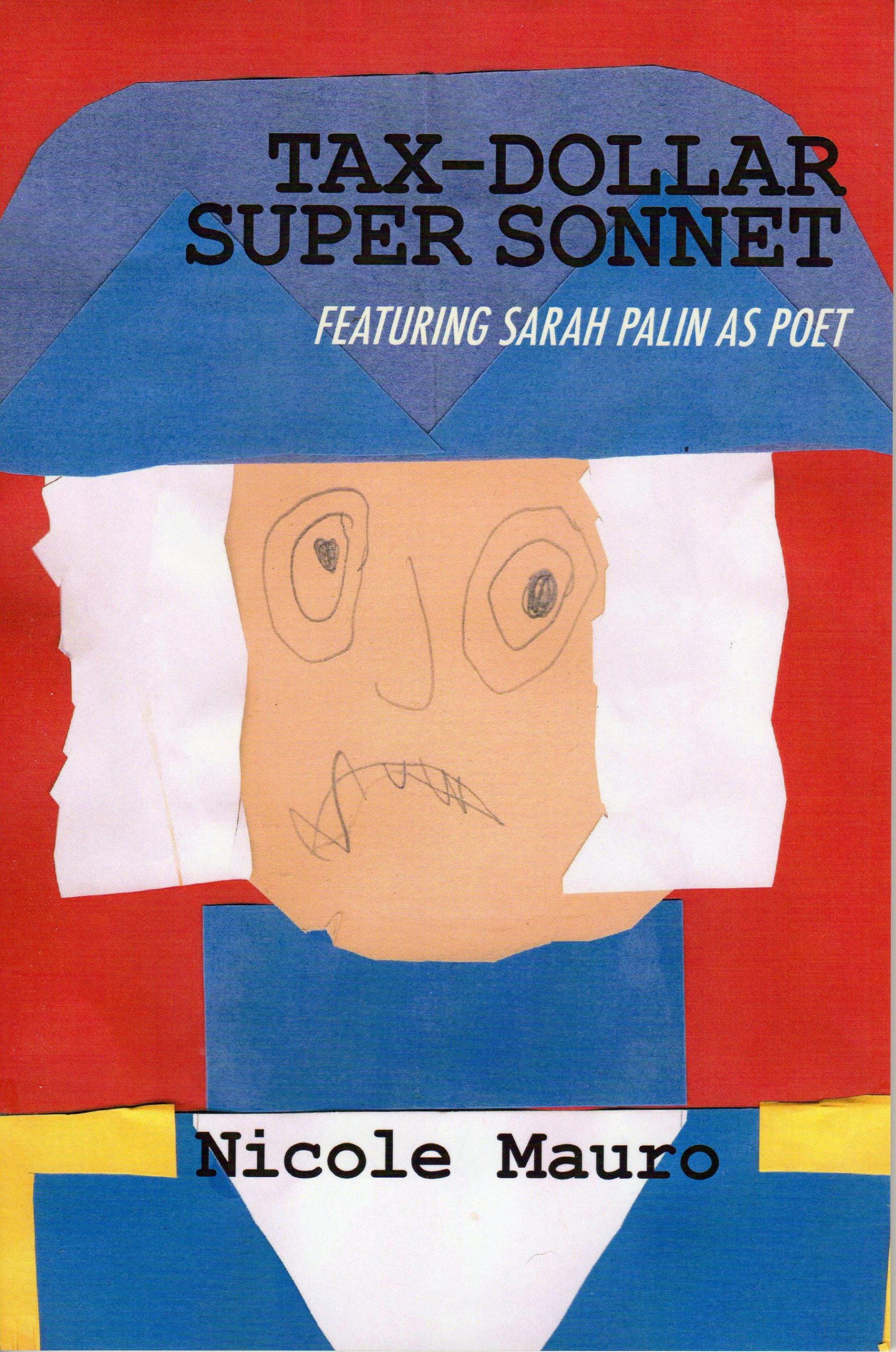

Tax-Dollar Super Sonnet, Featuring Sarah Palin as Poet

This is a found poetry book . . . of sorts. William Shatner did Palin on the “Tonight Show.” He took Sarah Palin’s farewell speech and delivered verbatim in a beatnik style with an accompaniment of bongos and stand-up bass. Hart Seely, Syracuse Post-Standard columnist, seemed to hit gold with Pieces of Intelligence, his collections of poems that he ripped from Donald Rumsfeld. Nicole Mauro takes the idea to the next logical level in Tax-Dollar Super Sonnet, working with the fervor of a mash-up DJ. The borrowed speeches span the history of America and bristle with the newness of the modern age. These poems have a real political edge added back to them, the words reorganizing themselves to fortify new points. This is a found poetry book . . . of sorts. William Shatner did Palin on the “Tonight Show.” He took Sarah Palin’s farewell speech and delivered verbatim in a beatnik style with an accompaniment of bongos and stand-up bass. Hart Seely, Syracuse Post-Standard columnist, seemed to hit gold with Pieces of Intelligence, his collections of poems that he ripped from Donald Rumsfeld. Nicole Mauro takes the idea to the next logical level in Tax-Dollar Super Sonnet, working with the fervor of a mash-up DJ. The borrowed speeches span the history of America and bristle with the newness of the modern age. These poems have a real political edge added back to them, the words reorganizing themselves to fortify new points. A premier line from the latter section “Tea Party Poems” is “I am the new Emily Dickinson with a gun.” This shows the way in which our political leaders have become inflated to tweets or reduced to poetry. The rearranging of these words could give way to unnecessary revolt. A revolt that smells of every revolt. But Mauro takes a po-mo path many times that allows for multiple interpretations and still rings of message.

“Yes we can”

“Yes we can”

“Yes we can”

“Yes we can”

The book starts off with a recent slogan of renown. “44. Chicago—” uses the slogan enough times that it begins to lose its meaning. This alone would be enough in illustrating what the news feed looks like. It recreates modern life in its iterations. This ‘yes we can’ attitude which helped to move and ignite another branch of the civil rights movement seemed to reduce itself to a trite video clip by the end. But Mauro returns to the slogan its very own wonder and dignity:

“It is true” “I” “can”

“make” “them” “all” “hold” “their” “own” “hands”

“Delaware” “Main Street” “Birm-”

“-istan”

The punctuation stands out through the whole work. It allows the reader to see which pieces were intact the ways the original speaker intended. Many of the words are worked in total isolation from the sentences they were born. It becomes a testament to the work that it begins to resemble something like the original, in a warped way. I can make them all hold their own hands. That line says so many things. Is it the independence and autonomy of the modern age? Is it a message of equality, stating that no longer will greater forces be needed? But the enjambment is fantastic. The force behind the mental rhyme of Birmingham and Birm-istan illustrates the way social issues never really leave, but transfer and mutate, the same way these poems do.

As Tax Dollar Super Sonnet continues forward, it digs through history. Each piece could be investigated to see the relevance of the words that Mauro uses for her poems. There is an overall effect at work through the entire book, that of a mash-up artist at an electro festival. Mauro reworks everything the reader could possibly know about inaugural addresses and presidential speeches. She invents rhythms that were suggested by the very men in the position. The reader can’t help but forge imaginings about what the original speech could mean and the intent of the reworking.

“7. Washington—” uses words from President Andrew Jackson’s Farewell Address in 1837. Jackson was such a likeable and approachable president he was once punched in the face by an angry seaman. This sort of accessibility is unheard of in the modern age. This particular poem by Mauro doesn’t speak to this fact but uses rhyme to address the needs of the people—money:

“currency”

“this system of paper” “is a system”

“of” “mischiefs and dangers”

“a” “labor”

The poem acknowledges Jackson as being a man of the people by taking his words and making them rise against the system. It has attention to minor detail while being large and vast.

The overall tone of the book is universal. That it is moving towards new questions. It provides answers to history by proposing new systems. New Order. Re-Working. This says the most. Mauro’s method of dealing with history, in the tradition of the Counter Culture, the means of Burroughs and Ginsberg, is infused with the modern age and Twitter. She is letting the speech of those steering the ship do what it has always done: get tangled up in nonsense and point in more directions than the compass knows exists.