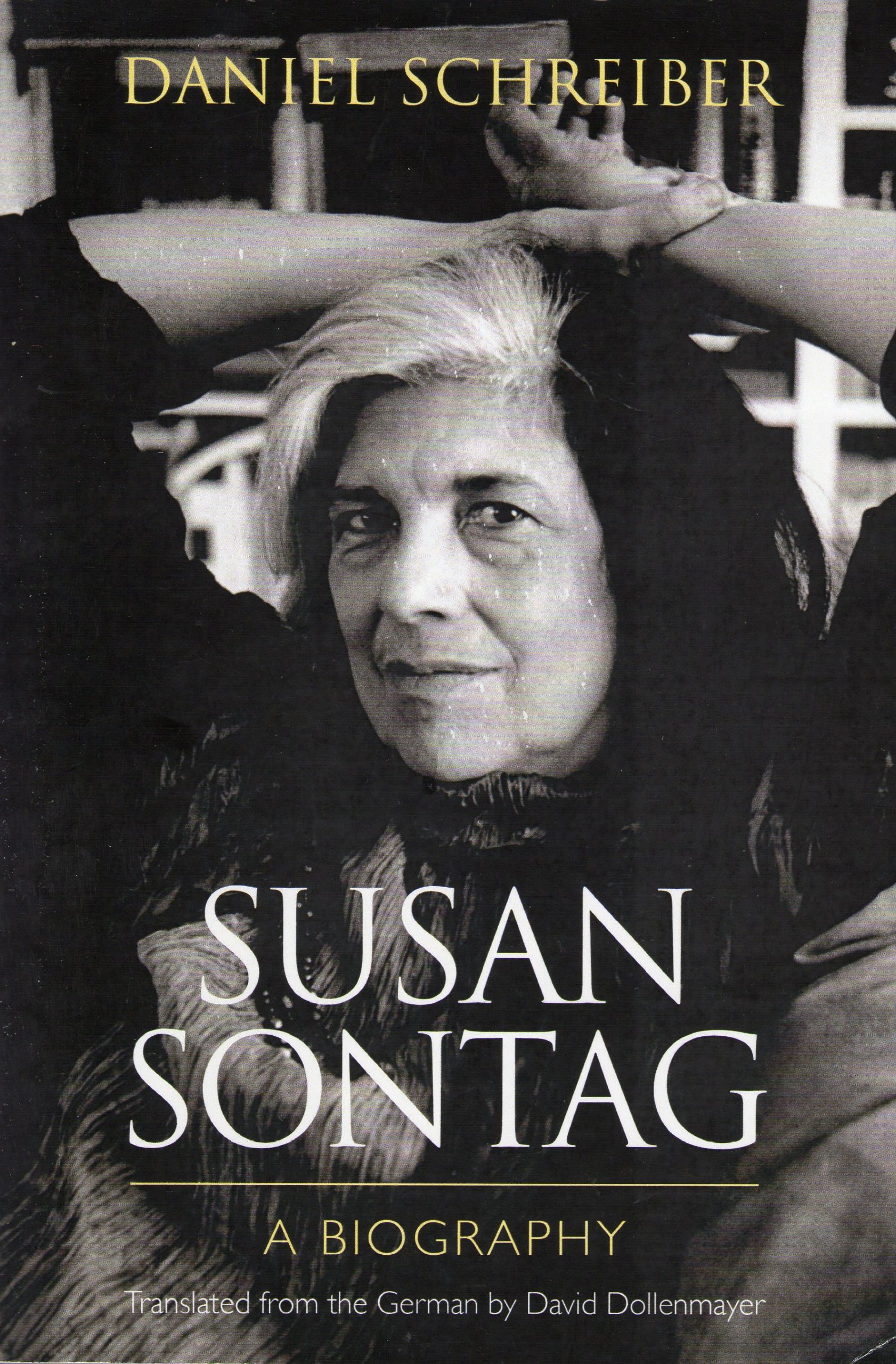

Susan Sontag

The first biography since her death in 2004, Susan Sontag: A Biography by Daniel Schreiber, gives a straightforward account of a very complex life. Sontag graduated high school at fifteen, married at seventeen, earned a BA from the University of Chicago at eighteen, had a son at nineteen, and was divorced at twenty-five. Sontag left the academic world, not completing a doctorate, as she explained, in order to explore the world intellectually on her own terms. She was a novelist, cultural critic, filmmaker, stage director, playwright, and political activist. She became an international pop icon and intellectual celebrity. She wrote about photography, illness, human rights, AIDS, media, minority rights, and liberal politics. When doctors told her twice she had cancers that were rarely survivable, she survived by her own efforts to find new treatments.

Schreiber organizes the material in comprehensible, short chapters on Sontag who lived several lives at once at the heart of the second half of the twentieth century uniquely on her own terms while engaging fully — and experimentally —with the era’s cultural changes. She defined and explored a “third aesthetic” she called “Camp,” an aesthetic “not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization.” She explored illness, challenging the view that a disease expresses one’s character which often leads to the attending association that one’s character causes the disease, e.g., cancer and AIDS. In Regarding the Pain of Others, she points out:

the viewing habits of a small, educated population living in the rich part of the world, where news has been converted into entertainment . . . suggests, perversely, unseriously, that there is no real suffering in the world . . . the dubious privilege of being spectators . . . of other people’s pain . . . consumers of news, who know nothing at first hand about war . . .

Her ideas challenged the status quo and defined the new processes in the changing culture.

There is a troubling underbelly to this biography. Schreiber presages the undertone he will take towards the accomplishments of Sontag at the end of the first chapter with, “. . . in her later interviews Sontag seems to have often fallen prey to the seductions of self-dramatization. . . ” and this kind of assessment is continued repetitively throughout the book. Schreiber’s attitude takes on “a questioning” of the motives and intentions of Sontag, usually by way of quoting others who claimed that Sontag went to the war zones of North Vietnam, Israel, Bosnia in order to gain media attention. He lets these stand without a counter balancing view. In the next to last chapter, Schreiber again lets a commentator, William Deresiewicz, give the negative interpretation of her intentions, “. . . While Where the Stress Falls won’t do much to enhance her stature as a thinker, never before has she made such large claims for her moral pre-eminence . . . she’s the first person in a long while to nominate herself so publicly for sainthood.” This analysis of Deresiewicz, the last words of the chapter, is left on its own as if it is an authoritatively correct take on this piece of Sontag’s writing, with the author standing in the shadows, letting negative insinuations stand unchallenged. Schreiber never questions these negative comments or what the motive was in writing such sarcastic commentary.

The other troubling aspect is the way Schreiber will interpretatively question Sontag’s choices. She did not choose to do the dissertation for the PhD from Harvard. She did want it, but chose to continue her own path. In her words about her decision, she said she had seen “academic life destroy the best writers of my generation.” Not letting Sontag speak for herself on this, Schreiber interprets, “It is not difficult to discern behind this remark a pose of wounded vanity.” This add-on seems unnecessary when we already witnessed the conflict in her own words. . . . Another example is when asked about her divorce, Sontag says in an interview that, “She had to decide ‘between the Life and the Project’—the Susan Sontag project.” “The Susan Sontag project” is another add-on. As a biographer, why step outside her words to put in such a free-standing authorial interpretation? What was “wrong” with her making the decision of how to live her own life. . . .

Schreiber’s biography does an adequate job listing the complex set of endeavors Sontag initiated and the many avenues that she followed responding to life, but he shows little regard to her accomplishments against the odds of an impoverished beginning. In the first chapter, “Memories of a So-Called Childhood (1933-1944),” Schreiber tells of the emotionally difficult first years she had with a mother who was a depressed alcoholic who left Sontag for months at a time, from the ages of one to five, with a nanny while she and Sontag’s father lived in China taking care of his fur business. Her father died of tuberculosis when she was five and the family went into social decline. Her mother took Sontag and her sister to Tucson, Arizona where they lived in a trailer on an unpaved road until Sontag was twelve. During these years, her escape was reading. Schreiber does understand that Sontag invented herself through literature and writing even as a child, and yet, throughout the book there is little understanding of how that was a motivating force for the rest of her life, to keep breaking free by invention. Despite her “reported” flaws—the sheer thrust of her life force and insight shines through, and does so inspiringly as a woman determining her own life at the level of a conversation with culture. The romantic view of the vocation of a writer that she formed in early adolescence, she parlayed by sheer verve to clarify the world until the end.