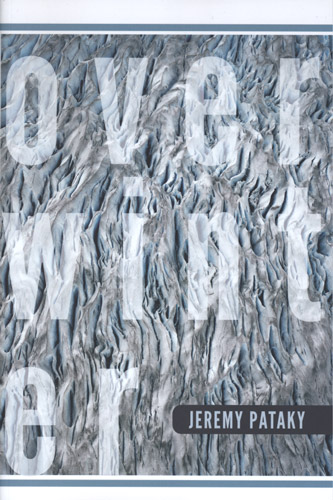

Overwinter, Jeremy Pataky’s debut poetry collection, examines the speaker’s isolation and solace in the vast, untamed nature of the Alaskan wilderness. Throughout the collection, the speaker spends his time between a developed city, with its electricity and human companionship, and the natural Alaskan landscape filled with its braided streams, unpredictable wildlife, and endless illusions of light and depth. Overwinter, Jeremy Pataky’s debut poetry collection, examines the speaker’s isolation and solace in the vast, untamed nature of the Alaskan wilderness. Throughout the collection, the speaker spends his time between a developed city, with its electricity and human companionship, and the natural Alaskan landscape filled with its braided streams, unpredictable wildlife, and endless illusions of light and depth.

There are deep currents of aloneness and loss threading themselves through Pataky’s poems, but rarely does the speaker seem lonely. He accepts, in what ways he can, the solitude of his existence in the wilderness. Yet nature breaks the silence of his thoughts. In “Antidote,” a creek seems to cure. Nature’s murmurings bring a therapeutic calm—a welcome intrusion—to the otherwise incessant silence of a man alone in the wild.

Pataky’s descriptions portray nature’s cyclical qualities. From the first poem, “Five Parts,” we are told “The life is made from five parts: / shelter, mountain, ground, lake, // and ash.” The poem, inspired by an epigraph by Nigel Peake, invites readers to think of destruction as an opportunity for new growth. Ash is a sign of fire, destruction, and decay, but perhaps it’s also an invitation for rebirth. Nature seems to care for itself independently:

The land is made of glacial flour

and fossilized rivers. The shelters

dissolve back into ground.Mountains deliver water to the lake.

The lake is new. It shrinks and grows.

The landscape is continuously changing and renewing itself, but not independently of human interference. In “Wood Heat,” we are reminded that we are “those who trim unseemly branches, / who edit for horizons, lake views.” We are subtly told that we require nature for our own wellbeing, despite our inclinations to tame it for our conveniences and greed.

With nature’s beauty also comes its illusions and unreliability. There is an eeriness depicted in “Fata Morgana,” which describes the ways in which light can play tricks on our eyes:

I return to a book about Arctic exploration, tricks of light traveling through unevenly tempered air, whole islands perceived, navigated toward, mapped, fled from, sought out tens of years later, the same illusion, just light . . .

Nature has its share of tricks and “problems.” Pataky also points out the lack of contrast in an Arctic landscape dominated by white snow and ice: “no opportunity for comparisons—a distant / polar bear, a nearby snowshoe hare.” We cannot always trust what we see, and can’t always predict the effects that wildlife will have on our lives. In “Steeped,” a bear swims to an island and bites holes in a family’s inflatable boat: “The family, asleep inside, / is stranded, and the animal / is gone when they wake.” Things are not always as they seem, and nature can often be unforgiving, both in its illusions and realities.

There is a sense of loss present throughout Overwinter, and frequent images of jet plains remind the reader just how vast and expansive the Alaskan wilderness truly is. If someone were to get lost, what are the odds of being recovered? This question is neither directly asked nor answered in the collection, but the descriptions of an immense and unreliable landscape seem to invite this speculation. More than once, we are introduced to the concept that the speaker has lost someone close. In “The Particulars of the Built Environment,” a villager watches overhead for a plane and next:

he gillnets the swum awe

of our homing instincts,

dragnetting sea vents, the soft

tissues of your body

which are, I imagine,

the brightest aquatic creatures

inside the opaque gut

of the ocean.

These lines suggest that someone has been recovered, but only after it is far too late. Later, in “How the Mistress, Distressed, Insinuated Herself Into Place” fire crews and helicopters search for someone until “traces time-bombed in time together.” The speaker clearly feels a loss and repeatedly returns to the creek for solace.

In the last poem of the collection “The Wild Dead,” readers are reintroduced to nature’s cyclical qualities. The speaker and a companion witness several animal corpses, “voledeath, hawkdeath, goatdeath,” while hiking on the ice. The speaker reflects:

Your arms bracket

small deaths, cubdeaths, avalanched and thawed.

Snow burial repealed a summer set on decomposition,

then autumn built itself

on the bones of unraveled bodies.

Throughout Overwinter, we are reminded that while loss is inevitable, matter is not finite. Destruction into ashes is an opportunity for growth. What is lost in nature becomes new again, “It shrinks and grows.”