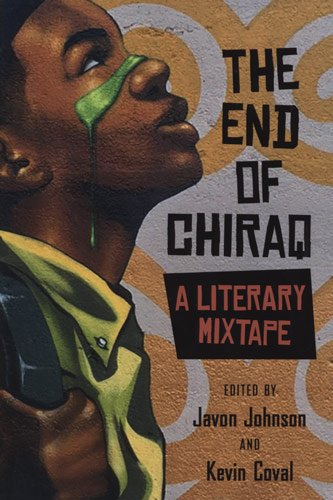

The End of Chiraq

Before reviewing The End of Chiraq: A Literary Mixtape, I feel obligated to mention the fact that I am from Chicago, specifically, the northwest side, where violence never really touched. Petty theft and the occasional flesh wound was about as “Chiraq” as Old Irving Park got. So, when people assume that all of Chicago is some Cormac McCarthy novel, they couldn’t be more wrong. This book is an attempt to prove that, and moreover, even where the unacceptable amount of death does occur, life is present too. The End of Chiraq is an anthology composed by the city’s youth, showcasing the beauty in the chaos, the “flower growing from the concrete” (Aneko Jackson, “Concrete Flowers”).

Before reviewing The End of Chiraq: A Literary Mixtape, I feel obligated to mention the fact that I am from Chicago, specifically, the northwest side, where violence never really touched. Petty theft and the occasional flesh wound was about as “Chiraq” as Old Irving Park got. So, when people assume that all of Chicago is some Cormac McCarthy novel, they couldn’t be more wrong. This book is an attempt to prove that, and moreover, even where the unacceptable amount of death does occur, life is present too. The End of Chiraq is an anthology composed by the city’s youth, showcasing the beauty in the chaos, the “flower growing from the concrete” (Aneko Jackson, “Concrete Flowers”).

The book was edited by two poets: Javon Johnson and Kevin Coval. Consequently, poetry seems to be the dominant medium throughout; however, essays and interviews are braided in, providing accessibility for right- and left-brainers alike. The book is divided into five sections, and it’s supposed to be digested in the same manner as a mixtape (“Make a ‘playlist’ of your favorite works, re-read them, repeatedly, run them back, share them” [Johnson and Coval, “Preface”].) I find this rather enjoyable, especially when questioning what exactly separates a poem from a song. What makes Pusha T so different from Elizabeth Bishop? Young Thug from William Carlos Williams? When you tear down these preconceived (and, honestly, outdated) notions of what it means to be “scholarly,” it isn’t difficult to see that any one of these unsung voices that use “ain’t” instead of “are not” may, indeed, be your next Whitman, Sappho, or Shakespeare.

The book touches on a multitude of subjects, including the Chicago Police Department, Spike Lee’s 2015 film Chiraq, and pretending to be a Chicagoan, all of which most contributors seem to despise. Some of my favorite pieces, however, are those that feel as if they almost don’t belong. For example, there’s a poem by Claire DeRosa titled “Daughter” in which the speaker discusses being Muslim in Chicago. There’s another, written by Demetrius Amparan, called “why do black boys smoke so much weed: For those who keep asking” that I’m particularly fond of.

At heart, The End of Chiraq revolves around the difficulties of growing up in Chicago’s underdeveloped neighborhoods. There’s a lot of talk of murder and gun violence and the media’s misrepresentation of the city. I find this puzzling. If we’re supposed to shed these stigmas, why continue to mention them, thus confirming what the news claims? The book contradicts itself in this manner, but neither Johnson nor Coval, nor any of the contributing authors are at fault. It’s just an annoying, lose-lose situation, in which we’re placed on the bookstore’s “African American” rack if we weep, and unpublished if we don’t.

Bothersome if we march, and stagnant otherwise. I understand that this “mixtape” is much more than publication, more than #BlackLivesMatter. It’s a peace-treaty with the general public, saying: “Here are the drugs and homicides, and all of the wonderful headlines that keep the Channel 9 news in business; we wrote about them so that you can get one last fix, and we, as a whole, can move forward.” Perhaps, that’s not what the authors are saying at all, but it could be advantageous if they were.

The last section of the book is titled “The Future of Chicago.” I was extremely excited to read this part, as I’m infatuated with all things relating to the future—although, if I had to choose, I’d rather spend my time pondering utopia instead of dystopia because it’s easy to imagine phones for hands, etc., but picturing the perfect world (for everyone) is no simple task. I was optimistic in thinking that The End of Chiraq would provide solutions to the problems that the city is facing, and I was a little disappointed when I got to the end of the book, and those solutions were missing. I am aware that one can’t go seeking answers, because “answers” don’t really exist, as one will believe whatever they want, but at least throw some out there.

“#BlackLivesMatter and . . . the Six Unconditionals: Excerpts from Taking Bullets” by Dr. Haki Madhubuti provides a few steps, such as: “Unconditional Love — for self, one’s family, one’s people, and all children.” How, though, is one supposed to accomplish this? I don’t know. Maybe my questions are equally as vague, some art-school workshop pseudo-help, but the only reason I ask them is because I, too, want to see Chicago blossom. I want to see unconditional love and the end of Chiraq. If you feel the same way, my one “answer” would be to read this book.