Bellevue Literary Review – Fall 2015

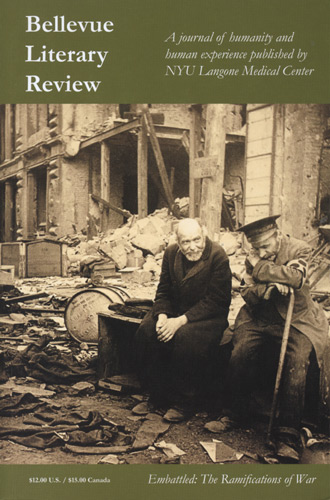

The Fall 2015 Bellevue Literary Review from NYU’s Langone Medical Center operates under the subtitle “Embattled: Ramifications of War.” Self-described as a “journal of humanity and human experience” this issue focuses specifically on narratives surrounding not only war, but war’s varying and often heartbreaking effects on the human experience. The short fiction, poetry, and nonfiction explore delicate topics such as PTSD, death on the frontlines, and post-deployment readjustments with an unflinching matter-of-factness paired with beautiful language. The Fall 2015 Bellevue Literary Review from NYU’s Langone Medical Center operates under the subtitle “Embattled: Ramifications of War.” Self-described as a “journal of humanity and human experience” this issue focuses specifically on narratives surrounding not only war, but war’s varying and often heartbreaking effects on the human experience. The short fiction, poetry, and nonfiction explore delicate topics such as PTSD, death on the frontlines, and post-deployment readjustments with an unflinching matter-of-factness paired with beautiful language.

The journal’s opening prose piece “Flat Mommy” by Shawne Steiger stands out as a story about an American soldier, or more precisely, an American soldier’s family, left to pick up the pieces after she dies during deployment in Iraq. Told from the perspective of an 11-year-old boy, the narrative depicts the family creating a cardboard cut-out of the mom to comfort them while she’s away, and ultimately growing unbearably attached to it after her death. It is full of poignant and heart wrenching moments such as the narrator trying to comfort the cardboard cutout after learning of his real mother’s death:

I propped Flat Mommy on the couch and sat next to her. I held her hand [ . . . ] I patted her arm, like I was the grownup and she was the little kid. “It’ll be okay,” I told her. “We’ll take good care of you. Maybe we can find a different picture. Maybe one with a nice dress or something.”

The piece concludes with the narrator’s surrender to the permanence of loss.

R.T. Jamison’s “Trees and Other Things We Might See from the Parade Grounds” comments on the various ways that veterans deal with the trauma experienced at war, and how they often fail in their attempts to cope. The piece features an elderly neighbor who has turned to alcoholism to numb the pain of his experience, an is interspersed with memories and explanations of his good friend James Wasson’s suicide following their deployment. The narrative voice is terse and sometimes downright harsh, betraying a kind of pain and hopelessness that the narrator is clearly trying to bury:

Talking makes it all better, they say. Talk therapy. Talk it through. Well, how many ways can I say that I don’t want to talk about it? To din on about the nightmares, the black and blue memories. About the shit I’ve seen. The shit we’ve done. The shit. The fucking shit. Fuck you and your fucking therapy.

The edition’s poetry features many poems in a variety of forms. All create impactful images, depicting a range of feelings and scenarios including soldiers on the front lines, families coping with military deaths, dodging the draft and much more. Standout pieces include “War Stories” by Pamela Hart and Seema Reza’s “Quartering.” Each employs a different form but also includes haunting language that leads to truly impactful writing. “War Stories” forgoes stanzas for a single block of text, beginning with the powerful first line: “Stories of War begin mid-sentence is one way to start.” It goes on to explore the mother’s role and personal concerns in sending her son into the military and off to war, leaving the reader feeling just as conflicted as the mother in the poem.

“Quartering” employs stanzas, line breaks, italicizing, dashes etc. to visually represent a woman’s anxieties concerning her decision to house a veteran (and stranger) in her home for the tax break. The poetry almost reads as a form of prose, telling of the woman forming a semi-relationship with the man, trying to accommodate him for what he’s been through, resulting in the powerful final stanza in which she realizes: “Every act of kindness has been an act of war.”

The journal features three pieces of nonfiction against the thirteen prose pieces and twenty-one poems, but the nonfiction does not take a backseat in the journal. It presents a variety of perspectives across the world and world’s timeline of war, beginning as early as WWII and ending as recently as the brink of the Iran-Iraq war. Each offers a first-person account of a life only imagined and recorded in textbooks, personified by concrete details that can only be captured by personal experience, all with powerful endings. For example, Leopold Szor concludes recounting his WWII internment camp experiences in “Obligation” with the assertion that “Survival confers no automatic nobility. It bestows only an obligation to speak out.”

I find it safe to say that Bellevue Literary Review achieves its goal of capturing “humanity and human experience” with its “Ramifications of War” issue. Each piece, regardless of genre, employs a unique concept and perspective, but overall their agreement is the same: war’s effect is intense and enduring, and will not stop being present in the human experience anytime soon.

[blr.med.nyu.edu]