The Arkansas Review – August 2014

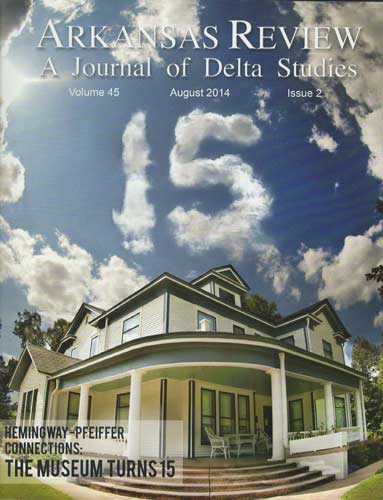

Ordinarily, this interdisciplinary journal (formerly the Kansas Quarterly), focuses on the seven states of the Mississippi Delta. This special issue of Arkansas Review grew out of the 100th year anniversary of the arrival of the Pfeiffer family in Piggott, Arkansas, as celebrated by the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center there. Its director, Adam Long, guests edits this exploration of the Hemingway-Pfeiffer connection. Ordinarily, this interdisciplinary journal (formerly the Kansas Quarterly), focuses on the seven states of the Mississippi Delta. This special issue of Arkansas Review grew out of the 100th year anniversary of the arrival of the Pfeiffer family in Piggott, Arkansas, as celebrated by the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center there. Its director, Adam Long, guests edits this exploration of the Hemingway-Pfeiffer connection.

Of Ernest Hemingway’s four wives, Hadley, the first, is often seen as the “best” one; Martha Gellhorn, the third, as the pretty one; and Mary Welsh, the fourth, as the one who was there at the end. Pauline Pfeiffer, the second, is frequently viewed as merely the one who took Ernest away from Hadley. But in his “Introduction: View from the Hill,” Long reminds us that not only was the thirteen-year marriage to Pauline one of Hemingway’s most productive periods, but she was also his best editor, the mother of two of his three children, and a substantial person in her own right from a substantial family. Pauline’s paternal grandparents emigrated from Bavaria in the 1850s. To name but a few accomplishments, the family founded what would become an international pharmaceutical company, funded Pfeiffer University in North Carolina, and produced a Harvard-trained New Testament scholar. Moreover, they supported Hemingway and Pauline financially and materially (giving them a place to live in Piggott, for example) for years and thus had an impact on American literature. The European branch counted among its numbers a German consul general to northern Italy.

Two articles take advantage of new correspondence recently acquired by the Museum: family letters owned by an aunt of Pauline’s and the private letters of Clara Dunn Zeleny, a friend of Pauline and her sister Virginia. Catherine Calloway speculates that Hemingway’s short story, “The Sea Change,” owes much to his interest in the lesbian relationship of Clara and Virginia. Calloway grounds her thesis in a survey of Hemingway’s other treatments of homosexuality and in a brief consideration of his friendships with such people as Gertrude Stein and the Pfeiffer sisters, who were said to be androgynous. Amy Schmidt’s “Forty Plus Coats of Paint: Pauline Pfeiffer-Hemingway as an (Almost) Delta Debutante,” suffers somewhat from a lack of editing and the use of such imprecise terms as “debutante,” “good breeding” and “elite” as sociological categories. As a result, what others may see as common female behavior of the time is cast as exclusively a southern phenomenon.

In “Medicine and Medicines in Hemingway’s Arkansas,” Alex A. Cardoni analyzes the medical content in the fiction Hemingway produced in Arkansas, tying it both to knowledge he would have picked up from his doctor father and to the Pfeiffer pharmaceutical business. Danell Ragsdell-Hetrick examines the death of Catherine Barkley in “A Farewell to Arms” and persuasively identifies the cause as a Twilight Sleep regime of drugs popular in that day, which for Hemingway would carry the Modernist message that unregulated progress is dangerous.

Teachers and students from the writers’ retreats at the Museum provide stories and poems, such as Pat Carr’s story, “The Milano Clock”; Roland Mann’s story, “The Broken Down Truck”; three Arkansas poems by Jo McDougall and more. Eric Laursen contributes a fascinating article, “Grounded in Reality: How Piggott, Arkansas Helped Create A Face in the Crowd.” This is local history at its best, for it links Piggott with national issues such as “the fear of the American mass” and the power of anti-intellectualism in the U.S.

The substantial book review section returns to the broader regional mission of the journal. Daughter of the White River by Denise White Parkinson, treats the case of an Arkansas woman at he center of a lurid web of murders in the 1930s. Three reviews concern the Civil War: The Little Rock Arsenal Crisis: On the Precipice of the American Civil War by David Sesser, American Civil War Guerrillas: Changing the Rules of Warfare by Daniel E. Sutherland (reviewed by David Sesser), and Civil War Journalism by Ford Risley. Parker Homestead: A History and Guide by Mary Ann Parker tells of an Arkansas landmark; and Visible Man: The Life of Henry Dumas by Jeffrey B. Leak chronicles the short, tortured life of an Arkansas writer who, had he not been shot by a New York transit policeman, would have contributed much more to African-American writing. Well-chosen photographs enhance the Hemingway-related material throughout.

The Arkansas Review, published at Arkansas State, is a must-read for people in the Delta. For everyone else, the variety of its content, even in a special issue, illuminates corners of culture you probably wouldn’t find on your own. A great read.

[www.altweb.astate.edu/arkreview]