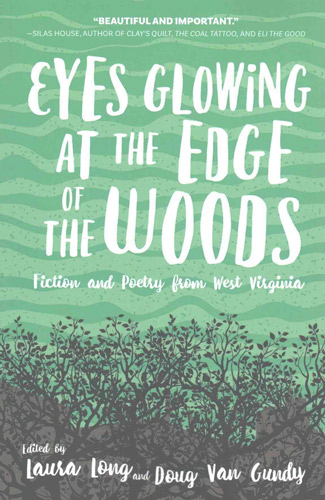

Eyes Glowing at the Edge of the Woods

One should think of reading Eyes Glowing at the Edge of the Woods as a welcome to West Virginia. Sixty-three West Virginians fill this anthology with vivid poetry and fiction that serve to characterize their “wild and wonderful” state.

One should think of reading Eyes Glowing at the Edge of the Woods as a welcome to West Virginia. Sixty-three West Virginians fill this anthology with vivid poetry and fiction that serve to characterize their “wild and wonderful” state.

Bears figure large in some of the most suspenseful pieces. Matthew Neill Null’s “Natural Resources” tells about a time when the bear population in West Virginia dropped to fewer than 500 and so were given sanctuary on public land. Cars and trucks lined up “at a distance you couldn’t call safe” to watch the bears feed from the county dump. Null vividly describes a chilling incident:

A woman drove there with her children. [ . . . ] She took the boy, smeared his hand in honey, and put him out there so sweetness could be licked from his fingers. Moans and nervous laughter from the cars. [ . . . ] Two bears came loping.”

But bears aren’t the only dangers our writers describe. Though coal mining is in decline, it’s still a powerful subject in the minds of many. Mesha Maren’s story is “Chokedamp,” the title of which refers to an accumulation of gases in poorly ventilated mines. A young man named Billy begins relating this story of how his father’s death affects the family with these dramatic words: “When the Frazier mine collapsed all the oxygen sucked out, left the shaft an unlivable lockbox of carbon dioxidized air.”

Sheryl Monks shows her expertise in writing on Appalachia, educating me with another mining term in “Robbing Pillars.” Two men are miles deep when “they have cut a strip in both directions, and soon they’ll be coming back through the middle, robbing pillars it’s called, the most danger any of them have been exposed to [ . . . ] Once they’ve humped out the vein they’re working on, the robbers will come behind and start pulling the pillars, the mountain collapsing at their heels.”

For a change of pace, I read about Cliff in “Through the Still Hours,” one of several stories about gay relationships. In Jonathan Corcoran’s tale, Cliff meets Gerry for the first time: “‘Are you a murderer?’ I say, only half-joking, when his skin touches mine.” At their four-year anniversary, Cliff thinks back: ‘“Imagine,”’ I said then, ‘a world [ . . . ] where two men could go walking down the street arm and arm and the neighbors would just smile and wave.”’ As the story progressed, Corcoran’s writing was so affecting that I truly felt afraid for Cliff.

Another attention-getter is Natalie Sypolt’s “Lettuce.” Jen’s husband Matt lost his “left arm in an IED explosion, can’t stomach the blood and flesh of meat anymore.” Understandably, he becomes vegetarian, but then as Jen grates carrots, a macabre scene: “my knuckles went down hard and fast across those sharp teeth. [ . . . ] when I looked down I saw that a few tiny drops of blood had dripped into the salad bowl.”

Moving on to poetry, I like the pastoral description Mark DeFoe weaves in “August, West Virginia.” He writes of “the sun a blood orange gong,” “sycamore leaves crinkling,” and “peppers like happy green grenades.” My favorite line is:

We sit on the porch, watching the rain clouds pile,

listening as the thunder talks itself intoa downpour

Not to be overlooked is John Hoppenthaler’s moving poem, “A Jar of Rain,” about a woman who travels 400 miles with a towel-wrapped jar of West Virginia rain.

[Her brother] allowed how he’d miss it—

yearning green mountains,

misty Ohio River,

& mostly the rain,[ . . . ] It was what she could

still do, the only thing more:

to wash what ashes

were left of his—gutter

to river to sea—

with West Virginia rainfall

dipped up from a drum

whose surface October had

started to freeze over.

More stylistically worded lines appear in Angela Shaw’s poem about a marriage, titled “Crepuscule”:

[ . . . ] Again a lackluster

husband doesn’t show. A little missuseases the burnt suffering of a cat-

fish supper, undresses, slowly lowers

into a lukewarm tub.[ . . . ] Now the house confesses,

discloses her like a rumor, vague and misquoted.

A small number of poems and stories in this book contain dialect. I realize dialects are typical in many regions of the country, and though they’re pleasant to listen to, I have no patience reading them. I skipped over those pieces.

Nevertheless, readers will find Eyes Glowing at the Edge of the Woods to be a many-faceted armchair guidebook to the people and places of West Virginia. The authors in this collection define the qualities of their state that make it the place they choose to call home.