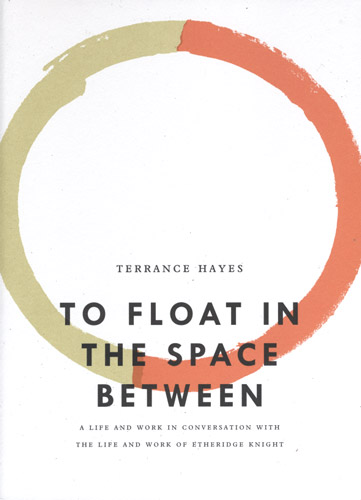

To Float in the Space Between

A Life and Work in Conversation with the Life and Work of Etheridge Knight

Terrance Hayes

September 2018

Cody Lee

I was nervous going into this book. I imagined a comparison between two poets to be full of abstruse information on cadence and meter, et cetera. To Float in the Space Between is indeed a comparison between the author, Terrance Hayes, and the late “prison poet,” Etheridge Knight; however, at no point in time does Hayes leave the reader out in the storm. He invites us inside, shares a cigarette, and lets us borrow his skin for a couple hundred pages.

I was nervous going into this book. I imagined a comparison between two poets to be full of abstruse information on cadence and meter, et cetera. To Float in the Space Between is indeed a comparison between the author, Terrance Hayes, and the late “prison poet,” Etheridge Knight; however, at no point in time does Hayes leave the reader out in the storm. He invites us inside, shares a cigarette, and lets us borrow his skin for a couple hundred pages.

The book was published by Wave Books, an independent poetry press based in Seattle, Washington. That being said, I wouldn’t consider To Float in the Space Between “poetry.” It does contain a handful of poems, but it’s more of a memoir, or a coming-of-age tale. Hayes makes mention of the Bildungsroman, and how in poetry, there’s no comparable concept. It may be too soon to tell, but this could be the birth of a new genre.

The fact that To Float “is not a biography” appears more than once. The author wants everyone to know that he did not do the proper research on Knight to deem it an official biography; nevertheless, if we were left unwarned, the amount of research included could qualify for such a title. Hayes visits and talks with Knight’s sister, Eunice, and a plethora of his contemporaries and former students. He analyzes Knight’s poems with x-ray vision, and incorporates old photos, examined just as thoroughly. The research is there. It seems as if Hayes holds Knight in such high regard that no matter how many people are tracked down and interviewed, it will never be enough.

After reading Knight’s poems, I can appreciate Hayes’s fascination with the man. The book starts with and revolves around “The Idea of Ancestry,” in which Knight lay in his cell, staring at the forty-seven pictures of his family taped to the wall. At the end of the poem, he says: “I am all of them, they are all of me, I am me, they are thee, and I have no children to float in the space between.”

The entire collection plays with the notion of oneness. Even the references that Hayes chooses are so far apart but fit perfectly together. In a span of two pages, we read about Don Draper, Jay-Z and Beyoncé, William Gass, Susan Stewart, Deborah de Robertis, Gustave Courbet, and Flannery O’Connor.

On page 98, Hayes quotes Wisława Szymborska:

Whether you like it or not,

your genes have a political past

your skin, a political cast,

your eyes, a political slant.

To Float in the Space Between discusses oneness, yes, but it also talks about blackness (which, at this point, is nearly the opposite of oneness); however, it does so in a way reminiscent of Szymborska’s poem: even if Hayes chose to exclude race, someone, somewhere would have felt obligated to point it out. So, the book exhibits this wonderful, prescient candor like B-Rabbit in the final battle in 8 Mile. It’s as if he’s saying, “Sure, I’m black. What’s the difference?” And the great thing about it is that this underlying question isn’t rhetorical, but proof of a genuine interest on how and if race matters.

This especially comes across when he details his experience at Robert Bly’s Great Mother Conference, where:

there were lots of mostly old men with beards, lots of mostly old women without bras, a few hippies with PhDs. But there was no television, no Internet, no easy escape route to town, and minus [him], no black folk.

Hayes then ruminates on Cave Canem, another writing community, but instead, for black people. He compares the two, calling them both “paradoxically open and closed” communities. (This makes me think of how closed-minded most men and women that call themselves “progressive” actually are.) Hayes asks his audience: “How should one balance the inclusiveness and exclusiveness of such spaces? Who should guard this balance, who should bridge it?” Since he is asking “who should bridge it,” rather than “should it be bridged,” perhaps Hayes already knows the answer to the question that he never, blatantly, asked: “Q: Does race matter?” “A: No.”

Speaking of “no,” here is an Emily Dickinson quote featured in the collection: “Don’t you know that ‘No’ is the wildest word we consign to Language?” In relation to the aforementioned Q&A, I would have to say that this is a fair assessment.

To Float in the Space Between is simply amazing. It’s an investigation of Hayes’s family tree, a time-lapse of one poet’s bloom, and an homage to the seed(s) that started it all.