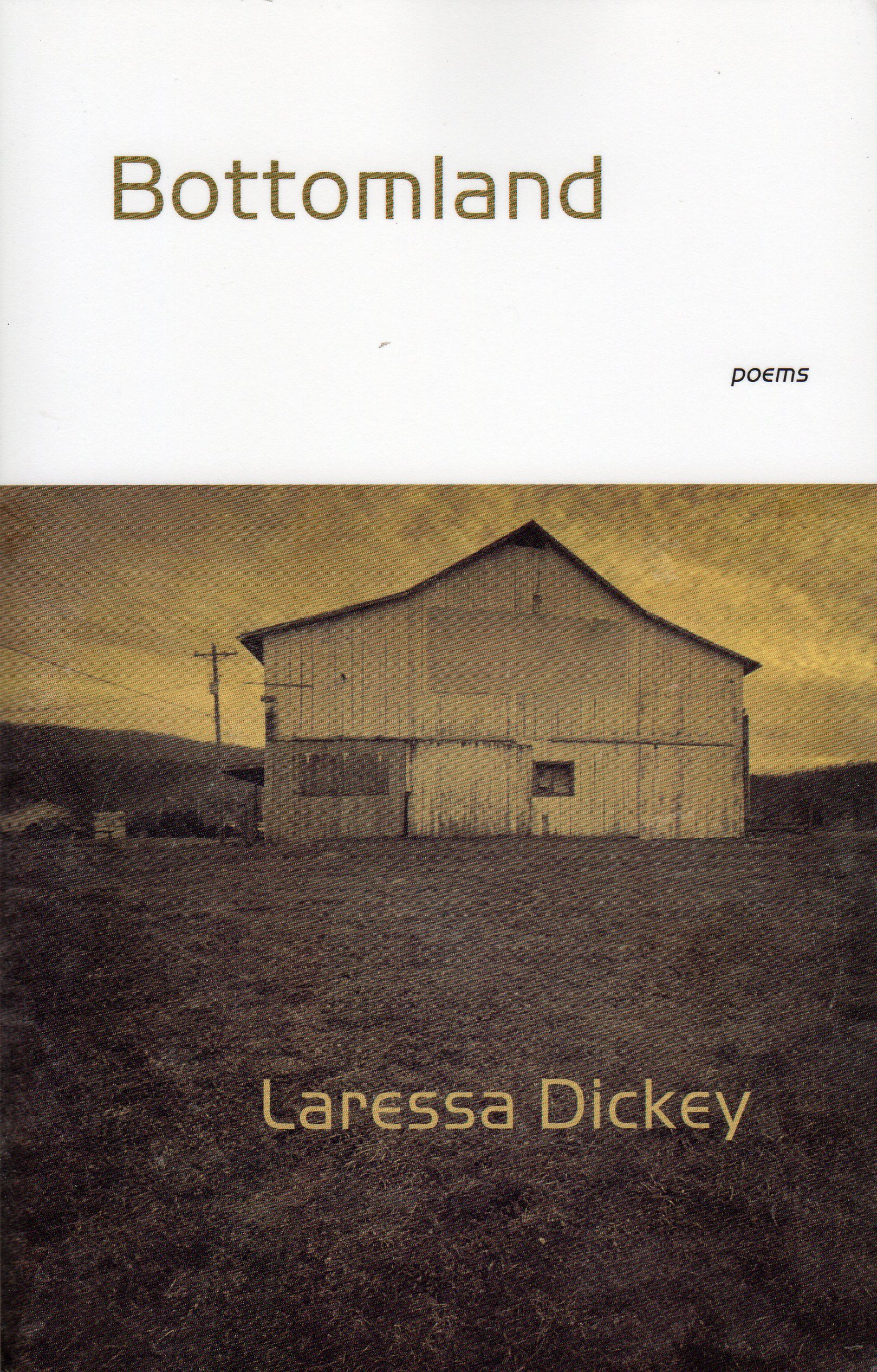

Bottomland

Laressa Dickey’s first full-length collection, Bottomland, portrays a familiar American landscape with a deeply private undercurrent. Pastoral images and their inhabitants play a central role in the journey, but they keep their secrets.

The first section begins with a dark barn and a distinctly rural “dry leaf crackle” among the stripped “tinny tobacco leaves,” with an unexpected reference to Paris in the fourth line: “Now, everything in Paris tastes salty.” A rare proper noun, this is the only time Paris is mentioned in the book. It juxtaposes a familiar outside world with Dickey’s Bottomland, where the only landmarks are Rick’s BBQ joint and the names of family members. The rest is a cascade of images and fragments held together by a thin thread of association, which leads the reader to understand that along with not being a glitzy tourist destination like Paris, this bottomland is not easily found. Nor does it seem to want to be found.

Now, everything in Paris tastes salty. The still rain.

There’s the dry leaf crackle, there’s diligence.

What is better than the willow branch bending?

You sort yourself out, what doesn’t come from cotton.

Tomahawk hatchet, croissant. On the bobbing river or in the row.

There are no timestamps in Bottomland—no mile markers or guideposts. The speaker tells us, “Some stories are shapes burned / together,” and the result is a fusion of time and place. Dickey’s images smolder with unknowns and “ripped strips of memory” where poems jump between decades or generations with subtle references that make it clear details are less important than lyric quality and voice. Characters make cameo appearances throughout the six sections, but no single voice comes close to rising above the rest:

In the photograph, his grandmother sat on the moon. She

resembled dotted daises, ticked by blushing. Not a moment too

soon the red haw. Condense. The family crossed for sixty-eight

dollars a person, onerous now, her garland nose.

And later:

. . . My brother makes pecan pies and wears a blue hat. In the corner, our

mother murmurs the prayer of the 7th horse and rolls a penny along the

slanting floor. No one comes to talk with me. . . . Our mother stomps

mushrooms with her open hands and they puff out smoke.

Dickey’s prose poems vibrate with references to a place that exists more in feeling than in substance. The story that emerges is one of a former home observed from a distance without the expected nostalgia or remorse of leaving. The speaker observes, but doesn’t romanticize the distance, leaving the reader with enough space—often too much—to bring their own variations of home and distance to the work.

What grows toward home? The season

for passage. Timeshuffling

a stiff deck. Who kept score I’m

not recalling.

To walk into the bottomland is to discard notions of understanding exactly who and what have passed through it, and to feel their presence touching every angle of the landscape. I found the poetry bewildering until I let go of the notion that I could follow the story of a place and its people. They are preserved in an intimate texture of space and language, defying any narrative that would seek to pin them down. The Bottomland is not solid ground. It leaves space between things unsaid and takes patience to walk through alone.