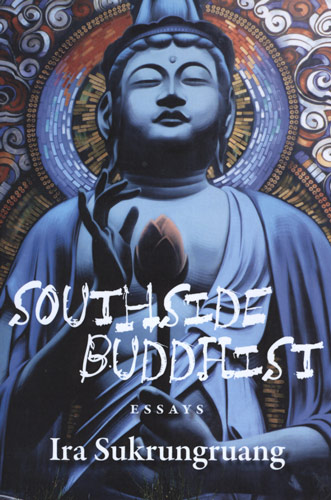

Southside Buddhist

Ira Sukrungruang takes readers through the gamut in this collection of essays, Southside Buddhist. Gamut of what? You name it: emotions, literary styles of nonfiction, life experiences, ages, cultures—all in this one remarkable collection of essays. Ira Sukrungruang takes readers through the gamut in this collection of essays, Southside Buddhist. Gamut of what? You name it: emotions, literary styles of nonfiction, life experiences, ages, cultures—all in this one remarkable collection of essays.

The collection begins with “Abridged Immigrant Narrative,” a kind of family mythology. In subtitled sections, Sukrungraung recounts the story of his father’s and mother’s lives in Thailand before coming to the United States, their meeting, marrying, having their son, Ira, and divorcing. The section titles each include “Immigrant” followed by: on the Run, Love, Joy, Marriage, Dreams, Son, Pride, Protection, Dreams II, Lessons, Borders, Loyalty, Dreams III, Fear, Fear II, Fear III, Regret, and ending on The Immigrant Son . . . . The progression is clear to see, like so many lives—such hope and love and joy to begin, then the complexities, complications, and struggles.

Readers of his first memoir Talk Thai: The Adventures of a Buddhist Boy will be familiar with some of this story already. Talk Thai was told from the adult going back and reliving that childhood perspective, with the adult commentary included, but still retaining focus on the point of view from the child. In Southside Buddhist, Sukrungraung goes back and provides more of an adult point of view on the lives of his parents, showing a more compassionate portrayal of their struggles and the choices they made.

It would be too easy to say this writing is Sukrungraung searching for identity. This collection of works feels different. From his immigrant parents’ home and the eclectic streets of Chicago as the backdrop, to his trying to find where he fits in: his move from the city to the country with his friend whom he ends up marrying, his move from “up north” to Florida, and a few visits to Thailand in between. This work is more about place and space. The place and space within us. The place and space around us. The place and space we feel we occupy, either comfortably or not. And ultimately, our attitudes and perceptions about all of these.

In “Tots-R-Us,” Sukrungruang tells of preschool days. The ride with his parents to daycare and back connects a young Ira with family and Thailand, “Good days: Laughter and talk of Thailand. Bad days: Quiet and FM 100 elevator music.” At Tots-R-Us, Ira is quickly “married” (preschool style) to Dawn, who quickly binds him to a pretend family he supports by going off to work. The perfect happy family, which was not the same kind of perfect and happy Ira knew outside of preschool:

Our happiness existed inside that car traveling along Chicago streets, making its way to daycare. Bad days or not, there was safety in the Volkswagen Beetle, and safety was the closest thing to happiness for my immigrant parents. Outside the car was the unknown. Dangers lurked in the guise of language and culture. My parents were out of sync with the rhythms of this land, a city where skyscrapers jutted from concrete foundations.

The challenge in reading these essays was in getting to know Ira so much more. I already adored this little Thai boy who struggled with his growing up in Chicago. I liked that he had a tough side to him, his Southsider Chicago bad boy. But Southside Buddhist introduces more of a mean side that little boy either grew into, or that this collection allows the more appropriate venue for Sukrungruang to share. Knowing some of the stories here may not have endeared me to that little boy in Talk Thai, but couched in this collection, I can understand their place. For example, in “The Cruelty We Delivered: An Apology,” Sukrungruang remembers his and his friends’ (bullying) actions toward a neighbor mate who much later in life commits suicide. I wouldn’t have been endeared to his cruel behavior written in the child’s memoir, but now as he looks back and feels the guilty pain of “boys just being boys,” I empathize with Ira.

Southside Buddhist goes to the next phases of Sukrungruang’s life: to his falling in love, which is sweet, but also to his growing dark side, his struggles with depression and continuous dysfunctional relationship with food and body image issues. I have to admit, at one point, I was so upset by what was happening to Ira, I wanted to stop reading the book.

For five, six, seven years, I suffered. (Latin, suffere, to bear.) This amount of time seems short, considering the longevity of our lives. (See what I did there? I tried to play it off. Tried to lessen what happened to me.) But when you have a two-ton elephant on your chest, time no longer registers in the same way. In fact, you lose all sense of linearity. For me, seconds moved backwards, moved years, moved months. I could not, as a Buddhist, live in the now. What was now, anyway, but a hokey way of being? What was the now without the then? You see, time, for me, was like this paragraph: it started and it went in every which direction. I was living (a debatable word here) in so many disparate time zones, or better yet, because I was living entirely inside my head, time was relevant, and when time was irrelevant, who needed to be on time?

A famous psychiatrist line: “When did you start feeling this way?”

There is no start. Depression doesn’t employ the once upon a time story structure. It does not move in chronological order because depression is the antithesis of order. It is suddenly there. Or perhaps, it has always been there.

I did keep reading and found Sukrungruang’s writing to be some of the most open and honest about what he was suffering through, without the sentimentality, almost matter-of-fact and observational of his own state of mind, his own state of being: “And here’s the scariest part, and because I want to be frank about this, I will come out and say an even scarier word than depression: Suicide. I wanted to commit suicide. (Neo-Latin suicidium, of one self.)”

“Body Replies” continues Ira’s search within himself to create a safe and comfortable space. Those who struggle with body issues will understand perfectly the conversations Ira has with himself, the lies he tells others. Like when his yoga instructor asks during a conscious walking exercises, “What are you thinking?” and Ira replies “I’m thinking heel then toe,” but writes, “I don’t tell him the truth. I don’t tell him how much I hate myself, how much I hate Body. I don’t tell him how much I hate that I can’t walk correctly.”

These work as stand-alone essays, but their true value comes when they are layered on these pages, one after the other, one interweaving the story of another that came before. I felt by the end that I had ‘gone through it’ with Ira—his childhood, his moving from place to place, his depression, his continuing into a calmer less restless adulthood, his acceptance of change. The final essay, “Southside Buddhist,” provides the perfect wrap up for the book, cycling back to the beginning family myth. This is now Ira examining who he has become because of who he was. There is no searching here, and I wouldn’t say there’s any great revelation of finding self. There’s an acceptance of continuum. An acknowledging of how space and place have shaped this young man, and how space and place can be identity, whether it’s where we are now or not:

The Southside me is like the Southside neighborhoods with the cracked and weedy sidewalks, the eroding brown brick buildings, the abandoned factories. The Southside resists any type of change, unless it’s for the worse. . . But amid the deterioration, there exists loyalty. It’s like a tiny flower sprouting in a mound of shit.

Sukrungruang is a nonfiction writer worthy of close examination for his varying styles within the genre, for his ability to write to the grit of prose as well as the lilt of poetry, all within the same piece. His work has been labeled “nature writing” in the same breath as “immigrant narrative,” but what resounds is his steadfast focus on the syntax, the rhythm, and the narrative pacing. His craft is clean. His place is with us, on the page.