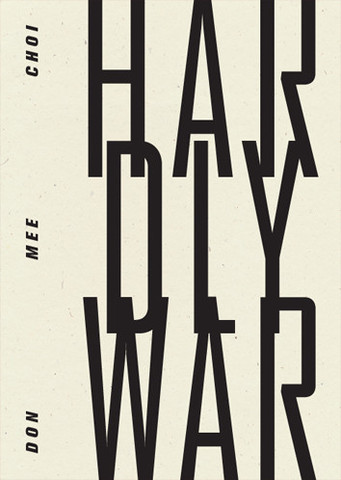

Race and Identity are two separate functions of description, but in our times, hardly. There is a war between nations, inside of nations, and ultimately inside of each individual. In the forthcoming Hardly War, Don Mee Choi details the interior of the life of a young girl in the middle of war. This is no mere reduction or retelling. The metaphor stands that we are all hardly adults. Perhaps hardly human. The complex war machine has turned us into THE BIG PICTURE and reduced us: “It was hardly war, the hardliest of wars. Hardly, hardly.” Race and Identity are two separate functions of description, but in our times, hardly. There is a war between nations, inside of nations, and ultimately inside of each individual. In the forthcoming Hardly War, Don Mee Choi details the interior of the life of a young girl in the middle of war. This is no mere reduction or retelling. The metaphor stands that we are all hardly adults. Perhaps hardly human. The complex war machine has turned us into THE BIG PICTURE and reduced us: “It was hardly war, the hardliest of wars. Hardly, hardly.”

The speaker’s father is poised with his camera, to capture the next hill. She seeks to show us that regardless of attention or thrill, there is always another hill to be mounted as man is not comfortable without art. The photographs that document the experience are only partly history. While the photographs are not playful, the demonstration of form has an attitude of playfulness about it. So much ‘partly, partly’ and ‘hardly, hardly’, because the BBC documents what is really history. Mass culture gets to decide who belongs on the sidelines, which often enough is the narrator:

I was narrowly narrator,

yet superbly so.

I wantonly resisted nothing in particular

yet superbly so

I was narrowly narrator.

This is the tale of reduction—how humans are turned from one form to another under pressure. Whether it be our dutiful poet, Choi, or the reporters trying to do their job for the BBC, or even myself in this review, who can choose to objectively see the past the way Choi saw most of the menu for the soldiers in “A Little Menu?”: “Wieners / Canned fruit / Crackers / Soluble coffee / Milk powder [ . . . ]” But then she poses the question to the generals, those in charge. What did their menu consist of? This poem rests right next to a photo of a few Koreans in the midst of smiling Americans, all appearing to be of a certain regal military persuasion.

Choi has sorted through her father’s pictures and has discovered a language. This language begins by stating that both ‘beauty’ and ‘ugly’ are the same as ‘nation.’ And she states continuously that she is a Gook, the slur that she has adopted for herself and every other traditionally garbed Korean in the nation. As if this isn’t bad enough, it detours into the more gruesome truth in the very next poem “Suicide Parade,” which states exactly how Napalm is made and how it clings to the skin and kills.

The middle section of poems is title “Purely Illustrative” and moves even further. The subject matter and content begins to dictate the form more and more. At this point, it becomes a little clearer that Choi is illustrating how the circumstances and pressure create the response. What more could her father do but to go out and document it? And while she found herself to be a narrow narrator, she had to write poems about the entire experience.

“History is hysterical. The-13th-child-also-says-it’s-terrifying. 13+3+3. 19=13. A modest, shared hallucination.” This is in regards to watching the plight and trauma of Americans in the film The Deer Hunter. If Hardly War can teach us anything, it is that perspective is everything. The ‘Illustrative’ portion of the poems is there as a guide and teacher.

In the final portion of the book “Hardly Opera,” Don Mee Choi is able to reflect on all of the photographs that her father took. As the photos are interspersed throughout the book of poems, it is easy to get a feel for what the writer’s vision and ideas are, but every knowledgeable readers knows that writers are allowing pieces to find their own voice as they go. This is certainly the case with this political work that is hardly a political work.

Throughout the book, there are also little jingles and music. This aids the playful development of the poems and the language and translation that Choi has created. The songs seem to pick up speed in the end with many exclamation points and numbers and general coded speak. Near the end Choi writes:

Shall we go out?

There’s an old gate O marvelous!

Taedong River O beautiful!

Angel’s pagoda O marvelous!

Shall we go out?

American soldiers are waving to us

We are wearing the same uniform