by Charles Lowe and Ron Riekki are written in a jerky style that suits the subject matter. Lowe’s story shows a Chinese woman married to an American graduate student she calls “the book idiot.” She cooks aggressively in the kitchen as he talks to students in the living room of their low-rent apartment. Riekki gives us the perspective of a young paramedic or EMT as he deals with a car crash—one dead, one badly hurt.

Prairie Schooner provides a lot to process in this issue, from the “Women and the Global Imagination” portfolio to the poetry. Despite the wide variety of subject matter in this issue’s stories, a common connection can be made: The fictional body count is high. But the pleasures are real.

[prairieschooner.unl.edu]