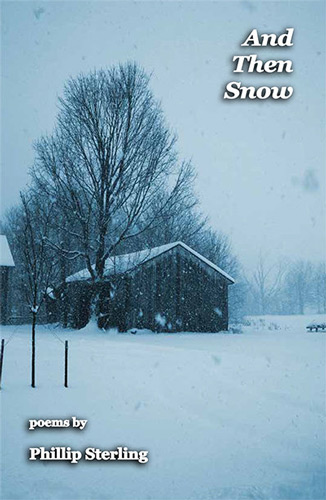

And Then Snow

By some stroke of luck, I had Philip Sterling’s new book with me as I laid in bed, sick from the change in altitude after arriving in Bogota, Colombia. As I choked down saltines and felt sorry for myself, these self-effacing, wise, and often revelatory poems delivered me from myself for a few hours. By some stroke of luck, I had Philip Sterling’s new book with me as I laid in bed, sick from the change in altitude after arriving in Bogota, Colombia. As I choked down saltines and felt sorry for myself, these self-effacing, wise, and often revelatory poems delivered me from myself for a few hours. Just as Sterling interprets snow in many unexpected ways, my pounding headache became interpreted as a joke, an inheritance, a gift.

The theme within And Then Snow that I found most appealing was a sort of gallows humor: in many poems, death flirts with our absurd human condition. “After Vallejo” repeats “I will die” as it documents a speaker’s mundane preferences—“I am better / in the morning”—and his preoccupations, such as his students,“that come and go, chatting of desire, / restless with desire.” In the end, only “some bright student” notices his death: “Look, he is no longer here!”

In other poems, the speaker alone parses out the impending reality of death. In “November 2,” the speaker shifts perspective beyond himself: “I will not ask / if the clothes I wear / are the clothes I will die in.” Instead, he is inspired by sailors sleeping in “net-knotted hammocks,”—“when they died / (shrouded by their handiwork) / were recast to the sea.”

A surreal quality at play within some poems implies the spectral quality of our existence and delivers both a sense of levity and forboding. “Every Next Train” begins with a speaker taking up space in what seems an uncanny dream: “standing / as if on the platform of the train station / in Louvain, inappropriately dressed.” Next, together with children along the tracks, the speaker is plaintively reminded: “Every next train is ours.” Snow, within a stunning conclusion, is the lift that transports: “we / will rise—as winter constellations—and / take the places reserved in our names.”

Other poems sink into a stronger sense of realism, such as in “Cards and Well Wishes Should Be Directed to the ICU,” where a speaker grapples with resentments as he drives to visit a dying boss. In this case, snow begins banal, “making travel difficult,” yet shifts to transform trivial rancor:

[ . . . ] settling

its winding sheet, as if—indeed!—a shroud,

upon all that once looked barren and scraggled, all

garden rot and windfall, all the wrangled, second-

hand bicycles of summer’s immeasurable light

I will save the final two lines for your own reading, but this poetry labors to receive even the most frigid grace, juxtaposing the violence of nature with our deep need to escape our small selves.

Other poems exude what could be construed as a somewhat untouchable paternal wisdom; Sterling quotes Wallace Stevens’s “A Quiet Normal Life” at the start of the second part of the book, after all. Yet I found that erudition was tempered regularly with humility, tenderness and humor. Quite a few poems contained a speaker bowled over with the joy and passion, so along with the curmudgeonly speaker presumably cynical with “the politics of crows,” in “Grace,” we are invited to bow with the refrain “I am grateful” as he expresses gratitude, “For both the rain and the absence of rain” and repent as he repents, “Shame on my sadness! Shame on my loss!”

In “Lapse,” it is a dog who reveals the speaker’s regret for not fully appreciating the “subtle woofs” or the full spectrum of life’s moments, even those burdened with grief:

my father and the way I’d

stood beside his wheelchair the months before

he died, sampling the thin gravy

of a residence I’d made arrangements for

And is usually the case, the dog is ultimately our distinguished teacher:

releasing at long last a sigh . . . not so much

of weariness, but of something more

than a man of a mere sixty years might know:a sigh, I’d like to think, of snow.