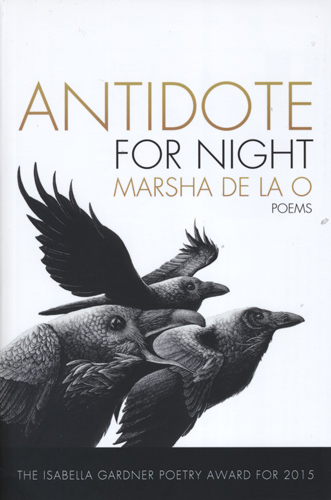

Antidote for Night

Marsha de la O situates her poem “Crossing Over” in time and space as follows:

This time of year, gold lingers

in thin autumn air

ether-light shining

crossing over [.]

Marsha de la O situates her poem “Crossing Over” in time and space as follows:

This time of year, gold lingers

in thin autumn air

ether-light shining

crossing over [.]

Evoking the Day of the Dead, when the veil between the living and the dead is especially thin, the poem nicely encapsulates the book’s mood. Antidote for Night is filled with omens, dreams competing with nightmares, and fears and questions of fate as much as it is a book about the family unit and hardship and joy and struggle.

The book is ostensibly set in modern day California, but aside from occasional place markers and setting details—orange groves and earthquakes both appear in the book—the poems tend to feel more unrooted and spectral than anything else. de la O may be a California poet by virtue of her location, but the terrain of her poems is far more spatially fluid than this categorization suggests. The poems are rooted in lived experience, but the perspective nonetheless feels otherworldly.

Antidote for Night is the winner of BOA Editions 2015 Isabella Gardner Award for Poetry, and it is a rich collection, with poems of varied forms but a consistent tone holding the book together. The diction is surprising and precise, as when de la O writes in “His Burning Cloud” that “A bee drills its zero / into wood, and oleanders,” the use of the word zero is immediately strange and spot on. Later in the same poem, the speaker’s mother urges her children to pray, “in a ropy / Voice to a full quiver of kids[.]”

de la O’s preoccupations are universal and haunting: she revisits childhood fears and her mother’s superstitions, and continues to be touched by them into adulthood. So, too, the speaker’s minor betrayal—with her siblings and father—when they go tubing against their mother’s wishes—seems almost to be paid for by the mother’s subsequent illness and death, later in the book, and in the speaker’s life. Guilt, worry, and the fear that what is precious will be stolen away function here as necessary counterweights to satisfaction and joy.

Are our lives fated? Or is what happens to us random? The question appears over and over again in different contexts, until finally, the speaker concludes, “it’s ravishing, that sense that fate is upon us.”