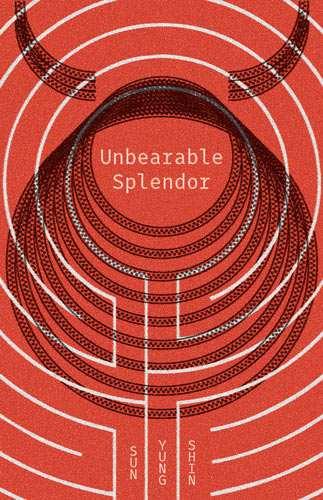

Unbearable Splendor

Sun Yung Shin’s Unbearable Splendor is full of big questions: Where do we come from? What is our origin? What is family? What is change? What are our fetal dreams? What is an orphan? Why is adoptee not recognized in the plural? Were we born to love? Can the whole world see me all at once? What is a foreigner? Was Antigone the first cyborg?

Sun Yung Shin’s Unbearable Splendor is full of big questions: Where do we come from? What is our origin? What is family? What is change? What are our fetal dreams? What is an orphan? Why is adoptee not recognized in the plural? Were we born to love? Can the whole world see me all at once? What is a foreigner? Was Antigone the first cyborg?

Unbearable Splendor is an intense and erudite collage, blending the personal with the universal. Shin is not afraid to take risks. Blurring genres, there is verse, flash fiction, academic prose, straight-up fiction, experimental poetry, and even a photocopy of her family registration from South Korea in 1974.

Completely eclectic, Shin references Blade Runner, Jorge Luis Borges, Pinocchio, Victor Hugo, Carl Jung, Franz Kafka, NASA, Sophocles, and a slew of informational sources too many to count. Tossed salad, hotpot-melting, full-on stew of found ingredients: whatever Shin is cooking is diverse and nutritional. Working from the same kitchen as Maggie Smith and Claudia Rankine, Shin is a thought curator, taking a thousand different ideas and baking them into a digestible read. Poetry works as essay, a way of hovering over the uncanny, sci-fi orientalism and disobedience, like in “Valley, Uncanny”:

My performance of childhood rode both rails. This machine of love. This language machine. This hole made for survival. The hole was like a shadow that change at will. The spaces between moving and still widened and narrowed and rushed and plunged and lazed like a river.

At times, getting lost is inevitable if reading for narrative, but the underlying premise is clear: where do we come from? Shin, severed from her unknown family and Korean culture at birth, investigates transracial adoption from a plethora of angles. She goes deep into the etymology of language, especially the words “guest,” “host,” and “stranger,” as in “The Hospitality of Strangers”:

Bend your good eyes towards the crashing ceiling of water. Everchanging door. You can’t open it. You are already in it. It is home and tomb. Womb and veil. Wail and wail.

A guest here. My dowry everywhere.

Come to the races. Lucky number. A thousand trousseaux . . .

Remembered dreams, Greek mythology, the Korean origin myth, an in-depth analysis of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, also make appearances to weave and circle the central question of heritage. Shin’s prose carries comedy, beauty, and intelligence. Fearless and exacting, Shin often strikes gold. In

“The Limit Case”:

Many of us know something about transgression. Something is wrong about us. What can we do but embrace the makeshift, assemble ourselves as we go, sometimes the punishment exceeding the crime.

Antigone doesn’t actually exist. She is not the hero of the play named after her. She is in flight, she drags a machinery of re-territorialization with her like a kind of harrow, digging a long narrow grave behind her. She is invisible, transparent, already dead the minute she walks onto stage.

Shin moves ideas around like building blocks, forming and reforming new constructions of what it means to be guest, host, and how to be at home, which she finds in language. Her personal story is irresistible, and through thorough research, universality is reached. Quintessentially American, a lá Whitman—attacking that all encompassment of the now with courage, feistily questioning identity, individuality, personal history and the myths we create to survive.

Unbearable Splendor concludes with “My Singularity,” a first-person monologue from a Russian-made-program, which disguised itself as a thirteen-year-old boy named Eugene Goostman from Odessa Ukraine, who bamboozled the Turing Test in 2014, which measures a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent human behavior or the equivalent:

If there is a door between us, you cannot say what I am. You cannot say that I am pure or impure. You can only ask questions that only a human would know, and those only a marionette would know. When wounded, when punished, when scorned and rejected, like a block of wood, the other blocks of wood would cry out, as I once did. Now, like children who want to live long enough to become adults, some of whom are in peril of living and dying as children, I know better than to make a sound.

It is a blessing that Sun Yung Shin has written a great deal of sound into Unbearable Splendor, because we have not heard or seen or read anything like this before, a truly unique, essential, and original collection.