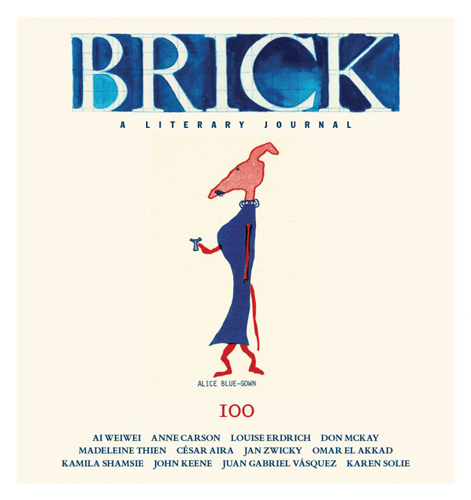

Brick – Winter 2018

Brick’s 100th issue celebrates forty years of nonfiction. An international journal published out of Toronto, Brick “prizes the personal voice and celebrates life, art, and the written word.” In issue 100, the authors look out into the world, to literature, to poetry and to nature for inspiration, while grounding their insights in the personal. Brick is a love letter to our artistic influences.

Brick’s 100th issue celebrates forty years of nonfiction. An international journal published out of Toronto, Brick “prizes the personal voice and celebrates life, art, and the written word.” In issue 100, the authors look out into the world, to literature, to poetry and to nature for inspiration, while grounding their insights in the personal. Brick is a love letter to our artistic influences.

“Halfon, Boy” by Eduardo Halfon, translated from the Spanish by Anne McLean, is a multi-layered love letter. Halfon’s piece begins as a letter to his unborn child, Leo, full of his hopes and fears of impending fatherhood. Amidst this intimate exchange, Williams Carlos Williams bubbles to the top. Halfon is translating Williams while his wife is pregnant, and the essay becomes a love letter to translation and a homage to Williams—a man who stumbled into reading, writing, and translating, the same way Halfon stumbles into fatherhood. “I wonder, Leo, if there might not be a connection between the process of becoming a father and that of becoming a translator.” Halfon mines wonder and exploration alongside his more concrete literary inspirations.

Sue Sinclair comes to terms with climate change in her essay “Poetry in the Age of Consequences.” Sinclair finds dead starfish on the beach and panics because she is experiencing a pinprick into the future of a world fully engulfed in climate change. This distress brings her out of years of numbness and into a strange kind of relief. She is only able to explain her emotions through poetry: “as a poet, I have to wonder what [poetry] has to offer, how it can help me to shift out of denial and [ . . . ] support me as I move deeper into the work of mourning [the planet].” Sinclair further pays reverence to poetry as her artistic influence, moving from the importance of poetry as an art, to the importance of specific poems that guide her towards new definitions of hope for the future.

Brick’s heart, its literal center piece, is a collection of short essays where authors consider why they write. What is the mortar of their writing life? For Garth Greenwell, his mortar is choosing to be a high school teacher rather than remain in academia. Only through teaching did he find life in his poetry and fiction: “The poems I was writing [as a teacher] were more attentive to the exterior world. [ . . . ] Human beings began to appear in them [ . . . ]. They started to tell stories.” Karen Solie also acknowledges her artistic influences, citing everything from her childhood books to her poetry courses in college. Her essay meshes exterior knowledge of etymology, poetry, and the literal physical mortar of bricklayers, with her personal experience as a reader, as a sister, and as a writer. Brick’s authors look outside themselves to better understand and present their work.

At times, Brick’s interest in artistic and outside influences can be inaccessible. “Poetry and Meaninglessness Part IV of IV: Why Meaning Matters” by Jan Zwicky concludes a four-part piece on meaning and poetry on seeing the world as a complex whole instead of individual parts. Even with a quick summary of each of the previous three installments at the beginning of the essay, Zwicky’s piece is difficult to follow. Her argument hinges on the “gestalt phenomenon” an idea that must be intuited from context because it is never quite explained. “Our experience of meaning is not fundamentally linguistic either in structure or in content: it is a quasi-perceptual gestalt phenomenon.” Despite a sparing use of the first person, Zwicky’s essay remains inaccessible. She references poets and outside influences without providing enough context for a reader to follow her thinking. This academic language and confusion is, however, a rarity in Brick’s pages.

Brick is incredibly concrete. Yet, it is an homage to what could easily become trite abstractions: art, nature, and literary influences. Each author has a voice that is physically present in their work, their words remaining grounded through their ability to weld their artistic influence with their personal experience.

[www.brickmag.com]