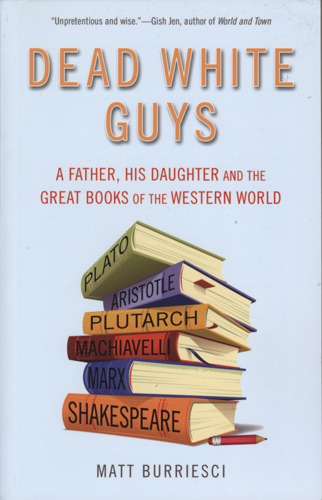

Dead White Guys

A Father, His Daughter, and the Great Books of the Western World

Matt Burriesci

June 2015

Valerie Wieland

If you half-snoozed through the classics at school, reading Matt Burriesci’s Dead White Guys is a shrewd way to refresh your knowledge. The book is subtitled A Father, His Daughter and the Great Books of the Western World. It includes visits to philosophers and storytellers such as Plato and Plutarch, Montaigne and Shakespeare, John Locke, Adam Smith and other notables. Author Matt Burriesci deftly combines their teachings with his own experiences and ideas to equip his daughter with lessons for a good life. If you half-snoozed through the classics at school, reading Matt Burriesci’s Dead White Guys is a shrewd way to refresh your knowledge. The book is subtitled A Father, His Daughter and the Great Books of the Western World. It includes visits to philosophers and storytellers such as Plato and Plutarch, Montaigne and Shakespeare, John Locke, Adam Smith and other notables. Author Matt Burriesci deftly combines their teachings with his own experiences and ideas to equip his daughter with lessons for a good life.

He began writing this book when his daughter Violet was born in 2010. He intends it as a gift for her 18th birthday, though I think it’s wishful thinking on his part to figure she won’t read it until then.

Burriesci addresses Violet throughout and begins most chapters with a few paragraphs about one or another incident in his own life. Sometimes he serves up a lesson he learned or illustrates one of his own failings: “When I was 23 I was a drunken, fat mess. I was living with two heroin addicts—one of whom was a 17-year-old girl—in an apartment I couldn’t afford, in a city I despised, in a job I couldn’t stand anymore.” Years later, in another city, he’s at an Olympic-size swimming pool. “My gut hung over my swimsuit. I dove in the water, and it was freezing, and I began swimming. After four laps, I got out, went to the locker room, and threw up.” Six months later, he’d cleaned up and was writing.

Vignettes like that lead to the crux of the book, which is that studying and analyzing the men he writes about, or even just being aware of their teachings, is of great value.

Burriesci points out that he purposely picked individuals who don’t “share the same point of view,” and emphasizes they weren’t always right:

It would be an understatement to say that Aristotle was hugely significant, but he was also hugely incorrect about a great many things. He is a racist, without doubt, believing the Greeks superior to all other people. This allows him to justify things like slavery without much trouble [ . . . ] And unlike Socrates, who believed that man was quite insignificant in the great scheme of things, Aristotle believed that man—and the planet Earth itself—were literally the center of the universe, a belief that caused 2,000 years of astronomical contortions because people just assumed that Aristotle must be correct. He was not.

In his chapter on Plato, Burriesci talks about democracy vs. a republic. He writes that “Socrates unleashes a brutal critique of democracy in the Republic,” and tells Violet she doesn’t live in a democracy. “You live in a republic. It’s not a semantic distinction. The United States has never been a democracy and it never will be. Ancient Athens was actually a true democracy, in which everyone (well, at least all the propertied men) voted on everything.”

To show Violet the human rights outlined in the Declaration of Independence, he heads in a different direction from Plato and leads with a line from Superman: The Movie Superman tells Lois Lane, “I’m here to fight for Truth, Justice, and the American Way.” Burriesci writes, “Superman is the personification of the America the founding fathers wanted for you, Violet; learned, humble, strong, and absolutely committed to principles. [ . . . ] Like Superman, you have accidentally grown up in a unique environment that grants you immense powers and privileges.” His prescription: Don’t abandon those principles.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels share a chapter that concerns their jointly written 1848 manuscript, The Communist Manifesto, which treats class conflict. Burriesci describes one of his early jobs at an office supply store that later was put out of business by big-box competition. Then he discusses Marx and Engels’ prediction that, among their other pronouncements, “modern industrialized capitalism inevitably produces two classes whose interests are naturally at odds.” It’s a pertinent example of how texts from previous centuries often relate directly to today.

At the beginning of this book, Burriesci puts forth his key intention for Violet: “These writers can teach you how to think, not what to think.” He succeeds in laying out the groundwork with easy-to-understand treatments of writings and the history they convey. I especially liked his discussions of the earliest texts, and was slightly less enamored to learn about his own shortcomings. Nevertheless, I’ll return to Dead White Guys again and again. It’s a first-rate primer.

One additional note. Since writing this book, Burriesci and his wife Erin had another baby. Burriesci says, at the back of this book, the next book will be for their son Henry. Along with Henry, I look forward to reading it.