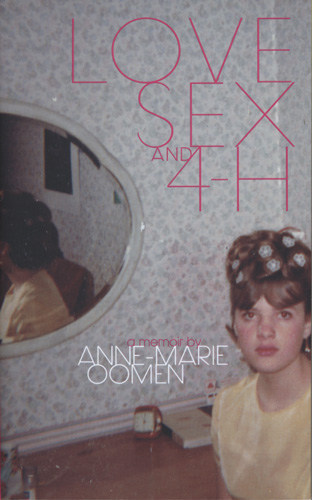

Love, Sex, and 4-H

I hate sewing. My mother loves it. To save money during my elementary and middle school years, I wore several of her handmade outfits enduring the shaming glances of classmates who, by the mid-80s, were sporting Guess jeans and Ralph Lauren t-shirts. Unlike Oomen’s adolescent experience, 4-H was less cool during mine, nevertheless, my mother enrolled me in a local club at age eleven so I could learn to make my own skirts and, to this day, I can sew a wicked tunnel stitch (though I seldom find good reason to exercise this skill). I hate sewing. My mother loves it. To save money during my elementary and middle school years, I wore several of her handmade outfits enduring the shaming glances of classmates who, by the mid-80s, were sporting Guess jeans and Ralph Lauren t-shirts. Unlike Oomen’s adolescent experience, 4-H was less cool during mine, nevertheless, my mother enrolled me in a local club at age eleven so I could learn to make my own skirts and, to this day, I can sew a wicked tunnel stitch (though I seldom find good reason to exercise this skill).

Anne-Marie Oomen, I acknowledge your genius, not only as a writer but also as a capable seamstress. I only made one skirt. Sewing machines revolt in my presence. I have a bit more success with a pen. But, after reading yet another of your literary works, I can only hope to someday be as phenomenal in my literary artistry as you.

Seriously, who could take the life of an average adolescent growing up in rural Michigan fraught with sewing projects, virginity, canning, and high school dances, and produce a memoir so intriguing that, despite my attempts to speed-read, slowed me into thoughtful contemplation and even brought me to a complete halt now and then as I marveled at these deeply connected sentiments? Oomen can. (Am I allowed to say this is the best memoir I’ve ever read?)

Shockingly, this memoir is about some of the most mundane, common, experiences of a young woman’s life. A skeletal synopsis would simply address the fact that Oomen grew up during the 60s, was Catholic, lived on a rural farm in Michigan, was poor, picked and canned garden grown food, joined 4-H, made her own clothes, had three boyfriends, and went to Grand Valley University after high school, the end.

But this is not a fair assessment of Oomen’s narration. She does more than tell her story . . .

She cuts deep into the fabric of adolescent existence and demonstrates why it is definitely drama, not mundane but months and years of tireless shifting, adjusting, aching, gaining, losing, running away and coming home again:

You are scared but not too scared, though you think about the Greens’ house, the small bedroom where you stay and wonder how you will get back there. But you are here now, on the road, with air whooshing through a side window, going faster. The radio is blaring hot town, summer in the city, and the other car falling behind. Why is that? But the kids from the Drift Inn laugh, and you are all thinking, We are doing it, riding around the roads, tooling around outside of Pentwater! You look at the dishwasher boy, younger than you, and think how sweet he is and wonder if he is too young to kiss. You can’t help it, but you don’t kiss him because you are startled by this thought that you could try to kiss someone, someone you don’t even know very well. You could do the kissing. What a badass idea. But it fits. Out there on the roads, it comes into your head, and you start to think about it. Could a girl really kiss a boy?”

She substantiates the notion that a single dress can completely alter a young woman’s history:

That night, I stood in front of her dresser mirror and scrutinized this image. The maroon fabric was understated but also . . . what was the word? Elegant? Was that possible? After all these years, had 4-H played a successful card? Beyond anything I had ever expected, the A-line slimmed in front and back, the zipper lay flat as a good field, and the skirt length skimmed just a quarter inch north of alarming. The lace caught the eye at each shoulder and fell to the wrist. That night, in front of the mirror, I felt like the outside me recognized some person on the inside who had stepped forward briefly into my mother’s chipped mirror, and that creature was pretty, and strangely refined. I knew she would disappear.

She confirms that, in youth and ignorance, lives are too easily conceived and too casually discarded:

Lydia stopped coming to lunch in the art room, looked pale in the mornings. She came to an away game with her boyfriend. To the next one, a home game, she came alone. She talked to me about it once, I think, but I had become like the person I once was hurt by, aloof to those unlike me. I had my club, my group, and even if that group had become diluted by absence, I had an identity that would carry me, for good or ill, through senior year. I think she told me the next part in early fall. “I’ll need to drop out soon.” She squared off her books, lining up the corners.

“Drop out?” My jaw dropped. Were we talking about her? She was pretty and smart. Why drop out?

“I’m starting to show. When I really show, then they want me to take classes at home.”

She confirms that a kiss is never just a kiss:

In a shadowy dark punctured only by headlights racing beyond the glass, he leaned down, and when his lips were a breath away from mine, I slapped his face so thoroughly that he touched his cheek, surprise in his eyes. Then a flicker, a tightening of the jaw. He pulled away, slipped his arm off of my shoulder. I felt it crumble, the entire ship that had set sail weeks before, made of tissue that could not hold. I grasped my own hand in my lap as if it would rise again and I would have to hold it down.

She presents argumentation that foreplay is sex (if we’re not being technical):

Somewhere in English class I had learned about metaphor. But it had been all linguistic, not physical metaphor. I was about to encounter the physicality of metaphor. Then good Father said, “The penetration of the tongue in the mouth is like the penetration in the act of sex.”

Light my fire, baby. We were getting specifics now.

“It’s like sex?” a shaky voice from the back asked for confirmation.

Father nodded. Dead silence.

Sigh. “Thus, it puts you in the way of mortal sin.”

By deduction, French kissing was not mortal sin but could put you in the near occasion of mortal sin, which was real sex in the flesh, which was mortal sin, unless you were married.

She proves that the extra-curricular activities and clubs we join in our youth unalterably shape us for the future:

I would always know how to make something from little to nothing, would always know how to look at a pattern, to take whole cloth and shape it into an actual thing to be worn with grace. The possibilities in the act of making would always excite me no matter how inadequate the materials. I would become a being who made things. As I turned the corner into the seventies, I would rely on that and the deep corollaries of what it meant to give my hands over to some work and to have my healthy ordinary life.

And she acknowledges the reality that growing up in the 60s was not a turbulent time for everyone, at least, not if you grew up in Hart, Michigan:

If we had listened, we would have heard not the dirty vibrations of oversized speakers but the underpinnings of the culture shaking loose. Outside of that gym, beyond the town and the lakes, civil rights workers demonstrated, a war escalated, and protesters marched against that war on both east and west coasts. But we were of the Midwest, or rather, not quite the Midwest but the Great Lakes, and not even the great cities of those Great Lakes but a small town set inland of those inland seas.

In that moment, what we heard was not the march of change but the beat of Aretha Franklin and Jimi Hendrix blaring out the open doors and those newly plowed fields. We would be blind for a long time. . . .

In truth, this was my mother’s era, the 60s with its race riots, assassinations, and musical mayhem. Growing up in Michigan herself, I am fairly certain that she was, like Oomen, preoccupied with boys, skirt lengths, and getting her hair to lay just right.

But Oomen’s memoir has something to share with everyone, not only her peers. Even as part of a generation removed from her experiences, I cannot gush enough about the sincerity and scope of this memoir. Again and again, she ripped my seams and turned the fabric of my being inside out. Oomen’s literary skills are fantastic, absorbing, transformational, psychedelic, and surprisingly such since they merely articulate the life of an overly-dramatic adolescent woman picking produce, sewing her own clothes, and learning to kiss during the 60s while nothing else much happened in her ultra-rural Michigan town.

Love, Sex and 4-H. C’mon reader, admit it, if nothing else you’re curious about this memoir simply because the title combines sex and 4-H. It’s like foreplay. What will you do next?