Chtenia – Summer 2015

The year was 1964 and Leonid Brezhnev had just taken control of the Soviet Union. Nikita Khrushchev had recently been expelled as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as well as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, thoroughly ending another era of autocracy in Soviet Russia and ushering in a collective leadership. Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin took the stage to powerhouse Russian politics, and henceforth brought about the Era of Stagnation in the USSR, creating hardship and creative inspiration for citizens of the massive state. The year was 1964 and Leonid Brezhnev had just taken control of the Soviet Union. Nikita Khrushchev had recently been expelled as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as well as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, thoroughly ending another era of autocracy in Soviet Russia and ushering in a collective leadership. Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin took the stage to powerhouse Russian politics, and henceforth brought about the Era of Stagnation in the USSR, creating hardship and creative inspiration for citizens of the massive state.

This comes eleven years after the death of Joseph Stalin, nineteen years after the end of World War Two—both sources of turmoil for the Russian people reflected in the poetry and art created during this period. After World War II ended, 1.5 million non-Russians had been displaced in an effort to “Russify” them and mark them as part of the Soviet Union. Stalin didn’t stop there—he built communist governments in Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia by the end of 1948, creating buffer states to further isolate and protect the Motherland from Western influence. Millions of people had their lives changed forever.

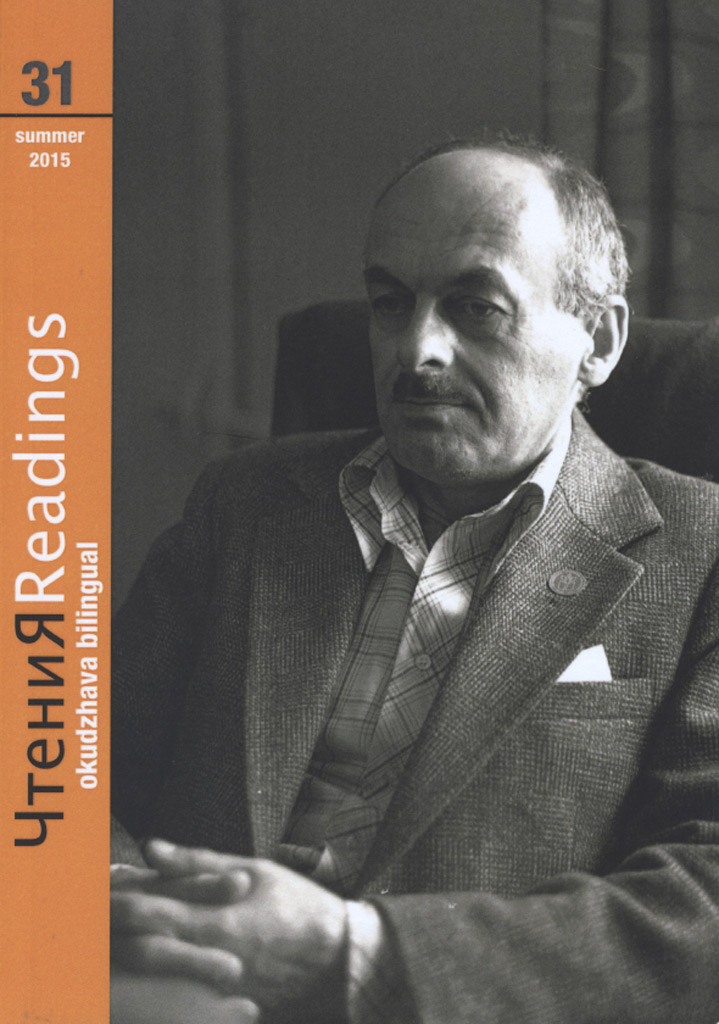

All of these topics—Stalin’s rule, World War II, and the economic and political stagnation of the Brezhnev era—are relevant when studying the life and work of Bulat Okudzhava, Chtenia’s spotlight Russian poet and songwriter for the magazine’s 31st issue. Born in Moscow, two years after Stalin took office, to a Georgian father and Armenian mother, Okudzhava would come to shape Russia’s capital city into the birthplace of the Russian bard.

The start of his career was simple and quiet: he began performing his poetry with a guitar accompaniment in the homes of his friends. His work quickly gained traction, and it wasn’t long after when he was booked for public concerts while homemade tapes circulated through the streets of Moscow. And so began a sub-era in Russian history—the era of the rising Russian bard.

Very few can compete with eloquence and musical style found in Bulat Okudzhava’s work. Symbolism, extended metaphors, a bridge between ordinary life and the unordinary, and irony imbue Okudzhava’s songs, distinguishing him from other bards of the time period. In a poem reflecting on his time spent at war, after he enlisted in the Red Army at the age of seventeen, he brings a sense of childlike disbelief at having been a part of warfare. He writes:

You know, I somehow can’t believe I really went to war.

Perhaps I saw a picture once, the kind that schoolboys draw,

in which I stamped and waved my arms and raised an awful din

and felt quite sure I would survive and hoped that we would win.

Another poem calls upon a foot soldier to question his place in the war and at the same time acknowledges the strange pull combat seems to have on men, the sentiments seemingly at odds with one another, yet neither giving in to change:

One lesson we’ve learned here, that nothing on Earth but the marching is real.

Admit it, comrade soldier, for men such a life on the march has appeal.

One foot, then the other. Yet we’re kept awake nights by one troubling thing:

Where is it we’re headed, when marching from places just bursting with Spring?

Okudzhava’s work is especially rich in themes. Although war seems to be a prominent topic he reflected on in song, Okudzhava was also inspired by the happenings of everyday life. In addition to songs and poetry, he wrote a number of stories, most resonating of which is titled “The Private Life of Alexander Pushkin.” The narrative, an autobiography of Okudzhava’s own life, recounts when he, as a recent graduate of university, finds himself sent as the first college graduate to teach in a remote village east of Moscow. The narrative reveals himself as young and arrogant, prideful of the university badge on his jacket, before the experience humbles him. The issue contains numerous other narratives about Okudzhava’s life, each resonating in its own way.

The Chtenia issue on Okudzhava offers a near complete experience of his work, stopping just shy of sitting us down in a candle-lit lounge to witness his performances first-hand. But the pieces showcased in this issue bring him to life so we can imagine just that. Those involved in the publishing of Chtenia certainly make an impressive tribute to one of the most important Russian bards of all time.

[www.russianlife.com/chtenia]