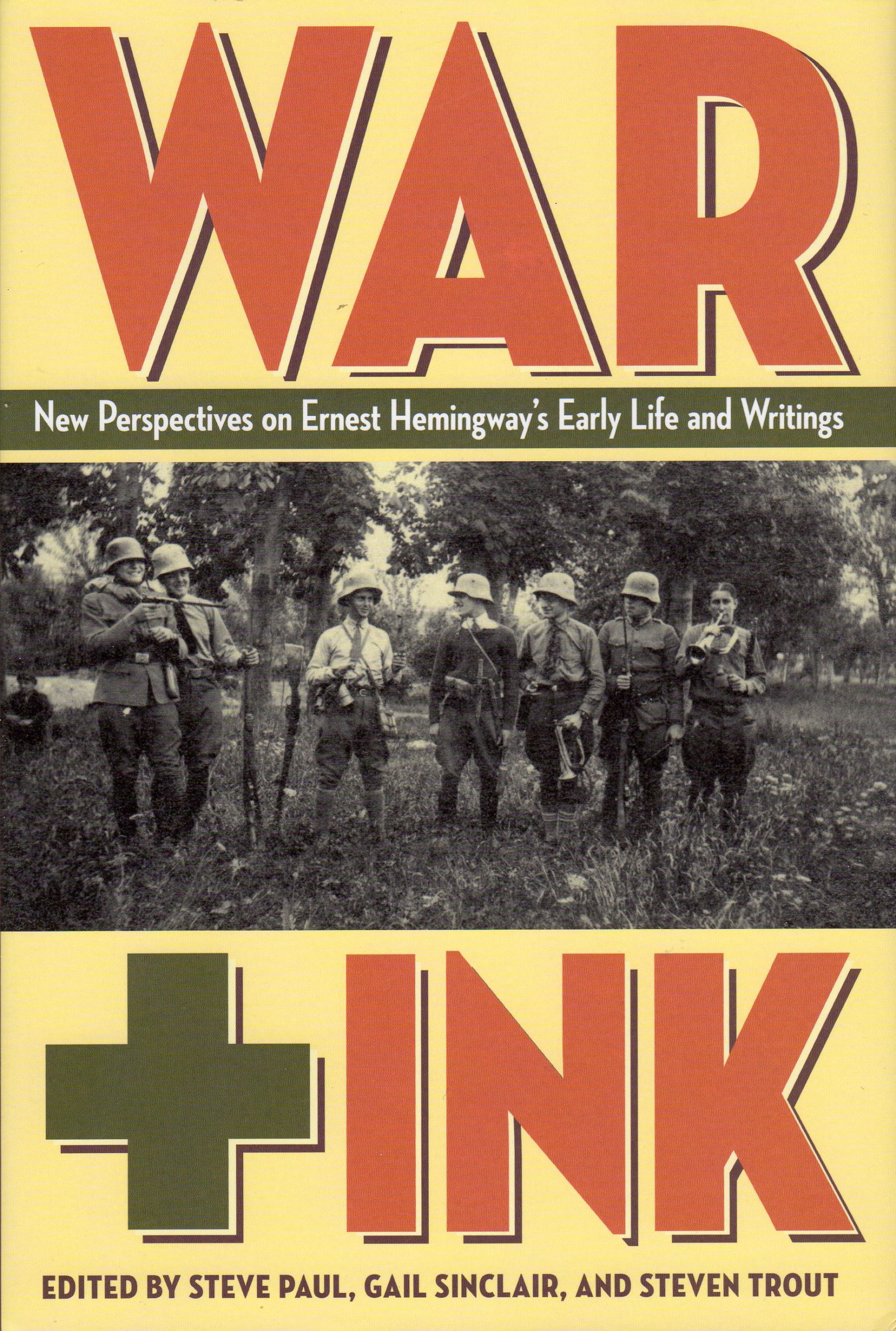

War + Ink

New Perspectives on Ernest Hemingway’s Early Life and Writings

Steve Paul, Gail Sinclair, & Steven Trout

January 2014

Lydia Pyne

Hemingway’s literary world is nothing if not well-studied. Between 1917 -1929, Ernest Hemingway’s early adult years are marked with journalism, war, marriage, expatriation, and his own struggles as a writer attempting to make inroads into the growing scene of European literati. Where most scholarly work has focused on Hemingway’s personal journey in his literary career, the surrounding contexts of his work are less emphasized. In War + Ink: New Perspectives on Ernest Hemingway’s Early Life and Writings, editors Steve Paul, Gail Sinclair, and Steven Trout focus on the social and cultural histories of Hemingway’s early work, highlighting detail from a swarm of Hemingway scholars. War + Ink is a collection of eighteen original essays that span Hemingway’s early career. These essays—from veteran as well as emerging Hemingway experts—focus on Hemingway’s days as a “cub reporter” for the Kansas City Star and his time as a “thrill-seeking Red Cross volunteer and wounded war hero.” Although these large blocks of Hemingway’s biography are well-known, the method and attention to archival detail give the reader a sense of discovery by encountering a “new” detail about Hemingway’s life. Fundamentally, all of the essays focus on the power of Hemingway’s written communication, whether through letters home, stories filed, or snippets of unpublished stories. War + Ink is a careful balancing of supportive detail, literary analysis, and biographical sketch.

All of the eighteen chapters work to strike that balance. Hemingway’s letters home show a playfulness and understatedness in their syntax and diction, as illustrated in Ellen Andrews Knodt’s “‘Pleasant, Isn’t It?’: The Language of Hemingway and His World War I Contemporaries.”

My work is getting more interesting each day. We are in the Army College for Scouts, Observers, and Snipers. Have lots of study of maps, airplane photographs, compass and are just starting on our night training. We are taken out into the woods and after we get what is called our “night eyes” we are separated and have to go forward to a certain position, crawling you know, and make note of all the noises we hear, shadows we see, gun flashes etc. and return by a different route to our starting point . . . because our job will be roaming around “no man’ land” at night…“The whole things is just like a bunch of kids playing Indians . . . I’ll be a regular old Buffalo Bill when I get back.”

There’s a complex simplicity in Hemingway’s writing that Knodt notes is indicative of what readers would eventually come to expect in Hemingway’s “classic” works. The rhythm, pacing, and flow from these archival gems provides literary and biographical context to Hemingway’s later works.

One of the most interesting pieces in War + Ink comes from Matthew Forsythe’s essay, “The Fragmented Origins of Ernest Hemingway’s ‘A Natural History of the Dead.’” Forsythe opens the essay in 1929, when Hemingway returned from his father’s funeral and was attempting to revise A Farewell to Arms—instead of the now-classic piece, Forsythe describes a rather forgotten short story “Death in the Afternoon.” At just under five hundred words, “Death in the Afternoon” is really a short scene sketch—a sketch that quickly works to become an extended metaphor or allegory. A wounded, unconscious solider is taken to a cool cave where dead soldiers were kept in an impromptu morgue; an assistant to an overworked doctor expresses concern that a still-live solider isn’t immediately treated and the doctor brushes off the idea that the solider is still alive. The unconscious solider lives for three days and then dies. “He was alive all the next day. By that time there was a report around that he was Christ.” Forsythe’s interesting play with the piece however, is in the quasi-biography of “Death in the Afternoon” as a meta-archival object. “Death in the Afternoon” is a fragment in the Kennedy Collection; its literary phylogeny is difficult to trace (becoming part of “A Natural History of the Dead”), and it’s a piece Hemingway kept coming back to.

War + Ink: New Perspectives on Ernest Hemingway’s Early Life and Writings, by editors Steve Paul, Gail Sinclair, and Steven Trout shows the fundamentally iterative nature of thematic history and archival sources. The eighteen unique essays that comprise War + Ink illustrate the brilliant scholarship that surrounds Hemingway literary studies. Although academic and technical, War + Ink contextualizes the power of cultural and social history in Hemingway’s early work. For Hemingway aficionados and scholars, War + Ink is truly For Whom the Book Tolls.