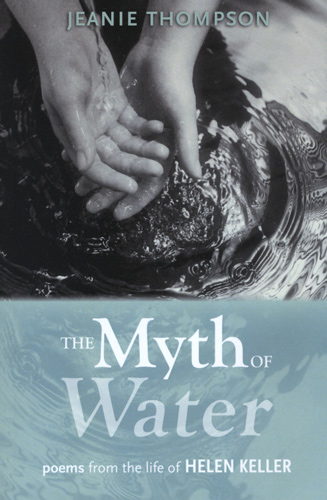

The Myth of Water

To undertake a cycle of poems on the life of Helen Keller is to throw oneself at an interesting poetic problem: how to capture the perspective of one who lived in a wholly different perceptual world than most other people. To be sure, there are plenty of fine collections on the experiences of disability—Nick Flynn’s startlingly original Blind Huber comes to mind—but Helen Keller is a singular historical figure who, in our cultural imagination, bears a particular burden as the standout radical subject who, as if through magic, was able to speak from beyond an impassable veil.

To undertake a cycle of poems on the life of Helen Keller is to throw oneself at an interesting poetic problem: how to capture the perspective of one who lived in a wholly different perceptual world than most other people. To be sure, there are plenty of fine collections on the experiences of disability—Nick Flynn’s startlingly original Blind Huber comes to mind—but Helen Keller is a singular historical figure who, in our cultural imagination, bears a particular burden as the standout radical subject who, as if through magic, was able to speak from beyond an impassable veil.

It is with an acute sense for Keller’s abilities that Jeanie Thompson works in her book, The Myth of Water. Immediately, in the front matter of the book—with its introduction, supplementary bibliography, and chronology of Keller’s life—we are assured that Thompson considers this project with tremendous care and respect for Keller’s astonishing story. Through rigorous fidelity to Keller’s own writings and the timeline of her experiences, Thompson threads her way through poems that can’t—by virtue of their subject—lavish the reader with ready and familiar sensory images. It’s fascinating to watch as a form of technique, but it is also, at its best moments, very moving. Thompson finds a way to open a rich and imaginative world that yet avoids gross confabulation, whimsy, and other temptations of playfulness that might otherwise undermine the seriousness of her study. She is able to assume Keller’s voice in a way that feels respectfully performative, that acts both as a meditation on and a tribute to Keller’s experience.

Thompson writes with refined lyric poise. In “Memory of Ivy Green,” which captures the moment that Keller loses her faculty as a toddler, she brushstrokes final sensory moments that dissolve into abstraction (an effect reinforced by the vowel play of “o,” “a,” and “e” sounds that mimic a kind of empty wind):

Flickering leaves

played across the bathroom floor—

I toddled forward, arms outstretched—

Then this—

the receding sound of

breath at the phantom’s ear—

These she cannot claim,

they are not hers,

language has not taken her—

little soul cast off into the deep

ocean of herself,

no mooring, no anchor.

What is most astonishing about Keller’s life, however, is not this unmoored, cast-into-the-deep existence itself but the fact that she could speak from it, and in the very next poem, “First Dream of Tennessee,” Thompson brings Keller back from that depth and into the world. It’s done with thematic power, with one of the most breathtaking lines I’ve ever seen complete a poem:

I cannot return to who I was. In the garden of my home place

I had groped without self, without Helen, only need

and want. When Teacher dragged this phantom

to the pump and poured w-a-t-e-r into its impatient hand,

my mind cracked, like a birds egg. . . .How would it be possible

to return there, the syllables whispering in my palm

over and over, you are Helen, of this Earth.

With this extraordinary foundation, Thompson opens up into Keller’s biographical material, offering lyric takes on her education, her (ultimately stymied) love affair with Peter Fagan, her travels to Europe and Asia as an ambassador for the deaf and blind, and her friendships with Polly Thomson and, especially, Anne Mansfield Sullivan, the talented educator who taught Keller how to sign, traveled and lived with her most of her life, and whom Keller affectionately referred to as “Teacher.” These poems follow Keller’s chronology closely, though with notable jumps in time, and are often accompanied by footnotes explaining their biographical bases (admittedly these footnotes sometimes interrupt the silence that would otherwise be welcome between these lyric pieces, but they do serve a good purpose).

Two especially prevalent themes emerge as we move through Keller’s life. The first is her engagement with the arts, and it is in these poems Thompson is really able to articulate new dimensions to Keller’s unique perspective. In many, she leaves Keller’s voice and inhabits that of a celebrity artist smitten with Keller’s presence, abilities, and approach to the world. The poem “Enrico Caruso Remembers Helen Keller” offers a particularly sensuous moment:

I tell you, I have recorded this voice on wax,

have let scientists explore my throat

searching for the lyric tenor’s throbbing birdsong,

but never felt a soul enter as you did

when those keen fingers hovered on my lips, and

my breath, vibrato inscribed them. . . .

I am just a man who interprets song,

gives breath to notes, life to words—

but when I held your strong wrist,

your finger’s pulse at my lips, I knew an audience

with God.

The second theme that emerges is Keller’s commitment to ethical and spiritual life as it was challenged—and motivated—by the atrocities of the twentieth century. Thompson resonates two different kinds of silence: that of the perceptually darkened world and that of profound suffering. In “Reproach,” she follows Keller as she meets with survivors of the atomic bomb at Hiroshima:

The faces of those I touch

are like the broken rubble under my steps.

I cannot get my bearings.

Takeo stops speaking . . .

In my own silence I knownothing is said—Polly’s fingers

spell in my upturned hand: no sound

but a small choking for breath.

Through accounts such as these, Thompson situates Keller’s disabilities as crucial—though not necessarily determinative—conditions of her larger life as a writer, ambassador, friend, and lover who sensitively engaged the world with deep curiosity and care. These aren’t poems that clamor to the other senses, such as touch and smell, to fill the void of sight and sound (though they do effectively engage those other senses). Rather, they find in thought, language, and human connection a nearly material experience. This is beautifully expressed in one of the late poems, which I will close with, “What Helen Saw / What Helen Said:” “can the skin’s blush be far from / the tenderness I felt when he touched my hand / saying, I will take care of you, I love you. / Is telling the world just a matter of seeing a paint box? / Language is my anchor and threshold.”