Consequence – Spring 2016

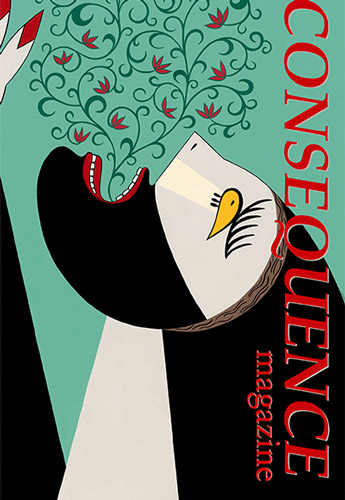

American Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman once said, “War is Hell,” but Consequence magazine takes the hellish landscape of war and transforms it into inspiring works of art, fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Consequence is “an international literary magazine published annually, focusing on the culture and consequences of war.” The cover art of the current volume of Consequence exhibits this goal in a powerful illustration of life and beauty rising up from a mouth of suffering alluding to Picasso’s Guernica.

American Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman once said, “War is Hell,” but Consequence magazine takes the hellish landscape of war and transforms it into inspiring works of art, fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Consequence is “an international literary magazine published annually, focusing on the culture and consequences of war.” The cover art of the current volume of Consequence exhibits this goal in a powerful illustration of life and beauty rising up from a mouth of suffering alluding to Picasso’s Guernica.

The special feature of this issue is a collection of Israeli and Palestinian writers who write different perspectives on the conflict between these two peoples. My two favorite pieces from this collection are “War on Tel Aviv!” by Rajaa Natour and “Conflict Zone Date” by Khulud Khamis. Natour’s piece of nonfiction, translated from Arabic by Julie Yelle, is a reflection of the author’s memory of rocket attacks by Hamas in Tel Aviv:

After that day, I began—if the siren went off while I was putting on my eyeliner—to hold fast to my eyeliner pencil, extend the eyeliner across my eyelid, and say that a woman beautifies herself under death, in death, and before blood! I began to fear forgetting that I’m here, that I haven’t died, and that they haven’t yet taken everything. If it went off while I was smoking, I lit another cigarette with the light of the first and said, “Oh, why doesn’t Tel Aviv just burn up like Gaza is burning up and take Jaffa along with it!”

The author’s stream-of-consciousness style of writing pulls readers into the Gaza strip and illustrates her anger and frustration against the brutality and absurdity of the centuries-old conflict. Not all the writing is gloomy in this issue, though. Khamis’s fiction “Conflict Zone Date” is a humorous story about a Palestinian man and an Israeli woman who take a chance to start a relationship in one of the most violent places of the Middle East. Saleh, who works with Maya at the same company, knows how hard it would be for them to be together, but still builds up the courage to ask her out on a date:

“I’m good,” Saleh now looks Maya in the eye, with a shy smile on his face. “Was just thinking, you know, that company party this weekend . . . would you . . . I mean . . . I was thinking of going . . . maybe . . . and . . . ” Maya waits for the rest of his sentence, holding back her smile. Saleh takes a sip of his water, steadies his hands on his legs. “Ok, here’s the thing. Would you like to come with me to the party? There, I said it. Now you can shoot me.”

Their date does not go without any conflict, though, as their growing relationship becomes known by their parents and others who disapprove. This story contains a good balance of humor and tension, which also serves as a counterpoint to the more serious works contained within this journal.

My favorite poems in this issue are “Take Only What is Most Important” by Serhiy Zhadan and “Fried Pork Skins” by Teresa Mei Chuc. Zhadan’s poem, translated from the Ukrainian by Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps, shows the desperation of war refugees fleeing their homes:

Take only what is most important. Take the letters.

Take only what you can carry.

Take the icons and the embroidery, take the silver,

Take the wooden crucifix and the golden replicas

Chuc’s poem, with the subtitle of “A Gift to Her Husband in a Vietcong Reeducation Camp,” shows us a prisoner of war receiving a rare gift from home:

He opened the package slowly, carefully, quietly, making sure no

one heard the wax paper

unfolding in the night.

With the wrapped gift from his wife in his hands, he lay.

He ate the entire package of fried pork skins by himself in a room

without light.

What I enjoy so much about both of these poems is how well each poet writes about how the horrors of war disrupt everyday life, turning people into refugees or prisoners. However, these poets also show us how common people defy the disruptive nature of war and commit to survive and hold on to their humanity.

The writers mentioned are only a small sampling of the 200 pages of literature in this volume. This issue of Consequence may cause discomfort as it transports readers to conflict zones around the world and shows them the depravity of war, but therein is also our shared humanity on display through powerful writing.

[www.consequencemagazine.org]