Eleven Eleven – 2017

Issue 23 is notable for a number of reasons, including the departure of longtime Faculty Editor Hugh Behm-Steinberg—and what an exit it is. The current issue of Eleven Eleven (8” x 8” if you’re curious) is large, daring, fun, and occasionally a hot mess. Consistency is hard to achieve with student-run publications; editors are cycling out each year as new staff comes whirling in, and errors occasionally slip through the cracks. In most cases, the missed edits are those spellcheck would ignore—e.g. a “bowl” movement or a phrase in Latin “hat” translates—but others, like “Dega’s painting” (it should be Degas’ or Degas’s), remain unchanged too, unfortunate blemishes on otherwise pristine pages. Viewed separately, these missed edits are minor blips, but piled together (and there are plenty more), the issue is cheapened, and even the best pieces, impeccably written and edited as they may be, are done a disservice.

Issue 23 is notable for a number of reasons, including the departure of longtime Faculty Editor Hugh Behm-Steinberg—and what an exit it is. The current issue of Eleven Eleven (8” x 8” if you’re curious) is large, daring, fun, and occasionally a hot mess. Consistency is hard to achieve with student-run publications; editors are cycling out each year as new staff comes whirling in, and errors occasionally slip through the cracks. In most cases, the missed edits are those spellcheck would ignore—e.g. a “bowl” movement or a phrase in Latin “hat” translates—but others, like “Dega’s painting” (it should be Degas’ or Degas’s), remain unchanged too, unfortunate blemishes on otherwise pristine pages. Viewed separately, these missed edits are minor blips, but piled together (and there are plenty more), the issue is cheapened, and even the best pieces, impeccably written and edited as they may be, are done a disservice.

Editorial sniping aside, there is plenty to love in the issue. Sara Rauch’s “Esther” follows two young girls as they hitchhike to a music festival, in search of various highs and freedom, but certainly not the baby girl who is dropped into their laps. At one point, Calla, the supposedly more responsible, reserved half of the duo is tripping on mushrooms. “A whisper of new language,” Rauch writes, “susurrations fluttering her chest like wings, like starlight, like two heartbeats, like chaos being born.”

Other memorable moments are the decline of a parent in Margo Barnes’s “A Gift from My Father,” Jacques Drillon’s hotel hallway tryst in “The Hallway,” the “wet little rooms in my head” sam sax describes in “Klonopin,” the moving father-daughter tête-à-tête in Joshua Flowers’s “Sneaking Out for a Cigarette,” the pull Elizabeth Hall feels to Huntington Beach in “Far and Wide,” the oddly charming protagonist of Vardges Davtyan’s “I’m Jack. Jack in the Cab (A Collection of Notes),” the green wound in G.C. Waldrep’s “At Intervals I Am Complete As Valence, Gift, a Prayer,” and the tragic charisma of Maarja Kangro’s writing, taken from The Glass Child and translated from the Estonian by Adam Cullen. She writes:

I had already seen the tiny being wriggling its arms and legs on a regular ultrasound machine. A fuzzy little white aquatic creature against a black background. The amplified heartbeats had been picked up several times already, sounding like a speeding train coming through a transistor radio. Wild and solemn.

The author and artist interviews are also intriguing. Short story master craftsman George Saunders deftly extricates himself from an awkward follow-up question—“to whom is [Lincoln in the Bardo] not written?”—replying with, “When I write I am really hoping to exclude nobody.” In his discussion with Audrey T. Williams, Peter S. Beagle recalls his time studying under Frank O’Connor, who loathed fantasy. Upon reading Beagle’s “Come Lady Death,” O’Connor remarked, “This is a beautifully written story. I don’t like it.” The piece was ultimately published in The Atlantic and won an O. Henry Award.

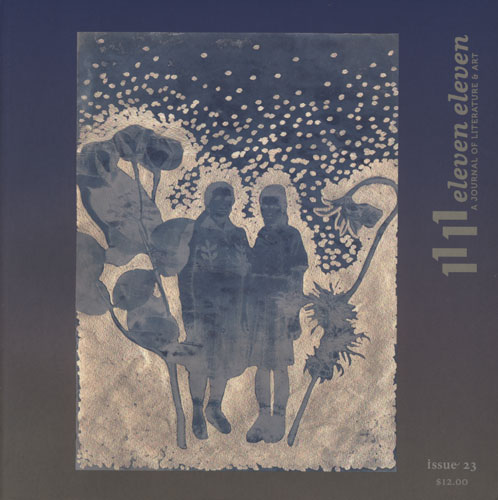

Later in the journal, cover artist Monica Chulewicz discusses her diagnosis of Mitochondrial Disease, its impact on her work, and her desire to grow her art into larger, public spaces. Her cyanotypes, and reliefs by Hyeyoung Shin, are some of the visual bright spots in the issue.

The journal’s oddest inclusion is “Wristcutters” by Borja Cabada, which reads like a Tommy Wiseau screenplay, melodramatic and stilted to the point of absurdity. “But I never stopped loving you, babe,” Cabada writes. “How could I ever? You are my life, Alice.” The moment is powerfully evocative of The Room, particularly the scene in which Johnny raises his fists in anguish, yelling, “You are tearing me apart, Lisa!” To take the piece seriously is to make it unreadable, but indulging in the (probably unintentional) humor makes it oddly accessible. Notably, Cabada’s plot loosely mirrors that of a similarly titled piece of art—the quirky black comedy Wristcutters: A Love Story, which was based on Etgar Keret’s novella Kneller’s Happy Campers.

Issue 23 of Eleven Eleven is far from perfect, but the journal’s openness to experimentation and risk is admirable, as are many of the pieces themselves. A few changes would be welcome: the announcements of forthcoming collections, placed below a number of poems, would be better located in the Contributors’ Notes section, and it would be helpful for the Table of Contents to distinguish between fiction and nonfiction. Beyond these minor gripes, though (and sure, the larger ones mentioned above), Issue 23 is ambitious, inclusive, and unafraid. It is the kind of publication one can get lost in, despite the bruises and small grievances. Though he is leaving, one hopes the incoming staff will follow the advice of faculty editor Hugh Behm-Steinberg—as quoted in the introduction—and “make the best choices ‘because that’s classy.’”

[www.cca.edu/academics/graduate/writing/eleven-eleven]