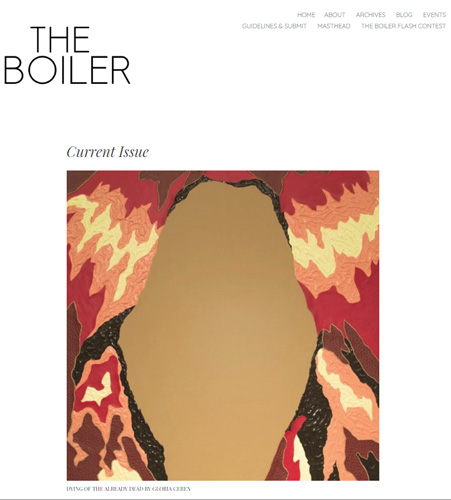

The art in the latest issue of The Boiler features paintings by Gloria Ceren and photography by Klara Feenstra. Ceren’s work evokes feelings of chaos and smoldering heat with warm colors and layered textures. Feenstra’s photography gives the sense of looking in from the outside, the overlaid image appearing like a reflection on glass as if the photographer took photos from the other side of a window. The writing in this issue of The Boiler echoes this: although we’re taking in the poetry and prose in this issue from the outside, the colors and chaos draw us in to examine it closer.

The art in the latest issue of The Boiler features paintings by Gloria Ceren and photography by Klara Feenstra. Ceren’s work evokes feelings of chaos and smoldering heat with warm colors and layered textures. Feenstra’s photography gives the sense of looking in from the outside, the overlaid image appearing like a reflection on glass as if the photographer took photos from the other side of a window. The writing in this issue of The Boiler echoes this: although we’re taking in the poetry and prose in this issue from the outside, the colors and chaos draw us in to examine it closer.

In nonfiction, Naomi Washer invites us into “Tension and Release: Diffusing Pressure Points in the Abnormal Adolescent.” Washer states up front: “My spine did not cause me pain. My body never felt wrong until they said it was.” And so begins treatment for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. It’s with this diagnosis and treatment that Washer feels different, feels like she’s living within an object to be “fixed,” as opposed to inhabiting a complex human body, each one different from the next. Washer explores the ways in which we—as adolescents and then beyond—are made to feel our bodies are wrong as they are. She drives this point home by speaking of treatment from a chiropractor: “the patient may feel as if the doctor is doing their best to rid the body of an evil spirit,” another set of “treatment” one can argue isn’t necessary. She carries this imagery throughout the piece, ending:

The chiropractor always asked me to hold my breath when he took the x-ray. I never knew if this was a necessary part of the procedure or not. I would take off my necklace, belt, and any other metal on my body. I would press my back against the x-ray wall as he stepped into the next room to flip the switch.

Hold your breath, he’d say. Then we’d wait.

Sometimes, I didn’t hold my breath. I let the spine escape through my mouth.

This is a beautiful image to end the piece on, showing both the ways in which Washer rebels against the system in this small, private act, while also underlining the importance of letting go of what is trapped inside us.

Tami Anderson’s “You Will Remember This” begins and ends with a tampon, a story that comes full circle. While a fiction piece, the mother/daughter relationship portrayed reads realistically. The first sentence grabs hold of attention: “The first time you hear the word ‘tampon,’ you will be just barely six years old.” It’s her mother’s tampon, her mother sitting “like she is sitting at a table in a four star restaurant instead of on a toilet seat. Your mother does not believe in closed doors.” Doors show up repeatedly throughout the piece as Anderson explores the idea of privacy and closeness in an oftentimes conflicted, mother/daughter relationship. The door is locked, lock checked “on the bathroom door no less than five times” before the narrator uses a tampon herself for the first time; there are closed doors when her mother was married to her stepfather and doors open again once they’re divorced; and there is a door at the end of a gynecologist’s hallway. Doors and tampons are an interesting choice for repeating themes, but it’s enjoyable seeing Anderson make them work. When we end on another tampon, the narrator no longer needs them, now postmenopausal as she uncovers it from under the bathroom sink. It is this discovery that sets off this exploration of family and self, a neat plot device to watch unfold.

While there are four other pieces of fiction to explore (by Jeff Ewing, Wynne Hungerford, Kate Millar, and Jennifer Popa), the poetry section has a lot to offer readers. Among my favorites were poems exploring aspects of womanhood and race.

Dorothy Chan’s speaker in “Ode to Nurses, Love Hotels, and Marilyns on the Covers of Playboy” sees two women dressed as nurses kissing in a gay club and it is:

straight out of my childhood

dreams of being like Hello Nurse

from Animaniacs, that blonde bombshell

sex goddess cartoon with cleavage stacked

like bookshelves and red lips even tastier

than the pizza she nibbled on in that scene

when Yakko and Wakko sing about her 160+ IQ

and multiple PhDs, but you know what

they were really drooling over,

leaving seven-year-old me to wonder

what place a little Asian girl has in this world

of ’90s Marilyn Monroes running in slo-mo

She goes on to question gender roles (“every time I’m attracted to a guy, / I think about what he’ll look like in a dress”) and what’s expected out of someone that looks like her. Chan questions: “what if I’d rather play doctor than / nurse, or teacher than schoolgirl, / or fly you rather than ride you?” What happens when we want to break outside the molds society has built for us? Chan is unafraid of questioning these molds, writing with wit and candor that she carries through to her other two poems in this issue: “Ode To Sexpots And My Mother’s Red Stockings” and “Ode To Sushi, Sashimi, And The Eels In The Tank,” which speak of family members with just as much honesty and ease.

Fatima-Ayan Malika Hirsi also speaks on being a woman in “Discussion on Drought,” and race in “(A Few) Reasons Why I Might Be Stressful to Work With.” In the first, the speaker questions her breasts, wondering if being a woman is reason enough for them to feel heavy and full or if there should be more meaning to it or life sustained by it: “doesn’t soil want nothing more / than to mother / seeds?” While not a viewpoint I share, I was still able to appreciate the imagery Hirsi chooses to convey her message. In the second poem, Hirsi places us in her rage, “a place / they say we have no right to visit.” She stacks up what everyone demands or expects against how she wants to be and act and react as a woman of color in the workforce. Now is the perfect time to read this poem and reflect on what we ask or expect of those around us.

For writing that smolders with heat and bubbles over with honesty and creativity, pull up a seat to The Boiler’s Fall 2017 issue and warm yourself.

[www.theboilerjournal.com]