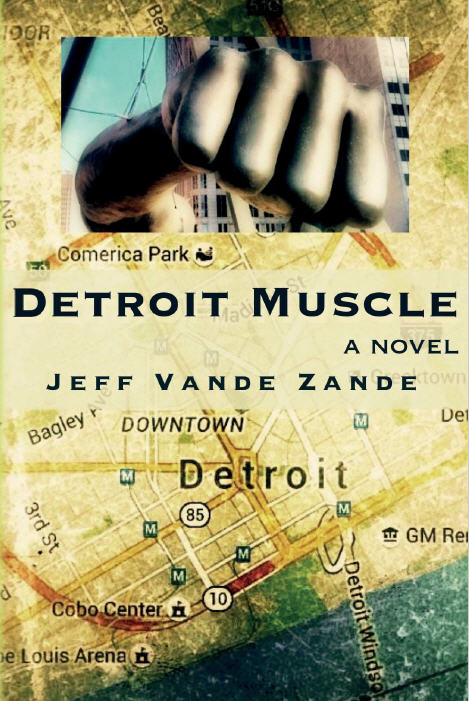

Detroit Muscle

Jeff Vande Zande burns the fat off our souls. At a recent poetry reading, the poet in residence, read a rather lofty ten lines about an experience in the California wilderness. Everyone stared ahead with reverence and when the poem finished, it was hard to tell if anyone noticed. He then told an anecdote about the origin of the poem. He used unpolished language and terse, powerful verbs, and, if I remember correctly, some foul language. Everyone laughed and looked around. I asked myself, “Why didn’t the guy write that as the poem?” Enter Vande Zande, who doesn’t settle for trying to sound like something. As a matter of fact, he almost eliminates pretense to a fault. He calls Detroit a “city of empty stories atop empty stories,” and in doing so strips the mystery from all of it while also alluding to that great hollow tale.

Jeff Vande Zande burns the fat off our souls. At a recent poetry reading, the poet in residence, read a rather lofty ten lines about an experience in the California wilderness. Everyone stared ahead with reverence and when the poem finished, it was hard to tell if anyone noticed. He then told an anecdote about the origin of the poem. He used unpolished language and terse, powerful verbs, and, if I remember correctly, some foul language. Everyone laughed and looked around. I asked myself, “Why didn’t the guy write that as the poem?” Enter Vande Zande, who doesn’t settle for trying to sound like something. As a matter of fact, he almost eliminates pretense to a fault. He calls Detroit a “city of empty stories atop empty stories,” and in doing so strips the mystery from all of it while also alluding to that great hollow tale.

Most of Vande Zande’s characters share desperation and despair. In a previous novel, Into the Desperate Country, the main character loses his family in a tragedy before the beginning of the story. Vande Zande’s latest, Detroit Muscle, begins self-inflicted pain. Robby, the main character is an addict, and an opiate addict at that. One of the most relentless drugs a person could face.

“Is this something you have to do for your program? Are you supposed to talk to people that you might have ” [ . . . ] “Because I’m not hurt or mad at you, not anymore. That night was a mistake, but it’s done. It’s happened.” Her hand goes to her belly and rubs gentle circles.

This sets the story up quite well. It becomes pretty clear that we’re dealing with the wreckage of the past from an addict of some sort. It all seems fairly standard and easy to digest. But this is just the mechanism at which Vande Zande uses to deliver his set of truths about the world. We watch as Robby begins to rebuild his life.

There is a great metaphor at work here. As the nation transforms from a production based economy to a service economy, cities like Detroit get a magnifying glass over them. Across the board, Detroit is known for its crime and squalor now, but only against the background of its once great machining industry. The entire country is losing its capital and production means. This has allowed Detroit to once again become the leader and innovator in how to rebuild. There is some evidence to show that it is doing so. The cheap land and easy acquisition has made it the goto for artists and creatives. Business has leapt through new endeavors there. Many other cities will get to mimic this before their city even hits the low that Detroit did. In Vande Zande’s novel, this social construct is acute.

We see in Robby, the formula for rebuilding and starting over. While many times, we don’t reach the desperation of a man returning from rehab, we all can use some of the can’t-quit spirit. But just the same, there is an almost pathetic nature that stays with Robby very deep in the book. He can’t shake his debt and seems to have no answers. His trip to Traverse City with Otto exemplifies what happens when people get a late start and doing the right thing:

“Good,” Otto says, “now push the tip of the leader back through that loop.”

His fingers follow Otto’s words.

“Okay, good. Now don’t pull it tight yet. Get some spit in your mouth first and suck on the loop.”

While this is far from a climactic scene, it is subtle enough to be embraced by the reader. He is learning to fish; the art of fly fishing at that. In the trajectory of the story, there are still so many relationships to be mended and battles to be won, but there is an ease that comes through here.

The same with Detroit. While we are definitely still waiting for opportunity to trickle down to all the people, including socioeconomic and racially diverse populations, watching the growth of the arts and the concentration of so much good has provided a sense of ease that not only Detroiters, but the whole nation can take a look at. While Vande Zande is a master of the man vs. self tale and the simplified and stripped down line, this book is new in its dealings with the greater social climate. We are all Robby, fighting to become what we were always intended to be.