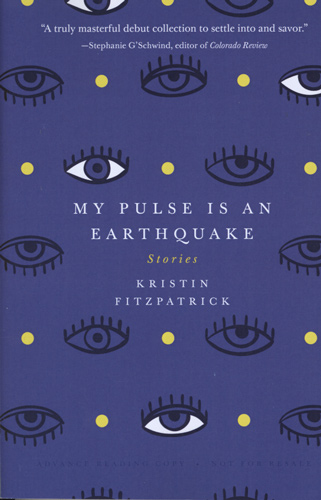

FitzPatrick’s debut collection, published by the Vandalia Press imprint of West Virginia University Press, consists of nine powerful stories about the fragility of hope, the devastation of grief, and the precarious balance of family harmony that lies between the two. Four of the nine stories feature the same characters, allowing us to see growth, and sometimes the lack thereof, in the lives of these individuals. FitzPatrick’s debut collection, published by the Vandalia Press imprint of West Virginia University Press, consists of nine powerful stories about the fragility of hope, the devastation of grief, and the precarious balance of family harmony that lies between the two. Four of the nine stories feature the same characters, allowing us to see growth, and sometimes the lack thereof, in the lives of these individuals.

In “Queen City Playhouse,” teenage Tess is a Catholic-school dropout who works as a scenery stagehand at the local theater, while caring for the theater’s terminally ill owner, Mr. Deusler. When most of the cast comes down with a vicious stomach flu the night before the first show, Tess is called upon to act in the lead female role, opposite Joe, her bad-boy crush, who may not be as kindhearted as she’d once believed. As Tess hovers over Mr. Deusler night after night, she thinks of her own broken family, and of the brokenness of the Deusler family, none of whom sits at Mr. D’s bedside, where she has taken roost. “I open my eyes and look up at the photos of what the Deuslers have done in this place—all that comedy and tragedy they’ve given to the community instead of each other.” Tess watches Mr. D’s painful suffering increase, until she can take it no more, and she offers him relief in the only way she knows how, finally giving the best and most painful performance of her young life.

“Canis Major” tells the story of twelve-year-old Rosie, whose family breeds Rottweilers as bodyguards. Rosie’s job is to feed live rabbits to the stud-dog Apollo and use a stopwatch to time how long it takes him to devour each rabbit. When Rosie’s teenage sister Vivvi becomes the third of three teenage girls to go missing, the neighborhood is on high alert, and the local grocer declares in church that, “ . . . we can’t let the shadows swallow our children.” Rosie takes this to heart, and with the aid of her protector Apollo, she is determined to bring her sister Vivvi safely home.

The stories “A New Kukla” and “White Rabbit” reveal the chronological growth of characters Historian Richard, his son Ollie, and Richard’s brother Bobby, as these two stories are set ten years apart. In “A New Kukla,” Richard’s social status causes him to lie to his Catholic wife’s family about his daughter by a previous marriage. Richard’s daughter isn’t allowed visitation, and this secret, along with the secret of Richard’s ongoing extramarital affair, reveals as much about society in the 1960s, as it does about Richard himself. Ten years later, in “White Rabbit,” Richard’s son, Ollie, is the troublemaker of his fourth-grade classroom. When Ollie is suspended from school, Uncle Bobby takes him to work, in order to help Richard keep the suspension secret from his wife. When Ollie vents his frustration by causing turmoil at Uncle Bobby’s office, Uncle Bobby takes him to a so-called meeting, which actually is a visit to the local brothel. Ollie learns firsthand that secrets and lies are a necessary part of life.

“Representing the Beast” opens in 1995, with ballerina-in-training Keiko watching the news, when she learns of the Kobe earthquake, in which her cousin Ayaka, a gifted ballerina, is killed. Keiko’s mother and aunt push and pressure Keiko to replace the more gifted Ayaka. Keiko’s health issues hinder her skill and practice, though she finds inspiration in the diaries of prodigious ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, whose “forte was representing the beast. That’s what people understood, a beast that channeled God.” Keiko finally pushes herself—physically, psychologically, emotionally—on bloodied feet, to give the best performance of her life, during a practice no one sees.

In “The Music She Will Never Hear,” Keiko has given up dancing, and her friend Jace has given up performing music, and both accompany friend Brad cross-country from one Phish concert to another. Richard reappears, again chasing history, this time into a mine, where Jace is his tour guide. Jace entertains the historian with facts and local tales, all the while believing people understand only what they allow themselves to see. “Sometimes you can learn everything you need to know just by checking a window, looking through it past your reflection into what you can’t see from any other angle at any other time.” Richard collapses while inside the mine, and Jace contacts his son, Ollie, who, now in his thirties, is even more jaded by his family history of secrets and lies.

Though each of the nine stories in this collection addresses the psychological and sometimes physical pain of grief and loss, we find glimmers of hope. This is perhaps no truer than in the final story “The Cliffs of Dover,” in which sixteen-year-old Cora is pushed into a pre-arranged marriage that ends with a funeral, leaving us with the hope that, even following death, one might find freedom.

This critical examination of the harm families sometimes do to one another—particularly to our young—also offers the promise of healing, if only we step back and examine how we hold on to one another, and perhaps more importantly, how we let go.