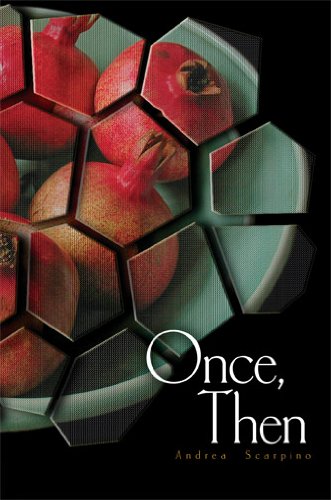

Once, Then

Once, Then by Andrea Scarpino is a collection of elegies that are caught in the tension of two worlds, the scientific and the spiritual. In attempting to understand the aftermath of loss, Scarpino turns to form, and her lyrical, shortly-woven lines sing. The collection often features the profiles of people, those closest to Scarpino, and also mythic figures such as Persephone and Achilles. What results is a poet deeply engaged with the world. Once, Then by Andrea Scarpino is a collection of elegies that are caught in the tension of two worlds, the scientific and the spiritual. In attempting to understand the aftermath of loss, Scarpino turns to form, and her lyrical, shortly-woven lines sing. The collection often features the profiles of people, those closest to Scarpino, and also mythic figures such as Persephone and Achilles. What results is a poet deeply engaged with the world.

One technique present throughout these poems is the use of juxtaposition and irony. In the first few poems, we learn that Scarpino’s father is a microbiologist and believes in the physical world. In “My Father and the Nuns, 1956,” she describes when her father had to teach nuns how to “pipette, swab Petri dishes / with cotton sticks, wipe down counter tops // with iodine.” The irony is immediately present. The nuns are required, in their “black habits” to meet a state standard for science education. In this poem, science meets religion. We might expect resistance and tension, but what happens is a remarkably poetic fusion of two worlds. They examine DNA through a microscope: “signs of God like strings / of beads through chalky hands.” The DNA serves as the proof of a God as the nuns pass rosary beads through their hands.

Scarpino returns to this juxtaposition often. In a later poem she describes her father in a hospital bed believing he hears his name as his body rises. In a role-reversal, Scarpino must be the scientist and assures her father of the factual, scientific world: “I played the scientist, blamed your medication, / seizures, hearing aids. What else could I believe?” This is when the confidence begins to unravel. The doubt in a world so perfectly scientific is tangible on the page. Scarpino writes, “Truth like beveled glass: for weeks before you died, / your name was called, your body pulled away.”

It is these father/daughter poems that reveal tender language and intimate images. In the poem, “Self Portrait as Achilles,” the father kneels before his young daughter and presses on her feet, caring for her ankles when it seemed myth, not science, was the only way to cure her. Other “Self Portraits” appear in the collection, one as a pomegranate, another as a stone.

These poems are intensely observational and perceptive. In “Too Much of Anything” Scarpino compares ballet to physics in an extended metaphor to describe losing a girl she loved to a car accident. The couplets create a force that pulls the energy down the poem, in the same way that “gravity” “bent me to my knees. / What it means to be bound, free.” Exact and beautiful, this poem strikes a personal chord, and is one of the best in the collection.

Whether describing the death of a childhood apple tree or paying tribute to the lost lives of Hiroshima, Scarpino arrives at an understanding of the world that is complicated, contradictory, and ultimately dependent on the human experience. Full of loss and mourning, Scarpino ends on something more certain. She writes, “The earth / in unfolding light, grace.” It seems she’s found something spiritual and scientific. The result? Poetry.