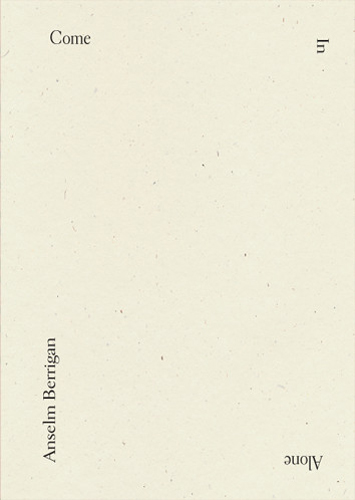

Come In Alone

I hate to focus so much on form, but in this review of Anselm Berrigan’s Come In Alone, form will take center stage. Or more accurately: form will frame the way we encounter Berrigan’s electric and vocally driven sensibilities. Because the very first thing you will notice when you open this book is the simple but profoundly innovative design, which runs all of the text as a border around an otherwise empty page. (You can look at sample pages here at the publisher’s website.)

I hate to focus so much on form, but in this review of Anselm Berrigan’s Come In Alone, form will take center stage. Or more accurately: form will frame the way we encounter Berrigan’s electric and vocally driven sensibilities. Because the very first thing you will notice when you open this book is the simple but profoundly innovative design, which runs all of the text as a border around an otherwise empty page. (You can look at sample pages here at the publisher’s website.)

This format might initially strike readers as gimmicky, but for as much as we talk about the space between the lines, about emptiness as a conditioning feature of poetics, I’m surprised I’ve never really encountered (even in the worlds of concrete or visual poetry) this simply conceived but radically reorienting layout, which does so much to give emptiness its primacy. Berrigan’s poems immediately force the reader to confront this emptiness as a powerful aesthetic force, and that alone is worth attention.

What the poems do after that, though, is even richer. When we first look at the page we don’t really get it, but then we catch the lines, literally in our peripheral vision, like little flashes of motion at the edges of our sight. This kind of flitting movement—compelled by the layout—commands Berrigan’s syntax as well, which pulses with vocal hisses and stutters across elisions, tmeses, abbreviations, slang, and other syllabic alterations. Here is an example (a note on citations: I will use arrows to indicate the margins on which the text is running):

[↑] sh sh sh sh sh [→] in the drone, the forensic archival feast, magnanimous hemorrhoid triumphal, overly, overly pre-[↓] sent, joy a mask, eco a mask, or or or or hepatitic imagination of used élan begets sentiment to be officious, a thing to be done [←] dinotopic. . . .

These lines are, no doubt, aurally driven, and “driven” is really an apt word—once you commit to the periphery and get comfortable there, you find yourself driving these poems, turning the book like a steering wheel in one continuous circle as you read along each margin. I highly suggest that you read this—as I did—in the most public and crowded places that you can; the profit in quizzical looks is quite satisfying.

But drive as you might, you never reach your destination: the poems never definitively end, instead cycling in perpetuity like a tape loop. You can stop reading whenever you want, but it never really feels like an end. Likewise, you never really begin these poems. You are compelled to start at the top left corner, but often that position is smack in the middle of a clause (though many of the poems do have a natural beginning there, often the clause starting just before, like a small grace note up the very top of the left margin. The effect is like winding back ever so slightly, then springing forward into the rotation of the poem):

[↑] so many [→] more people than today, there goes scale again, ape on fly in space, where here so little’s [↓] known, to a maybe’s delight, “my apple pie kicks ass,” wanting all gift-giving to come down on socks, plus giving up planning [←] to take over a world. . . .

Berrigan’s lines can be challengingly elliptical and his clauses densely packed, creating a difficulty that is exacerbated, no doubt, by the range of his ingredients, whether powerfully deep images, snippets of conversation or casual thoughts, memories, things overheard, and sometimes just fusillades of words and concepts (all irregularly punctuated, I might add). The effect can often be a delightful noise of too-many-channels-at-once, but it is also reminiscent of the wanderings of familiar New York poets like Frank O’Hara and James Schuyler. And fairly often a more present signal does worm through, Berrigan clinging onto a thought, either as an inexorable throughline that makes up an entire poem, or in something a little more rhythmic, like this anaphoric example:

[↑] & it’s more fun to be a shambles [→] of a person, with or without character, than it used to be, now it’s more fun to be Brigadoon [↓] than it used to be, & it’s more fun to forestall doom than it used to be, it’s more fun to care specifically than it used to [←] to be. . . .

We can see in this unevenness—in the combination of both the elliptically random and the tenaciously held—a conceptual tension between evanescence and sustain. Formally, these poems remind me of a piece by the artist Bruce Nauman, “Going Around the Corner Piece,” in which you walk around a giant cube wired with video cameras and monitors at every corner in such a way that every time you turn one of them, you see yourself from behind in the next monitor as you slip around the corner—i.e., you are always watching yourself slip out of view.

These poems work in the same way. This stream-of-conscious is constantly banking around right angles—thoughts are constantly slipping out of view (albeit they can slip anywhere in these poems)—and yet there is this cumulative looping effect, an infinite spinning (again, around an utterly blank page) as of a platter of data or the incantations of a religious text. Berrigan hints self-reflexively at this balance (“elimination” and “holding”) in the last poem, which functions as a kind of ars poetica:

[←] it did one thing for me: eliminate composition, arrangements, relationships [↑] time, all this silly talk about the line, voice and form because that was the thing I wanted to get hold of I put it in the center [→] of the space ghost. . .

This is a highly innovative collection that deeply understands the form it has chosen, and it is definitely worth your attention beyond mere curiosity.