“The body of a child is a playground” -from “Red Rover”

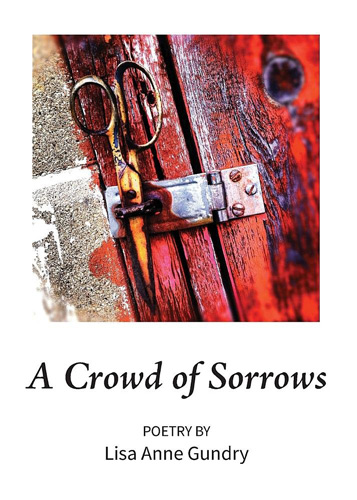

Lisa Anne Gundry’s often sparse lines of poetry about childhood sexual abuse and its lingering effects is haunting. While some of her poems reflect a juvenile attention to the art, Gundry’s grasp of the subject matter is spot on—partly because she lived it and partly because she has clearly carefully researched each phase of her own pain and healing and just as carefully referenced these phases in her work. At 116 pages, A Crowd of Sorrows addresses neither too little or too much, spanning accounts of the abuse, counseling, trauma, and the reactions of family members to her confession that her grandfather was a pedophile who had violated both she and her sister in cars and on couches, during the day and at night.

“The body of a child is a playground” -from “Red Rover”

Lisa Anne Gundry’s often sparse lines of poetry about childhood sexual abuse and its lingering effects is haunting. While some of her poems reflect a juvenile attention to the art, Gundry’s grasp of the subject matter is spot on—partly because she lived it and partly because she has clearly carefully researched each phase of her own pain and healing and just as carefully referenced these phases in her work. At 116 pages, A Crowd of Sorrows addresses neither too little or too much, spanning accounts of the abuse, counseling, trauma, and the reactions of family members to her confession that her grandfather was a pedophile who had violated both she and her sister in cars and on couches, during the day and at night.

“Once his fingers left my underwear / there was a tug and a metallic ziiiiip / before his hand sought mine / under the blanket,” says the child in “Safety Blanket.” Gundry masters a child’s voice in her poems with simple lines that say barely enough and evoke the innocence. While reading “Safety Blanket,” I can easily imagine the wide faraway gaze of the child who does not “say a word” while clutching “a pillow: / a Christmas gift from / [her] 4th grade teacher.” The same child who is encouraged to “look at that there on TV” as a blanket is pulled over she and her grandfather so they can “get snuggled in” and “just rock a little bit” in the persona poem “Over the River and Through the Woods.” The interaction between grandfather and granddaughter is implied almost entirely through the grandfather’s agency and movement, thereby suggesting the terrified compliance of the child seemingly beginning at age seven and continuing several years.

In fact, Gundry’s abuse survivor does not demonstrate real agency until after her grandfather dies, an event expressed in the poem “Judgment Day” when the two sisters visit his hospital bedside as he fades, “sure to stay just out of reach.” His death and the funeral poem are followed by Part III of Gundry’s book which begins with the survivor’s desire to finally speak about the molestation to a mother she knows is “the kind of mom I can tell anything.” But when she finally does speak up and tells her mother, her “Mom’s mouth is trapped in silent horror” (“Revelations”) and later, in the persona poem “Once Upon a Time,” it is clear that her mother cannot handle the truth about her father. “He was a good dad to me Lisa. He loved me,” she repeats twice while recounting the one time he had molested her as a child with “when he was drunk” added as a viable excuse for the event. “I didn’t know he would do that to you” she laments.

And while these accounts are harrowing enough, so are the poems about how childhood sexual trauma discolors all of the survivor’s future experiences and how they will react to anything that reminds them of the traumatic event. Gundry’s poems address these effects directly: “Most people who are abusers / were abused themselves” says the girl in “In His Image,” “I have to be careful / when I babysit for Billy.” As much as this fear might seem unrealistic, I know from personal experience that it is quite alive in the mind of the abuse victim who fears becoming anything like his/her abuser. And in “A Certain Kind of Man,” she expresses her constant fear around men:

It’s hard to tell him apart

from the others,

from the good ones.It just takes a few seconds to scan

a room when I enter

to check for anyone suspicious.I choose a table against

the wall

with a view of the door.

And the poetry becomes even more discomforting as the speaker carries her trauma into her adult life of overeating in “Camouflage (What Prey Does),” a relationship with an unsafe lover made more unsafe by the victim’s compliance in “Unarmed,” and the careless dismissal of her pain by a husband and a counselor in the poems “As Above So Below” and “Marriage Counseling.”

The final section of poems is my favorite because its poetry reaches deeper into what it feels like to be a survivor of childhood abuse with poems like “Dream Demons” and “Solace,” but you’ll have to read this manuscript and explore this territory yourself to see what I mean. And Gundry makes room for such exploration in her book by leaving each poem’s facing page blank to allow the reader space to “record (their) own reflections about, and reactions to, the poems . . . ” This is further proof that she considers her work more than artistic expression as it also serves as hallow ground to honor survivors and acknowledge their lifelong struggles and healing. I think she does this well. As a survivor myself, I found the work personally satisfying because it is always good to know that one’s own pain and process is shared by others—and now shared by every reader who will give it some space in his or her own life, consider its weight, and enlarge their empathy.

Given the stories of sexual assault that have recently swept our news circuits, such as the extremely light sentencing of Brock Turner, a convicted rapist over-valued for his athleticism, and the Baylor University sex scandal in which several young women were silenced to the “greater gods” of college football, I believe that audiences need to feel this weight—its extreme heaviness and long-term damage. Despite what our overly-sexed, athlete-worshipping culture would have us believe, victims are people too.

In A Crowd of Sorrows, Gundry brings her readers close to the survivor and demands that we intimately consider her life-long struggle to feel safe, enjoy relationships, value herself, and realize her dreams after experiencing childhood sexual assault. The consequences of sexually assaulting someone—the prison time, social alienation, and vocational losses—are not nearly as deeply felt or severe as the consequences a survivor will face for doing nothing other than being momentarily vulnerable to a predator.

Advocate for the survivors. Read A Crowd of Sorrows.