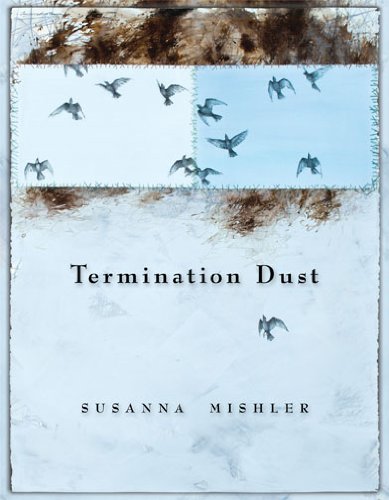

Termination Dust

Termination Dust is the fitting title of Susanna J. Mishler’s first collection of poems. As this Alaska-based poet describes in a poem, “termination dust” is the name locals use for the first snowfall in autumn: it names the meeting point between seasons, and suggests an essential ending and beginning. Moments of such meeting-grounds—between humans, between the human and the wild—are key elements throughout the wide-ranging poems of this striking collection.

Saying someone is a ‘nature writer’ can elicit interesting responses that seem to relate to how we’ve experienced the natural world. A poet acquaintance of mine once surprised me with a view that poems from a well-regarded ‘nature poet,’ full of observations of non-human lives, were too simple. Perhaps the lithe lines full of imagery and idea found in the opening poem “Afterlife: Ursus arctos” would confound anyone’s expectations of simplicity. Describing a brown bear’s bones, Mishler writes:

Her skull halves meet in a suture that flows

like a meandering river, and

she without her skin and you

without yours are red cousins.

How confidently these lines move from a beautiful simile in the first couplet to unpeeling the connection between the bear and the reader under the skin. Observations of animals or other natural phenomena often are threaded into parallel observations the narrator is making about human life. In “Caribou,” a fast-moving herd of caribou appears to the narrator like “a bead of liquid mercury flowing / down the alpine valley.” The speaker imagines a scenario where caribou rush past her and her companion, the shocking closeness of these other lives, and a breathless feeling of “possibility, / our surfaces wet and new.”

Lyrical imagery is one of the main forces driving these poems—appropriate to the speaker in “Knock on Wood”: “The pupil itself is a hole / hungry for small beauties.” Equally key is the tone of watchful curiosity in the narrative voice behind these poems with subject matter as varied as a small universe. There are multiple poems that question death or disappearance from the world of the living, five of these with the word ‘Afterlife’ in their titles; there are several poems, written in third-person, which examine specific moments in the life of a young boy named Silas; there is a poem titled “Tired, I Lie Down in the Parking Garage”; there are poems in which tightrope walkers, missionaries, or gynandromorph butterflies play a role. Throughout, there is a fluid sense of wonder at what life offers and where it leads the imagination.

One area of mystery is scale and our shifting awareness of it as we go about our lives. The narrator of “Window Seat” is in a plane flying over a mountain range that looks “like sand pinched into piles” and the snowy peaks like a “meringue” whipped with someone’s spoon. “I am drinking / coffee with cream over all this fragility, feeling like / this metal tube with seats is no place . . . ” And then, for many lines, the narrator’s worries ride front and center—worries about the plane’s bumpy flight and whether others are “still swallowing their stomachs” and how glaciers “will be smaller when I land than when I left.” A swirl of moment-to-moment anxieties while she is “30,000 feet above the one thing I inarguably / belong to” surrounds her. Yet the real strength of the poem is how it moves from capturing this vulnerable experience to a glimmer of something else:

. . . and sometimes I feel the edge of my awareness

like the edge of a dime, a tiny perimeter

glinting in the dirt. Something too small to see from a jet window,

not even as it’s landing, when match-sized trucks

slide under . . .

The wobbly-ness of the narrator’s own thoughts and the space they take up emotionally is balanced against an image that has both precision and a ghostly quality.

This invisible line between the precise beauty and strangeness of the world and how it jostles our many perceptions and memories is where Mishler’s poems dwell. There are parallel lives here, and, as the narrator of “Note to Self: Parallel Universes” notes, “Everything comes true and / we will never shake hands with most of it.” Yet, the imagery and imaginative narratives of Termination Dust bring the possibilities near.