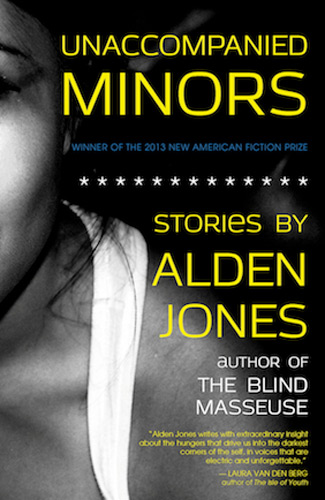

Unaccompanied Minors

Unaccompanied Minors, winner of the New American Fiction Prize in 2013, is a slim volume of seven short stories about young adults facing teenage pregnancy, homelessness, prostitution, the death of a child on his babysitter’s watch, and so on. “Shelter,” the first story in the book, is an odd choice for an opening, in that the story largely relies on the limited shock value of having homeless teenagers for its protagonists. Reminiscent of Dorothy Allison’s project to represent the lives of young poor women from the South, Jones’s story is less angry, but similarly features young characters who hide their vulnerability behind tough facades and speech that is likewise patina’d with derogatory slang. Unaccompanied Minors, winner of the New American Fiction Prize in 2013, is a slim volume of seven short stories about young adults facing teenage pregnancy, homelessness, prostitution, the death of a child on his babysitter’s watch, and so on. “Shelter,” the first story in the book, is an odd choice for an opening, in that the story largely relies on the limited shock value of having homeless teenagers for its protagonists. Reminiscent of Dorothy Allison’s project to represent the lives of young poor women from the South, Jones’s story is less angry, but similarly features young characters who hide their vulnerability behind tough facades and speech that is likewise patina’d with derogatory slang.

The stories get better from there, though, and “Freaks” is a standout. Told from the second person point of view, the story focuses on a narrator who develops a skin condition—scales that periodically grow on one of her arms—that she begins to view as a positive manifestation of her difference from her peers, and the story manages to feel affirming even as it resists obvious affirmation.

“You,” a bereaved mother accuses the narrator-you at the end. “You think you see something no one else sees?” It’s an interesting moment, because, truly, the characters in this book don’t; they’re misfits and miscreants, but they also tend to be refreshingly self-aware. Issues of privilege are treated with complexity and sensitivity through stories that use missionary work and volunteering as their backdrops. The prostitutes in the penultimate “Sin City” are richly characterized, and the story’s final dark move feels unexpected but is sure to be memorable.

Furthermore, “Sin City” and “Flee” nicely counterpoint each other as the last two stories in the book as one story ends with the narrator choosing selfish gratification over family, while the other ends with the narrator forgoing gratification in favor of compassion, having decided “it was time to grow up.” in the world of Unaccompanied Minors, the characters are capable of choosing to be moral or not, and the unpredictability of their decisions only makes the book feel more satisfyingly realistic.

The plots of Jones’s stories tend to be simple—two homeless girls ditch a shelter for the night, or a girl’s Big Sisters charge loses a tooth, for example—but the stories are memorable nonetheless, and they become longer and the characters more complex as the book progresses. These are hard luck, hard knocks stories in which happy endings aren’t guaranteed, in which characters want and go on wanting. “Flee,” the book’s final story, opens, “We were always hungry, all of us. We fought over food. We tried to trick each other out of fair shares. Eliot said he had never seen anything like it.” Hunger—for food, acceptance, love—drives the characters to act for and against their own best interests in stories that span from the United States to Puerto Rico.