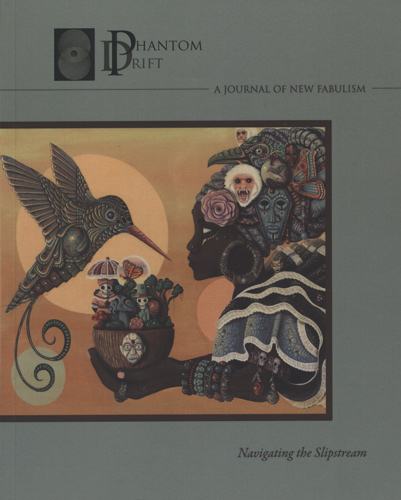

Phantom Drift – Fall 2015

Phantom Drift is an annual journal of slipstream writing: fiction, nonfiction and poetry which experiment with fantastical and realist elements. The work published in Issue 5, Navigating the Slipstream, is unapologetic and unseats us from our perceptions of reality. Phantom Drift is an annual journal of slipstream writing: fiction, nonfiction and poetry which experiment with fantastical and realist elements. The work published in Issue 5, Navigating the Slipstream, is unapologetic and unseats us from our perceptions of reality.

Maggie Nye’s story “I Am Called Cain” subverts the Cain and Abel tale by redefining words. When Abel slaughters a lamb, Cain hears, “a sound [he] called prayer.” In Nye’s story, death is a prayer which makes Cain’s actions in killing his brother become more understandable. Nye’s prose relies on that understanding, and her first person narration is honest and innocent. Cain’s character believes having a “brother would mean that if he fed himself, my belly would also grow full.” He does not apologize for killing Abel, and Nye does not apologize for twisting our definitions of words.

Continuing the Biblical route, Laura Bernstein-Machlay’s “Walking Jesus” is unapologetically irreverent. The narrator had to put Jesus on a leash. The poem speaks directly to the reader and still catches us unaware. In the middle of the poem, Jesus runs after a neighbor, “his finger all alit with prophecy / and Wham! An SUV / to the side of the head.” They bury him, but next morning he’s up / nosing through the garbage.” With wit and humor, Bernstein-Machlay’s poem is like a car crash, or an SUV to the head. There’s no anticipating or preparing for it.

Anna Lea Jancewicz has her own irreverence in her story “Vaginal Disturbances.” Jancewicz refuses to apologize for her focus on cisgender women’s bodies. Rita, under the distress of parenting young children, expels a long-lost Dungeons & Dragons miniature out of her vagina. In reclaiming her D&D character, she reclaims her life. Jancewicz revels in the shock and hilarity of Rita’s liberal use of curse words and a character who tells her husband during sex, “So you think vaginas are disgusting? Are you gay?” With no restrictions on her language, she writes about women’s authority as women and artists. However, Jancewicz equates woman with vagina, which excludes trans people and denies them the right to authority and art.

Peter Granbois’s essay “Navigating the Slipstream” is another piece which unfortunately is not inclusive of all. Grandbois argues that slipstream fiction, not realism, creates stories that linger. And though Granbois pulls evidence from artists, poets and fiction writers, his evidence comes from almost exclusively male figures. His perspective stays in Western traditions, with only a nod that in “Latin American, Asian, African or Eastern European literature—you find ‘realism’ is no longer the dominant form.” Grandbois does not name the Latin American tradition of magical realism, or highlight the female voices in this genre. The essay disappoints with how Western and masculine it is. I wished for an apology.

“Dance Spider Dance” by Giovanni De Feo, does not disappoint. The premise begins as a fairy tale: Ida, an orphan girl, is ugly with the face of the moon. To win the love of a nobleman, she seeks Tarantula, the White Widow spider, whose kiss drives women mad and they dance to their deaths. De Feo’s story explores lesbianism and features almost exclusively female characters. What Ida wants isn’t the nobleman’s love, but to prove she has worth beyond her appearance. Ida seeks the power to stand on her own, even at the cost of her sanity and her life. And in the process, Tarantula becomes like Ida’s lover where, even after bestowing her kiss, Tarantula dances with Ida and “With green lips she kissed the girl’s neck” and the two make love. De Feo dashes expectations of a heterosexual fairytale in favor of a female driven narrative where no one apologizes for her choices or appearance.

Trevor Tingle plays with fairytales in his poem “Will We Ever Find Dark Matter.” The answer is yes: dark matter is all around us. The ordinary becomes bizarre when “bare feet take note of bread crumbs on our floor” and stories of Hansel and Gretel surface. What was once familiar takes on a magical sinister tone. Tingle ends his poem commenting that “Our lives are fairytales; everything works out / just a little more brutally than expected.” Tingle blends magic with realism and the result is a jarring reminder of the dark beautiful world in which we live.

The authors featured in Issue 5 of Phantom Drift: Navigating the Slipstream toe the line between fantasy and realism, and cross the line of appropriate and expected. In a genre where experimentation and strong storytelling are mixed, there are no apologies for shaking us from the comfort of reality to take another look at the familiar.

[www.phantomdrift.org]