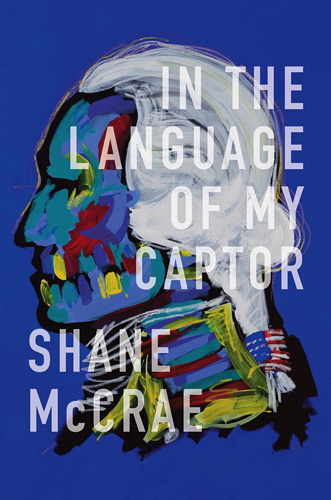

In the Language of My Captor

When I began reading Shane McCrae’s In the Language of my Captor, an 86-page book of poems and prose highlighting racial prejudice in both historical and present contexts, I was not the least familiar with the story of Jim Limber, an octoroon (1/8 African ancestry) orphan taken in by Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina, from 1864 to 1865. Growing up in the American north during the 80s and 90s, I learned Civil War history from a northern grade school perspective that celebrated the greatness of leaders like Abraham Lincoln, the importance of the Union, and that highlighted the incredible progresses made toward racial justice then and since. Limber was not part of that learned history.

When I began reading Shane McCrae’s In the Language of my Captor, an 86-page book of poems and prose highlighting racial prejudice in both historical and present contexts, I was not the least familiar with the story of Jim Limber, an octoroon (1/8 African ancestry) orphan taken in by Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina, from 1864 to 1865. Growing up in the American north during the 80s and 90s, I learned Civil War history from a northern grade school perspective that celebrated the greatness of leaders like Abraham Lincoln, the importance of the Union, and that highlighted the incredible progresses made toward racial justice then and since. Limber was not part of that learned history.

But I’m glad he is part of it now, thanks to McCrae. In fact, McCrae’s book could not be more historically timely. In the United States, for obvious reasons, we’re talking about race again, among a number of other things that fall into categories of social injustice, violence, white privilege, male privilege, and extensive politicizing. Problematically, when we start to volley terms and phrases about injustice, privilege, and violence, we risk getting caught in the back and forth motion of the verbal game, losing track of what words mean or, more importantly, what the experiences we are speaking of feel like. After all, politics is about people whether we remember this or not.

Poetry has always been political or socially concerned in some sense, often even subversive. But it does something of far more value, in my opinion, than simply stirring things up: it feels. It cuts to the heart of what it means to be human in situations where racial prejudice is evident, or privilege is enacted against the powerless, or violence is politicized to the point that victims become nothing more than headlines and news matter. In the Language of My Captor is a collection of poetry and prose that curates a human drama, giving voice to a victim’s strained existence—the tension between realizing outward oppression and limitations while also acknowledging one’s own disposition to enact violent and enslaving behaviors as well. This collection breathes, from rhetoric to rhythm, drawing upon a familiar dialogue between self-proclaimed saviors and those they have saved, between entrapment and animating a kill.

“Sometimes he says I’m lucky / to have been rescued from my gods” reads the first poem in the book. And with this poem “His God” I cringe mightily—this is poetry I understand too well; poetry I feel. While never having been impaled on the sharp tip of racial prejudice, I have been sliced to pieces by patriarchal values supposedly handed down by a Christian God, with reminders that this slicing is for my good, my benefit.

McCrae beats this oppressive rhetoric into the shape of poetry, poetry that stammers against itself in a way that reveals both internal and external fears and complexities. Notice the winding and broken streams of language in the collection’s third poem, “Privacy”:

If he would listen I would tell him

Privacy is impossible

If one’s community is

Not bound by loveInstead I tell him where I’m from we

Have no such concept

If he thinks I am / Too wise

he won’t speak honestlyAnd so I make an / Effort to make

my language fit his

Idea of what I am

I find with him and with his guestsBecause I’m on display in

A cage of monkeys

I / Must speak and act

carefully to maintain / His privacyand // If he would listen I would tell him

Where privacy

Must be defended

There is not privacy

Punctuation (slants placed like an afterthought and no other punctuation in the poem), forced variegated pauses, stanzas beginning mid-phrase and mid-stanza, and inconsistent use of masculine and feminine beginnings (upper- and lowercase letters used invariably to start a phrase) suggest rumination, trepidation, and shame. In fact, the poem on the following page is titled “What Do You Know About Shame.”

So what do you know? If nothing, McCrae will tell you that it means he cannot “talk about the place I came from” while simultaneously not wanting it to “exist / The way I knew it / In the language of my captor” (“In the Language”). He will tell you that it is about losing one’s memory of one’s own story after a stranger reframes it for you. I cannot argue with your point of view the poetry breathes back because I do not remember my identity. And yet, even in this poem, McCrae gifts his audience with the speaker’s identity:

Beyond the people / I knew

before and when I met new people

The first thing I assumed was

they were just like me

And then:

And so at first I thought the white men / Were ghosts

one spoke my language

And said that he had spoken to my father

I did not fear themI thought they had been

whitened by the sun / Like bones wandering

I thought I could / Help them

I thought they didn’tKnow they were dead

In a word: powerful.

And subversive—to say that the man who has come to save you is or was, from your perspective, whitewashed and dead. And how human to feel deeply that you can help this savior, bring him back to life.

Thus far, I have only considered the first third of McCrae’s book, but I hope that it is enough, that it has whetted your appetite. McCrae’s speaker changes personas throughout his work—though perhaps better to say that the speaker simply presents his humanity from a different angle; those angles being that of the caged animal to the voice of Jim Limber to the confessions of a Banjo, a “free” black man in the South post-slavery to the confused, angry, and even violent discoveries of a more modern marginalized youth. Limber’s poems are particularly stirring because we have so little real history about this young man. McCrae invents the boy’s psyche, reexamining the role of captivity in the life of an adopted colored boy that a white Confederate leader’s wife rescued from his violent mother.

Such a confusion of violence. Such a real expression of our human condition in a world of individuals both oppressing and oppressed.

It took me a long time to sit down and write this review because I wanted to do this book justice—but, believe me, it does this work on its own. Given our present cultural and political divides, you and I need this poetry. We need voices like McCrae’s to remind us that none of us are rightly positioned to be another’s savior. We are here to learn from one another. The way I, as an emerging poet, am learning so much right now in terms of content and craft from reading this book by McCrae. In close, before you reach for your phone to order this book, contemplate these final few lines from “Jim Limber the Adopted Mulatto Son of Jefferson Davis Visits His Adoptive Parents After the War”:

the man he said part of momma

Varina part of daddy Jeff alread-

y was burning in Hell I ought to join themHe said we might see good from seeing each other

Tortured we might finally see each other.