Valley Voices – Spring 2015

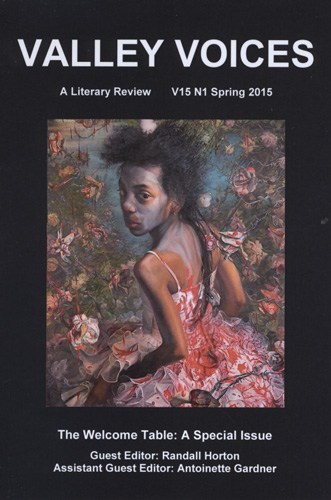

There are voices that are almost always overshadowed despite that their histories are embedded in our nation’s roots. Centered on the glossy cover of Valley Voices is Margaret Bowland’s painting of a young, black girl—her brown skin thinly painted white. Her attire consists of a white dress, blood spattered against a garden of white roses and cotton blooms. Ahead of her, beyond the splashes of red, a turquoise blue land, perhaps a more promising place. With her face turned almost completely towards me, and hopeful, she leads me there into that place to listen to the voices that I so rarely get to hear. There are voices that are almost always overshadowed despite that their histories are embedded in our nation’s roots. Centered on the glossy cover of Valley Voices is Margaret Bowland’s painting of a young, black girl—her brown skin thinly painted white. Her attire consists of a white dress, blood spattered against a garden of white roses and cotton blooms. Ahead of her, beyond the splashes of red, a turquoise blue land, perhaps a more promising place. With her face turned almost completely towards me, and hopeful, she leads me there into that place to listen to the voices that I so rarely get to hear.

Guest-editor Randall Horton dubs this issue “The Welcome Table,” after Leola Dublin Macmillan’s critical essay, which examines the self/woman in the context of the black community. In it, she argues: regardless of age and experience, black women “[ . . . ] are denied access to the protected space of ‘grown folks,’ despite the adult realities of their lives.” Although a woman may be a mother with a career, a spouse and a home, she will often times be exempted from the discourse of her elders. Although my skin color and heritage is a different hue, my sister and I have experienced this voicelessness at home. In a Mexican household, we are not invited into our parents’ world. We, like so many women of color in their communities, are the others.

Sandwiched between essays are poems and the occasional sprinkle of fiction. April Gibson’s poem “Etiquette,” and Becky Thompson’s “Travel Restrictions,” continue to cultivate Macmillan’s black feminist examination. In “Etiquette,” Gibson writes, “[ . . . ] you pretend to care in company / eat packaged food on paper plates when they leave,” emphasizing the façade women typically put on when inviting others into their homes. No one wants to see a broken woman, depressed and restricted by her illness. Similarly, in “Travel Restrictions,” Thompson reminds the reader that all women in the western world do not have a language that nurtures her every aspect; she is constrained by her body:

[ . . . ] the world so much smaller

than it used to be,

as linguistics still

keeps us honest about

where tongues don’t yet go.

Felecia Studstill’s poem “Mother of a Slain Son” speaks to the current issues surrounding police brutality. The narrator begins with irony: “Truth be told, I wanted him to die,” and continues to list the ways she wishes her son would have died. She imagines him dying of boredom, of grief and laughter, and old age. But of all the deaths her son could have had, she never wanted it to be murder. As a spectator to tragedy, I can only feel secondhand grief. This poem, amongst many others written and not yet heard, should be stretched across the nation and embraced by everyone regardless of heritage. After all, art is where action begins.

Joseph Ross knows the power of words and uses them to write, in memoriam, of Trayvon Martin and Israel Hernandez, both killed in Florida, one by neighborhood watch, the other by police. He even goes so far as to see the case behind George Zimmerman’s eyes (Trayvon Martin’s killer) and pens, “Realize he is a teenage boy.” That line echoes in my chest.

Metta Sáma’s piece “The Story of Famine” is a short coming of age narrative written using the stream of consciousness technique. In four pages, Sáma writes about a proud father who feeds his son only the freshest ingredients, and who, “[ . . . ] get[s] a lot of strange looks at the office [ . . . ] but those people their brains are still chain they are still oppressed but you and I we are strong men real men.” While this father fights to keep his son and pride alive, his son silently boycotts the produce entering his body, knowing that thousands are suffering to feed him.

The final narrative, Christopher Dowd’s “The Coriolis Effect,” speaks of generational suffering—inherited deaths. After discovering he will succumb to the same fate as his father, the narrator travels to Ecuador seeking to find the same magic that his father experienced. Instead, he finds that while he may be unable to pick up a pen, he is capable of typing out his sentiments to his daughter, unlike his father who used his nurse to dictate letters. There is something so powerful about direct communication, even when the words reach us after death.

Amid illnesses and violence, as presented by essays, poetry and fiction, are reviews written about collections that contain more unheard voices.

Valley Voices welcomes readers to a reality where they can engage in a discourse unknown to them. As tragedies continue to dominate American media, artists call to attention our ignorance and force us listen to the voices that so often get overshadowed.

[libguides.mvsu.edu/valley-voices]