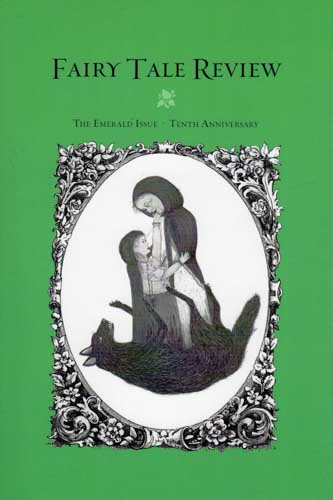

Fairy Tale Review – 2014

Fairy Tale Review maintains its fanciful theme well, but its significance as a literary document exceeds whimsy: the authors transform modern literature, spackling any clichés or invention with language, philosophy, and critical energy. Fairy Tale Review maintains its fanciful theme well, but its significance as a literary document exceeds whimsy: the authors transform modern literature, spackling any clichés or invention with language, philosophy, and critical energy.

The theme for this issue is Oz. As editor Timothy Schaffert quotes L. Frank Baum, “modern tales don’t require a moral.” One might suggest “of course they do, old sport” and go on reading, but Baum may have been referring to morals as a form of value propaganda, and in this honorary issue we see none of that, but we do see strong ideas, rich with significance—and morals.

Take, for example, Christopher Barzak’s “Dorothy, Rising.” The clear voice, the expert storytelling, and the arrangement and pacing of ideas are as magical as any emerald city of words. Barzak spins his moral toward the end: this story is not immune to time. Rather, we see a glimpse of the future Dorothy, the independent almost satirical (chick lit) portrayal of the heroine. Somewhere behind her dolled-up ‘do, looms the specter of foreclosure. And you don’t feel that tension in chick-lit, the idea of the economics behind everything, a shack bearing all the weight of an invisible hand.

Nicely paired Jaydn DeWald’s “American Fairy Tale” with Cate Fricke’s “Tin Girl” modernize Oz again. DeWald’s prose is fine music, one that weaves in Oz compliantly but also provides the following:

Tap your Adidas together & wake up in Z’s tenement again, mid-to-late autumn, San Francisco, 2007, staring up at a storm-gray staircase . . . sweeping ever upward into blackness, into a little skylight of night, like a twister—

It is a cold song—and lovely—to see DeWald marry opposites against a backdrop of strong, unifying emotion. On the facing page is Cate Fricke’s “Tin Girl,” which seems reasonably realistic at first, and then, ever so gracefully, weaves in surrealism that solves the narrator’s problem while creating a secondary problem—the idea of age and femininity, the pillage of our mothers for the service of men. You might perceive a post-war widow in her pillbox and “smart Sunday heels,” but Fricke does not end there. The reader realizes the ticking of time with each rocking chair creak, the brevity of beauty, the strong thief’s calves deriving all power from precarious youth.

Stephanie Nash’s “After the Wind” references Oz, but her reach is broad enough to eke out a conclusion for Baum’s 1904 tale. It represents a dream for every damaged beauty—the idea that a nervous, somewhat ostracized farm girl marries the town doctor, who loves her and gives her a legion of children. It is told like a fairy tale, too, with very little departure from the driving narrative. In the fragility of the protagonist, the reader seeks the modern preoccupation—that one’s suffering is ancient and redeemable.

Daniel A. Olivas’s “The Last Dream of Pánfilo Velasco” functions on many levels. For example, a straight read might reveal nods to magic realism as a mystical narration of the concept of love and loyalty complete with successful incorporation of Dante and other magical references. One feels the shadow of that cannon. But a closer read might develop appreciation for the fine-tuned absurdity of the tale. On read two, I was laughing, completely engrossed with the wildness of Olivas’s imagination.

Olivas may not be alone in alluding to the magic realism movement. Lindsay Stern’s “The Great Forgetting” masterfully invokes Saramago’s Blindness but names the plague to be one of time, not personal affliction. Here is her first paragraph:

On an autumn morning in Year 20, the people of Lüz awoke to find Memory reversed. Recollections of the day to come wafted into their conversation, their morning jokes. History loomed, swept images. The future, meanwhile, fell into view.

Stern maintains the clip and the challenge, creating a supersonic setting that fulfils the promise of that introductory paragraph.

The best opening sentence in America at this moment starts the story “Paint Chips” by Gabriel Thibodeau: “I want to kill my father but know my mother will miss him, so I turn him to stone and put him in the garden.” Thibodeau is faithful to the emotional storyline, but the wry delivery makes the narrator’s surreal capabilities wonderfully funny. And he does maximize the beauty of it: “If I had a brush, I would bring it to her face and paint the sea.”

Daniel Olivas describes the magic of this magazine best—from the approach of a fairy tale to the chance to present new incantations of the magic realism canon: “No matter what we call it, I find this type of storytelling quite liberating.” As a reader, I nod. What lively dreams. How wonderfully spun. How essential to the canon and beyond.

[digitalcommons.wayne.edu/fairytalereview]