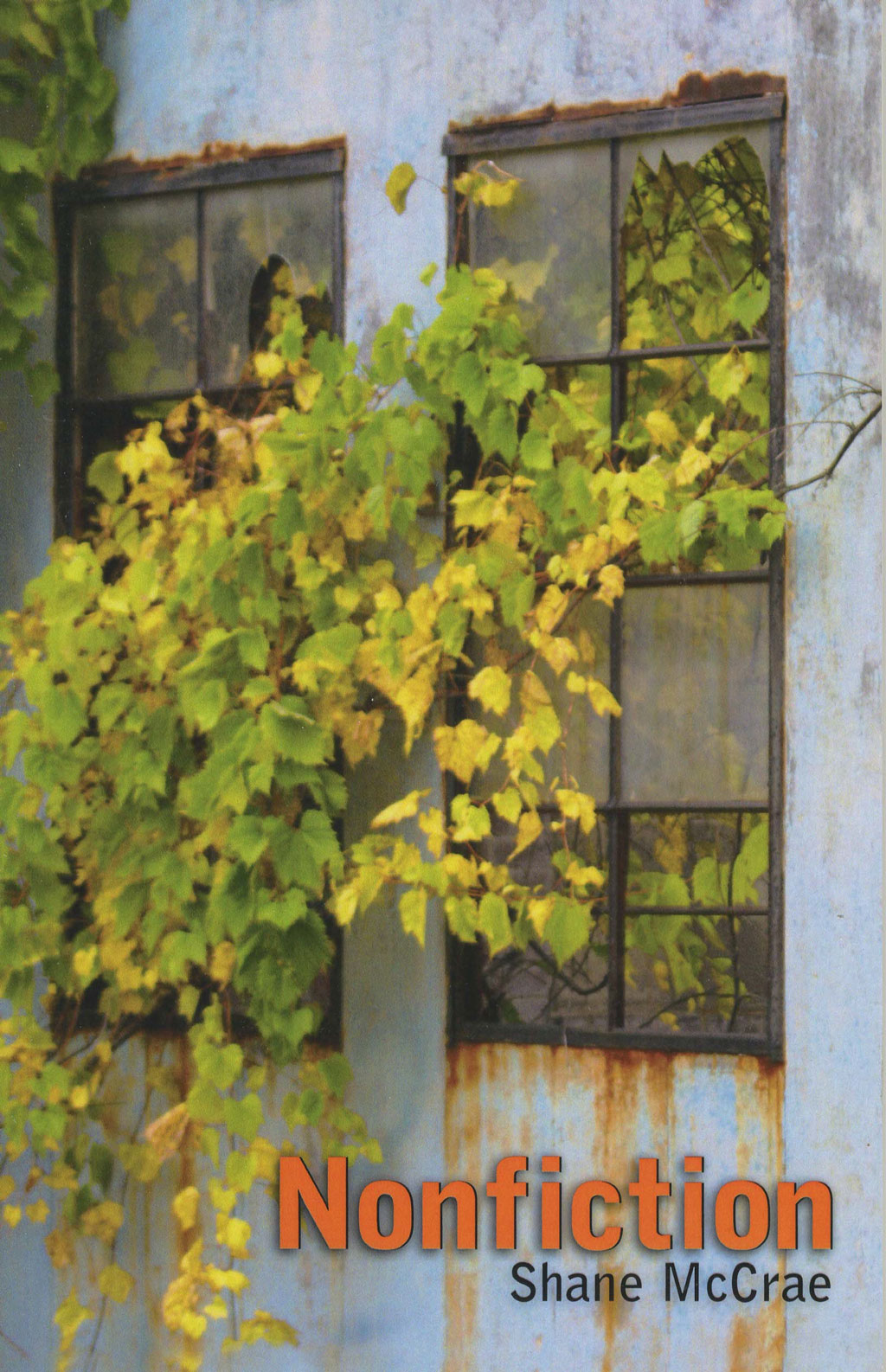

Nonfiction

Shane McCrae in Nonfiction, a collection of poems, urgently requires readers to face both the visible and invisible truths of our American culture and society, present and past. Throughout these poems, the lyric voice of our culture and its various speakers emit a language that insistently stammers and stutters, resulting in poems that stun readers with pure lyrical beauty. The rhythm of the line, the stutter and repetition, so closely mimics the messy, rarely perfect, inner dialogues of the soul. Shane McCrae in Nonfiction, a collection of poems, urgently requires readers to face both the visible and invisible truths of our American culture and society, present and past. Throughout these poems, the lyric voice of our culture and its various speakers emit a language that insistently stammers and stutters, resulting in poems that stun readers with pure lyrical beauty. The rhythm of the line, the stutter and repetition, so closely mimics the messy, rarely perfect, inner dialogues of the soul. Through this language, McCrae forces readers to witness the harrowing truths of our culture, truths that are visible: the color of our skin, race, but so little of the actual self, and truths that are invisible: prejudice, pain, power, and the soul.

In a short collection, just twenty-five pages long, McCrae expertly weaves and links narratives between poems that deepen our awareness of the truth. The collection begins and ends with the same title: “An Incident in the Life of Solomon Northrup a Free Man,” but the two poems show different angles of truth. These poems, following the narrative of Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northrup, an account of a free man’s path back to slavery, expose the elusiveness of memory and the way in which the past is easily forgotten. In the opening poem, McCrae first introduces us to his lyric stammering:

Spring it was spring was spring in the morning spring

My wife whose skin is summer wheat

had gone

To cook at Sherrill’s Coffee House whose skin is wheat had gone

Over to Sandy Hill

My wife Elizabeth my wife Anne and Elizabeth

Our oldest daughter

It spring in also spring in Sandy Hill

From the first few lines of the poem, we begin to see the speaker reckon with memory, repeat in slight variance “My wife whose skin is summer” and later “Elizabeth whose skin is sun.” The repetition and slight change in the phrase creates a cacophony of voices. What this poem does strikingly well, as do all of McCrae’s poems, is establish the presence of many characters, real and complicated, that attracts a haunting energy to the line. This opening poem urgently and with panic begs an overarching question for the collection: how can one make sense of the victim’s dilemma using standard, calculated syntax? As impossible as it is to understand the capacity of slavery, it is equally impossible to express its current impact on society. The slave as victim to society has been replaced by new positions: the child of a sex abuser, the prisoner, victims of racism.

While the victims of slavery make up a large part of the lyric voice of Nonfiction, so too does the victim of sexual abuse. In the poem “Visible Boy,” the young boy feels that in some way the black color of his skin is to blame for the abuse. This is the visible tragedy of the poem. Invisible, though, is the inner feeling of shame and shattered fragments of victimhood. The boy in this poem thinks he should be a woman, and attempting to do so, to feel beautiful as to not deserve such abuse, he sets out to spread himself on rocks like the beautiful women he sees in magazines. This is to his own demise, though, when he’s swarmed with fire ants. McCrae has portrayed the life of this boy with such courage and as readers we must feel deeply distraught and moved to action. This is just one of the “truths” that is almost too hard to bear.

At the core of these poems is a desire to give voice and awareness to the victims of our society. This desire, at times so profound, can also destroy us. McCrae writes an essay on “How to Survive Desire” about a prisoner’s attempt to survive his jail cell, to put away every desire he once had, to demolish any desire for decent living. In one section, the speaker, confident and with a voice of past knowledge, tells a prisoner about sealing off his cell, which of course we know to be impossible. This satiric advice links to a previous poem in which an entire building of slaves was burnt to the ground—evil, injustice, deeply rooted hate, are impossible to escape from, but McCrae suggests: “Understand you are powerless to fight it / Fight it.”

A tragic lack of hope concludes the book and readers are left to consider if they have been “blind” to the truths of our society. The blindness is both literal and figurative. We choose to be blind to that which we do not want to see. And this is often a cultural blindness: we turn our faces away from child sex abuse, away from the deeply rooted issues of race that are still heavily present in our prisons and societies. The last lines of the book pose an irony, though, one in which the speaker’s eyes are open, but open to darkness: “. . . but I couldn’t understand I felt my way around / Crawling and in the darkness / I after a while couldn’t be sure / My eyes were open.” McCrae asks us to see more, to hear more, to feel more. This lyric stammering, unique to McCrae, is deeply powerful and intensely felt.