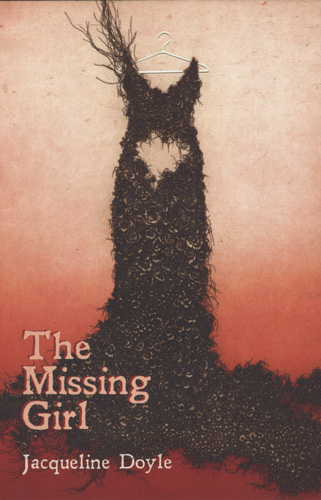

The Missing Girl

You soon may be the missing girl, you have taken the missing girl, you fantasize about the missing girl, you are the missing girl. In Jacqueline Doyle’s aptly-named The Missing Girl, we briefly take on all the roles before shucking the skin we’re in and donning a new one. Winner of the Black River Chapbook Competition through Black Lawrence Press, The Missing Girl draws us into the seedy darkness of everyday life in small bursts of haunting prose as Doyle forces us to consider being both the hunter and the hunted. Regardless of which position she leads us to, none is a comfortable role to be in.

You soon may be the missing girl, you have taken the missing girl, you fantasize about the missing girl, you are the missing girl. In Jacqueline Doyle’s aptly-named The Missing Girl, we briefly take on all the roles before shucking the skin we’re in and donning a new one. Winner of the Black River Chapbook Competition through Black Lawrence Press, The Missing Girl draws us into the seedy darkness of everyday life in small bursts of haunting prose as Doyle forces us to consider being both the hunter and the hunted. Regardless of which position she leads us to, none is a comfortable role to be in.

In the opening, titular story, Doyle immediately drops us into the darkness. Written in second-person, readers become the narrator. We see the signs for missing 14-year-old Eula Johnson. We read the stats for her appearance: height, weight, eye color and hair color, the clothes she was last seen wearing. Then suddenly we are fantasizing about being the person who took Eula. We are pulling our car over. We are talking to a young girl, calling her beautiful, trying to get her into the vehicle. We are becoming the hunter. But even in the position of the narrator, our thoughts are unreliable, a theme that carries throughout the chapbook. The unreliable narrator shows up repeatedly—do we believe everything or do we question everything, and when an accusation is made, do we take the side of the accused or the accuser?

In “You Never Know,” do we believe the narrator when he recounts a story of implied abduction to his airplane seatmate, or is he merely trying to get a rise out of the woman? Do we allow him to get a rise out of us as well? If we remain unaffected, maybe we don’t care about the little girl with him who’s “pulling on the handle to the [car] door, trying to get out.” He dangles the story in front of us, teasing and testing. The piece ends as the narrator gives his name to the woman beside him:

“I’m Herbert,” I say, though that’s not my name.

My driver’s license says Timothy. My wife calls me Tim. I can barely remember what my name was before that.

In this way, the narrator with this secret, hidden past can become any man. Herbert, Timothy, or Tim—it doesn’t matter. Each name is capable of the atrocious acts he alludes to.

“Something Like That,” takes readers in the other direction. This time, the survivor narrates, beginning:

I don’t know why I lied. Maybe it’s because someone finally believed me. So maybe it didn’t really happen in exactly that way with exactly those boys on exactly that night. I’m not sure anymore. But things have happened to me, on nights like that, with boys like that.

Again, we’re faced with an unreliable narrator who loops assault stories together until they’re blurred—until it’s hard to tell what really happened. This piece reminds me of the #MeToo campaign, friends’ and family members’ accounts of sexual assault blurring, so many similar stories being experienced and told. As the narrator of “Something Like That” attempts to piece together their story, it sounds so much like ones we may have heard or experienced ourselves, and we start mentally plugging in our own information. The piece ends:

So when the reporter was asking girls in my dorm for their stories, maybe I got confused, or maybe it all happened, and it’s just hard to remember, because why would I want to remember something like that, or tell a story like that, much less a lie like that?

The narrator admits she might not be telling the exact story—or maybe she is?—and our doubts end up mirroring the real-world victim-blaming women experience, and the instinct to question accusations of assault.

It is in this way that sometimes Doyle’s pieces are too real—too close to home. “Hula” sees an intoxicated woman taken advantage of in a bar, “My Blue Heaven” depicts a love affair gone terribly wrong, “The Victim” shows a little girl posing for a man with a camera, and “Let’s Play a Game” places readers in an alleyway beside a woman waking after a night of abuse. Open a news site or even your Facebook feed, and there is a good chance you’ll see a headline mirroring these events. But it’s this close emotional proximity that makes the stories in The Missing Girl important, timely, and deserved of readers’ attention. Some parts may be difficult to read, but Doyle reminds us of the importance of listening to these stories—both hers and those echoing #MeToo around us.