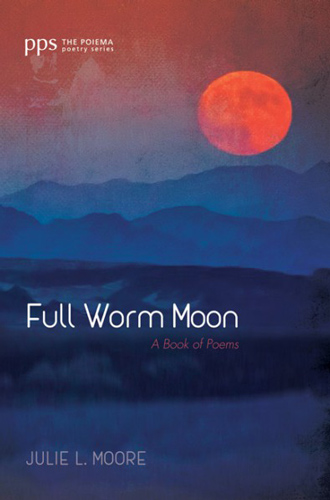

Full Worm Moon

How does one write rejection? Specifically, the violence or indifference of a spouse? One makes a decision to be with a particular person, like be with them in everything—they say, yes—but the contents of that pact disintegrate, sometimes going up in flames quickly, and other times burning slowly and carried off, piece-by-piece, with the wind.

How does one write rejection? Specifically, the violence or indifference of a spouse? One makes a decision to be with a particular person, like be with them in everything—they say, yes—but the contents of that pact disintegrate, sometimes going up in flames quickly, and other times burning slowly and carried off, piece-by-piece, with the wind.

Honestly, the longer I am a poet and a human, the more I realize how completely we break under the pressure of these unexpected relational turns and the rejection they imply, of sometimes, our whole personhood. And who can blame us? No matter how independent or resilient we fancy ourselves to be, we’re just not strong enough to bear them entirely alone.

Julie L. Moore culls the depths of this unbearable rejection in Full Worm Moon within the context of marital infidelity and divorce. While the topic may not be fresh, it is always relevant and worth examining through another lens, another personal perspective.

Writing about divorce is tricky. Nearly half of Americans have been there, and it’s hard to say whether the falling divorce rate (since about the 80s) is a good or bad thing because divorce depends on complex factors that may indicate it’s better to walk away from a relationship than remain. In any case, I think we can all agree that rejection is always part of the equation. And it is the part of separation—no matter how necessary—that breeds emotional horror and leaves behind seemingly unending questions about our individual self-worth.

Moore asks in “Once”:

What trickles over the stoop now,

what streams in the tributaryfrom a puddle by the door,

from pink impatiens, doused?Rocking chairs, while balustrade,

her,all beneath mist high above the porch,

where ferns suspendtheir thirst for summer,

for that husbandsoaking begonias in their bed, once.

In writing lines like these, Moore understands her own questions of self-worth in the wake of rejection, and bravely admits intense longing and vulnerability. This bravery is strengthened in “Nightmare,” as the speaker claims:

She sees their counselor, confesses.

She wants to hit herself, slice her wrists.

The counselor says she must not be so desperate

for her husband’s love. She must let him go.

And braver still in “PTSD”: “The counselor tells the wife to write through fear, / mine her journal’s thirty-thousand words / for the hardest rocks to remove” and:

The therapist also says to revise

the script of her recurring nightmare,

take the six-foot figure of her husband

barreling into her as she tries to hold

every door, laughing at her when she says,

You are scaring me (the predictable sequence

inspired by her marriage’s last day),& turn it into a kitten,

reduce his ridicule to one meager

meow.

But any intelligent reader knows that none of this can be reduced to a meager meow. The speaker’s memory of her husband’s “chest, pushing / through doors, plowing into her, his hands / threshing the phone / from her fingers / trying to dial 9-1-1” (“Barley Moon”) won’t be easily minimized or erased from her memory. Neither will his secret “electric glances with another woman” (“Baseball”) about whom he warns her “if you won’t let me / be friends with her, / I’m leaving you” in a Mother’s Day card (“Four days after Mother’s Day”).

Moore is telling us a narrative that some might prefer to forget or fester over secretly, but she has bravely chosen poetry to thresh it out. At 121 pages, her book almost reads more like an anthology of this single poet’s voice. She has handed her reader a whole history of this single rejection in three parts: “Full Thunder Moon,” “Aftershock,” and “This Is The Landscape Left.” Each section feels as though it carries a narrative all its own; in fact, each section could have been a separate book and I read it as such. I made my way slowly through each section, letting the first, “Full Thunder Moon,” roll waves of pain and disappointment over me as though a lunar season refusing to let go, mapping the longevity of a marriage that saps the life out of the speaker, and before she realizes it, she’s been at this one destination far too long (a feeling I know too well).

But it is “Aftershock,” the second section, that really begins to explore the internality of the speaker—a new destination worth equal lingering. In the book’s title poem, Moore writes:

this moon

announces, in all its fullness, worms

stirring in earth’s softening center;

sap thawing in maples;

snow dissolving by day, crisping by night;

& crow calls converting from haunting ballads

to heralding hymns. A robin appears,

throwing off the pine cloak it hid behind

all winter like a god hard to find, hard to hear,

maybe hard of hearing in the ruckus

wind made as it bayed across plains

& yowled down valleys, hard to see in ice

suffocating once-tasseled fields, pinecone & bayberry,

numbing perhaps even wings,

rendering the soft touch this moon offers

almost senseless.

This poem strikes me as ushering in a new season, a new journey of the heart, in which the speaker begins to look inside and discover self again. The poems enter the speaker’s emotional condition from a variety of angles that consider scenes from childhood, classical history, the speaker’s relationship to other members of her family, her Christian faith, a Midwestern landscape—all of it suggesting how her mind and body reel with the aftershock of a failed marriage, including some joys, however temporary.

Mule deer gather

in the Strawberry Valley

feeding as the moon

in its white robe

nudges the sun, drowsing

along the horizon, to bed.The animals allow

my daughter & me

to come close, [ . . . ]

The portraits, like ones from “Coming Close” quoted above, are intimate and benedictory . . . and sometimes slightly humorous, like these lines found in “Morning Prayer”: “God bless the cow in the field that sneezes. / God the dog who hears the sneeze, // then lunges at play toward the fence [ . . . ].

They ask the reader to recall that there are still landscapes and relationships unmolested by turmoil as in “There Is No Violence Here”:

What do birches teach us,

their yellow leaves long ago

having tumbled to the ground

exposing limbs to whatever raw

& consequential wind

may come?

And the poem answers in the last two lines: “Lean in. Listen to the soft / cellular breath tell you what it can.”

The final section of this book “This Is The Landscape Left,” speaks exactly of that: what remains. Rejection is a painful and shocking discovery, but if one survives its initial pangs, the world become a brand-new space to roam. In life there is always opportunities for beginning anew, not better expressed than in the first poem of this final act (also possibly my favorite poem in the book) “Objects in the Mirror Are Closer Than They Appear,” which ends:

This harvest moon

doesn’t seem deceived.

It has the gift of distance.

It gazes into my neighbor’s pond,

gleaming like one enamored

with her own reflection,

its alabaster surface so close

I want to lower my hand

into the black water & swirl

the image till it loses all sense

of proportion, so when I leave,

light will drip from my fingertips.

And there, reader, I leave you, with some sense of hope—if only the hope offered of poetry, which I think is necessary enough.

Light dripping from fingertips. Moore’s poems take on a variety of poetic forms, all of which lend themselves beautifully to the moon’s reflection on a watery surface. Those satisfying moments that keep one going through the darkest hour of the soul.