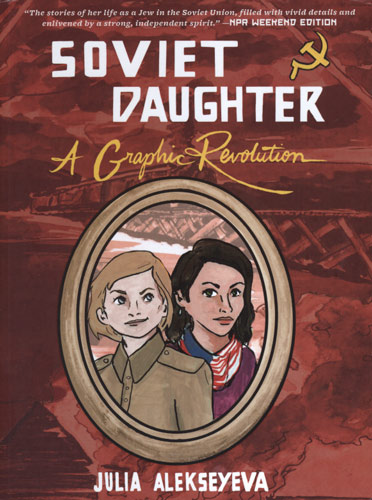

Soviet Daughter

On August 11, Lola met Kyril, the self-professed love of her life. He proposed on the 15th, moved in on the 17th, and they married. This could be a modern love story, except it took place in the late 1930s in Eastern Europe when Joseph Stalin and Adolph Hitler were tossing lives into disarray. The story of Lola and Kyril is just one episode in Julia Alekseyeva’s richly-illustrated memoir Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolution.

On August 11, Lola met Kyril, the self-professed love of her life. He proposed on the 15th, moved in on the 17th, and they married. This could be a modern love story, except it took place in the late 1930s in Eastern Europe when Joseph Stalin and Adolph Hitler were tossing lives into disarray. The story of Lola and Kyril is just one episode in Julia Alekseyeva’s richly-illustrated memoir Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolution.

In an interview, Alekseyeva reveals that when she was four years old, her great-grandmother Lola, her grandparents, and her mother emigrated with her from Kiev to Chicago in the aftermath of the 1986 explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine. Julia knew no English, “kids on my block would tease me and purposefully only speak English . . . even if they were Russian themselves.” In Chicago, her mother took a bookkeeping job, and the grandparents were busy adjusting to life in America, so Lola became Julia’s caretaker and refuge.

When Lola died in 2010 shortly after her 100th birthday, Julia was 21. They were “two generations, separated by 80 years—but somehow united,” writes Julia. Among Lola’s possessions was a private memoir she’d written, and which subsequently became the basis for Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolution. “What lay inside was astonishing. I was so moved that I decided to write about my own life, and about my relationship with Lola—the bravest woman I had ever known.”

Julia, who teaches at Brooklyn College, deftly illustrates chapters about Lola followed by interludes from her own life. For example, Lola revealed details that happened before she met Kyril. Her first marriage to Mitia was one of convenience for both parties. Their marriage license cost three rubles, the equivalent of $1.50, and their divorce cost the same. They had a daughter who survived several health problems including a tumor and scarlet fever.

Julia’s interlude that follows takes us to 2009 when she was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, “a result of radiation poisoning from Chernobyl when I was a kid.” At the time, Julia was a senior in college and underwent radiation therapy. These short interludes tie the two time periods together, a bridge gapping the generations.

Other aspects of Lola’s early life and personality, previously unknown to Julia, emerged. Her early years were beset with periods of fear, famine and tragedy. But also, good times: how she enjoyed parties, her love of dancing, and, at one point, starring in operettas. In 1939, while married to Kyril, they had a son. As described by Lola:

The next year was full of joy. The winter passed by peacefully, and the first days of summer were warm and beautiful. But meanwhile, Hitler’s armies were ravaging Europe, and the Nazis were quietly preparing Operation Barbarossa—the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union.

As the dual story progresses, transitions between the two women’s lives sometimes merge softly, but often Lola’s stories become cliffhangers. Jews in the Soviet Union, Lola among them, faced violent antisemitism. In her own words: “In 1937, the purges started. [ . . . ] Stalin’s henchmen were merciless. [ . . . ] Every day people would ‘disappear.’”

When World War II began in the Eastern Front, Lola was in Kazakhstan, where she was able to work as a typist by day and a hospital volunteer by night. “Meanwhile,” she wrote, “in the Ukraine . . . Babi Yar, September 29-30, 1941, outside of Kiev: the deadliest 2-day massacre of the Holocaust.” Julia emphasizes this horror with a bold two-page drawing of a mass execution.

Then in an interlude, Julia tells that her own relation to the war was “was perhaps more visceral than it was for the average American. For one, I was terrified of Germany and Germans, something that didn’t really dissipate until grad school.” She was also haunted by images of World War II as portrayed in Hollywood films.

She adds that since her great-grandmother died:

I think my personality has unconsciously shifted to become more like hers. Feeling the effects of the recession after graduating from college in 2010 has made me more actively political. I’ve even become much more idealistic, and perhaps a bit optimistic.

“After all,” she writes “governments might change, the historical period might shift, generations might differ. But nothing, not all the guns and pepper spray and police batons in the world, not even time can kill a true idea.”

If you’ve never been drawn to graphic novels, don’t wait any longer to pick up a copy of Julia Alekseyeva’s Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolution for an insider’s observation of history. And if you’re already a fan of the genre, please add it to your library.