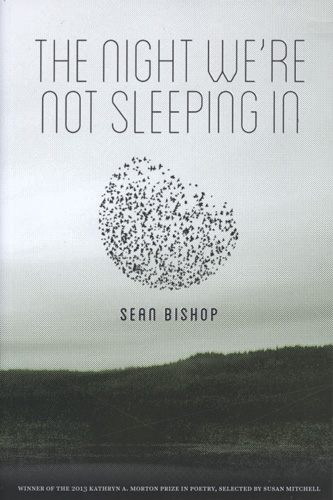

The Night We’re Not Sleeping In

The poems in Sean Bishop’s elegiac debut collection The Night We’re Not Sleeping In seethe with animosity—sometimes humorously, sometimes righteously—toward all manner of received wisdom about life, death, grief, and consolation. Selected by Susan Mitchell as the winner of the Kathryn A. Morton Prize for Poetry, the collection centers around the death of the speaker’s father, with several longer poetic sequences throughout the book’s four sections interrupting and elaborating on similarly turbulent themes. The poems in Sean Bishop’s elegiac debut collection The Night We’re Not Sleeping In seethe with animosity—sometimes humorously, sometimes righteously—toward all manner of received wisdom about life, death, grief, and consolation. Selected by Susan Mitchell as the winner of the Kathryn A. Morton Prize for Poetry, the collection centers around the death of the speaker’s father, with several longer poetic sequences throughout the book’s four sections interrupting and elaborating on similarly turbulent themes.

Section one features a sequence of dramatic monologues in which Bishop’s apocryphal version of the biblical Adam relates his fraught progress from new life to new loss. The second and fourth sections feature a series of seven dramatic monologues addressed to the reader, each entitled “Secret Fellow Sufferers.” The book’s third section consists solely of the sequence, “To Throw the Little Bones that Speak,” which takes its title from the I Ching and describes a topsy-turvy boat ride through a vernacular Hades. Characterized by brash musicality and quicksilver shifts in tone and diction, Bishop’s mordant and sobering poetry is more confrontational than confessional in its rendering of the evasions, posturing, and poignancy of grief and resentment.

In Bishop’s poem “Terms of Service,” which precedes the collection’s first section and introduces the insoluble dilemmas at the book’s core, life is imagined as a service provider using legalese to protect itself from being held liable for inevitable tragedies and disappointments. With its burlesquing of a non-poetic form, as well as its intricate use of rhyme and figurative language, “Terms of Service” showcases the collection’s tragicomic tension:

Furthermore should the signed’s father choke in his sleep,

should his brother spoon down a brown bottle of pills,

should his mother succumb to the village of tumors

thatching their damp huts inside her,the signed shall hold harmless said company

for adjusting the terms of the Family Plan.As a courtesy in such cases the company may reveal itself

through flocks of oddly colored birds that land

Much of what makes Bishop’s speakers absorbing is that they’re not the solace-seekers of typical elegy; rather, they are speakers who’ve slowly discovered how endless accumulation of experience and its attendant loss negates the possibility of lasting solace. Because of this discovery, his speakers value rebellion and struggle rather than putting stock in faith and resignation. Bishop’s speaker begins the third poem in the “Secret Fellow Sufferers” sequence with a simile describing the stark beauty that suffering can draw out: “once more our old wounds / like milkweed pods have opened, and we’re lovely again // as our winces break off in the wind.” The speaker then goes on to stress his fundamental belief that life is an advance rather than a retreat:

[ . . . ] We must identify

the ones of us who’ve lived whole yearswith a wasp in their mouths, and our enemies

who believe the trick to ascendingto a bright hereafter is to tread so lightly

they float away—

Such belief also colors the monologues of Bishop’s Adam. In one of the collection’s finest marriages of conceit, tone, and diction, “Adam Home from the Wars,” Adam mocks the very possibility of lasting solace:

Yes, when the orchard’s dolled up in pastel

and the finches scrawl cursive across the sky

and the big moon sags like a tit o’er the meadows

I’ll trade in my Glock for a pocket of dew.

Perhaps the most subtle yet revealing poem about the speaker’s fraught relationship with his father is “At the Optometrist’s I Almost Remember a Story I’ve Almost Remembered Before.” The poem’s perfectly-paced collusion between image and incident creates an unsettling account of trauma’s psychic legacy. After another optometrist informs the speaker about a tear in his lens that was likely caused by childhood trauma, the speaker reflects on the image this reminder calls up. Ingeniously, Bishop begins the poem with a simple, striking description of that image:

My father had one thumbnail like a fossil—

scalloped, marbled yellow, a slug print trapped in lime.“Canning factory,” the story went. “Conveyor belt.”

Bishop then spends the rest of the poem slowly turning this maimed thumb into a symbol of dominance and a cause for rebellion. By having the speaker fail to make explicit the connection between the torn lens and the possible abuse, Bishop is able to deliver a fascinating insight about the difficulty people have when trying to classify personal tribulations using facile categories:

[ . . . ] I don’t remember

any trauma. What I dois my father: how when he was ashamed,

or sorry, he’d tuck his mangled nail into his palm

With The Night We’re Not Sleeping In, Bishop has created a monument to internal conflict and shown that disentangling the distortions of grief from the essential animosities of the human condition is the project of a lifetime. Bishop’s technical resourcefulness and prying imagination have united to create a knotty and generous collection in which personal character is subjected to the crucible of grief and loss.