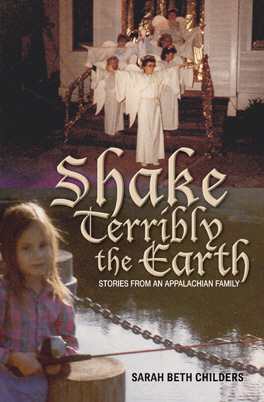

Shake Terribly the Earth

The word “Appalachia” can call to mind a host of stereotypes: poverty, fundamentalism, environmental exploitation, backwardness. Each word conjures up a vague image of a broad region that many have never visited. By contrast, specificity and personal experience come to the forefront in Sarah Beth Childers’s debut essay collection, Shake Terribly the Earth: Stories from an Appalachian Family. Here, in linked essays that consider family ties, faith, and history, Childers reveals her unique understanding of West Virginia as seen through her eyes and the eyes of her family. Through careful attention to the personal, these essays gently argue for the validity of each person’s understanding of their own world.

The word “Appalachia” can call to mind a host of stereotypes: poverty, fundamentalism, environmental exploitation, backwardness. Each word conjures up a vague image of a broad region that many have never visited. By contrast, specificity and personal experience come to the forefront in Sarah Beth Childers’s debut essay collection, Shake Terribly the Earth: Stories from an Appalachian Family. Here, in linked essays that consider family ties, faith, and history, Childers reveals her unique understanding of West Virginia as seen through her eyes and the eyes of her family. Through careful attention to the personal, these essays gently argue for the validity of each person’s understanding of their own world.

The fifteen essays included in Shake Terribly the Earth present vibrant images of Childers’s world: dignified Fundamentalist Baptists in suits singing four-part harmony, family reunions where relatives “[load] cobbler onto their dessert plates,” a former train-engineer grandfather who “glided over bumpy brick streets” in “a long white sedan” (“O Glorious Love,” “Through a Train Window”). In “November Leaves,” Childers writes, “My family communicates in stories,” and specific details keep her stories alive.

Although these stories sometimes come from distant generations, Childers most frequently returns to the more immediate stories of her parents and grandparents, choosing instances that reveal the ways family shapes us. She considers her mother’s insistence that her daughters have long hair because her own mother forced her to keep “a mass of short, tight curls” through childhood and an embarrassing attempt to become a cheerleader because of her mother’s own failed desire to do the same in her youth (“Scissors”). In Childers’s essays, the actions of past generations manifest themselves in thoughts and appearances, beliefs and desires.

Many of the most memorable scenes of Shake Terribly the Earth come in the essays focused on the author’s childhood in a Pentecostal church. Remarkably, Childers approaches her religious background with a candor that proves illuminating—she both expresses her doubts and affirms her continued faith. In “At His Feet as Dead,” Childers vividly describes her troubling failure with spiritual baptism at age ten:

Both Beryl and Ric began to pray in tongues, a rhythmic cacophony of syllables. They waited for me to hear the mighty rushing wind of Pentecost, for my face to bloom with cloven tongues like as of fire. The air grew dense. I felt my white hair ribbon slide down the back of my neck.

I began to cry. I felt overwhelmed by the significance of the moment and afraid everything had gone wrong. I knew unfamiliar words—grammatically accurate sentences from a foreign language—were supposed to rise from my spirit, glorifying and petitioning the Heavenly Father in ways beyond my mortal understanding. My job was to speak the words aloud. But I didn’t hear any words.

In this excerpt, Childers succeeds by providing the right mix of contextual information, internality, and memorable physical details. She continues to do this throughout the essay, melding the charismatic images of Pentecostal worship—swaying singers, shouting pastors, children crying out in tongues—with direct statements about both belief and doubt. “I was slain in the Spirit when I was thirteen years old, in an experience I believe was real,” she writes. But only a few pages later she parallels this with “I’ve prayed in tongues many times in my life, and I believe every word has been a fraud.” Childers’s honesty and keen eye for detail makes “At His Feet as Dead” the collection’s finest essay.

Although in many instances Childers proves her skill in mingling lively description and necessary explanation, several moments in Shake Terribly the Earth come out feeling flat because of heavy-handed statements. In “Through a Train Window,” an essay which juxtaposes Childers’s memories of childhood moments with her PaPa Ralph (the former train engineer) with her mother’s less-fond memories of him as a distant father, Childers writes: “I realize now that spending time with his grandchildren was important to PaPa, that he wanted to make amends for his workaholic past.” Throughout the essay, Ralph’s newfound understanding of the importance of time spent with family comes through clearly in memorable details such as clandestine trips with Childers to “McDonald’s, Jim’s Spaghetti House, and Captain D’s” after school, or savored details of The Lawrence Welk Show watched together. Childers knows how to bring memory alive, but in a few instances like this one, the essays might have benefited from a greater reliance on this strength.

Ultimately, however, Childers’s ability to select the right details and to weave together moments that throw one another into sharp relief make Shake Terribly the Earth a testimony to the importance of personal experience. She also advocates for gathering those moments and sharing them with others. “The Tricia Has Crashed,” the book’s second-to-last essay, does this clearly as it folds the grueling trial of driving her grandparents to Philadelphia to watch her uncle die from alcoholism-induced liver failure with cassette-tape voiceovers recorded by her father and uncles as teenage boys launching rockets in a field. In the car, as Childers’s grandparents worry about the last details heard from the doctor, Childers responds by “[rewinding] a few inches of tape and [pushing] play again. ‘Listen, Mark’s about to talk.’ Listen, I begged. Listen to your well and happy son. Out in a field in the morning with his brothers.” The stories told by her family, the moments recorded on tape or video, Childers’ own essays—each resurrect a crystallized moment of the past seen through each beholder’s individual eye. Shake Terribly the Earth presents these moments with noteworthy care and respect.