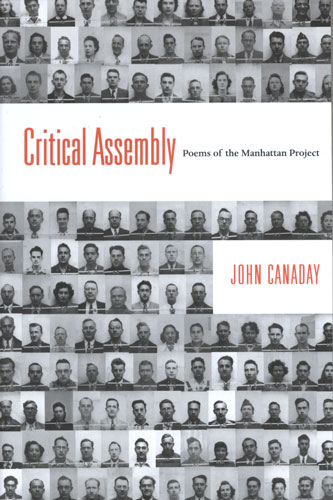

Critical Assembly

John Canaday’s newest book of poetry, Critical Assembly: Poems of the Manhattan Project, easily reads like a story about an era of American history that impacted the entire world. The Manhattan Project, code name for creation of atomic bombs during World War II, referred to the New York City borough where the project’s headquarters were located. The bombs, however, were assembled in New Mexico at the Los Alamos Laboratory and tested in a desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1945.

John Canaday’s newest book of poetry, Critical Assembly: Poems of the Manhattan Project, easily reads like a story about an era of American history that impacted the entire world. The Manhattan Project, code name for creation of atomic bombs during World War II, referred to the New York City borough where the project’s headquarters were located. The bombs, however, were assembled in New Mexico at the Los Alamos Laboratory and tested in a desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1945.

Each poem in Critical Assembly is titled with the name of a person involved in the project, either directly or peripherally. In some instances, Canaday incorporated a person’s actual writings into poems, and in other cases he “invented voices based on only scraps and hints” found during his decades of research for this and, I presume, for his nonfiction book The Nuclear Muse: Literature, Physics, and the First Atomic Bombs.

Canaday writes in the voices of key people like J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, and the perhaps lesser known Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, who, according to Canaday’s Biographical Notes, “drafted, and convinced [Albert] Einstein to sign, the letter that initiated the US government’s interest in nuclear weapons.”

But a slew of other individuals are included. The poem titled “Robert Serber: Physicist; Diffusion Theory Group leader” pretty much sets the tone for the feelings of those gathered in New Mexico:

When Oppie’s first recruits arrived in March,

few knew what we were working on. Rumors

stitched bits and pieces of the facts to pure

conjecture: radium-laced poison gas,

electric rockets, windshield-wiper blades

for submarines.

Several scientists questioned the end result of their assignments. Geneticist and former physicist Max Delbrück wonders:

If metaphors

for subatomic processes

were hard to come by—or too easy—

how could we describe the chaos

going on inside us?

Even Einstein questioned:

Perhaps

God has designed the world as I have thought,

and firing neutrons at the nuclei

of heavy atoms is like shooting birdsat night. But if I’m wrong, my data old?

Peer de Silva, Head of G-2, Los Alamos, speculates: “What’s / most vital to these forty-eight / United States?”

Canaday devotes several poems to the feisty Kitty Oppenheimer, Robert’s first wife. In her voice:

Now morning sickness is the proof of love—

I’m sick to half past death of proving it.

[ . . . ] but I’d go mad not knowing if he sees

the beauty he once said he saw in me.

Or am I what they say: an aging bitch

whose gotten knocked up one too many times?

The physicist Chien-Shiung Wu’s poem contains these lines:

Memos choke my room.

Stacked calculations mock me

with mute paper tongues.[ . . . ] Under unstained steel

skin—crisp, featureless—a warm

uranium heart.

Follow that with her biographical note: “Her experimental work confirmed the theoretical arguments of two colleagues on the invalidity of the principle of conservation of parity.” Sounds great, except, “Her colleagues were awarded a Nobel Prize in Physics, for which Wu was overlooked.”

Surely such a book would be lacking without a spy, and here’s where “Klaus Fuchs, Physicist, Soviet spy,” comes in:

I bridge

two headlands

smudged

by fog

invisible

to one another

though each

rocky footing

holds up

half of me

In the Notes on Poems section of Critical Assembly, we learn even more behind the scenes information, including notes that Fuchs’s older sister “committed suicide by throwing herself in front of a train to escape arrest for communist activities,” and his mother “committed suicide by drinking hydrochloric acid.”

But lighter moments are portrayed. Electronics group leader Willy Higinbotham was an accordionist. During a movie the crew is watching, “brittle film stock” snaps: “The masses rumble, restless, threaten thunder, / demand I man my stomach Steinway. / I wheeze. I moan. They stomp and clap.”

Of course, J. Robert Oppenheimer also has his say, more than once. Here’s a piercing example:

After the first flash, white as scalding milk,

blanched eyes dim in their sockets & grope toward

mortal sight, mere fire roiling in charred air.

[ . . . ] A botched shape slowly stands& roars. Its red breath reeks of burnt sand. Sage

ignites. Birds fall in flames.[ . . . ] My tongue is black

with ash.

Critical Assembly: Poems of the Manhattan Project is an important book for a glimpse into the public and personal lives of people involved in America’s first atomic bomb test. In the person of Robert Serber, Canaday writes these lines, which I’ll leave you with:

Who would have thought mere words—so technical

and flat the workmen never blinked—could sketch

the pattern of a star to singe the earth?