Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

Four lines into the opening poem “The Bread” from Jeffrey Bean’s award-winning new chapbook Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, the speaker recounts the defining experience of his life: sitting down at a restaurant table with a girl. Doling out description with subtle music that captures the slowly evolving intimacy of the situation, the stanza quite literally sets the table for the flash of love’s bittersweet onset that occurs in the stanza’s final line. While the straightforward description of the scene details the outward circumstance of the meeting, the allusion to Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “God’s Grandeur” captures the true scope of the meeting’s importance:

The bread, the salad, simple, oiled.

The coats on hooks, exhaling winter smoke.

The hand that was mine, the knuckles, the table, smooth oak.

The girl I’d come to meet, the sky behind her hair, shook foil.

Later in the same poem, when the speaker candidly states, “I had been lonely, I had been hungry as a rat,” there is a sense of discovery in the admission that feels fresh, as if finding love has made him reconsider exactly how he’d been hungry for connection and the bizarre ways that hunger had manifested itself. Whether considering the fevers of adolescence, the art of an Old Master, or the concerns of family life, the poems in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window deal with that desire for connection and the unsettling reality that the connection, once found, can’t last. By turns, tender, funny, sobering, and surreal, Bean’s poems are pulled into surprising territory by the sound of their saying.

The chapbook’s three poems based on the paintings of Dutch master Johannes Vermeer, of which the title poem is one, are prime examples of this. Vermeer’s paintings, with the tranquility of the domestic interiors and scenes they depict, provide rich subject matter for Bean’s clarity. In just a few opening lines from “Vermeer: Woman Putting on Pearls,” Bean captures the warmth of the painting and the expression on the soon-to-be mother’s face as she enjoys a moment of true contentment alone in her light-filled room: “Sometimes you get a minute or two, / nobody needs you for once, your body’s buoyed / by that grass-and-river feeling after lunch.” Astutely arranged within the chapbook to resonate with its loose progression from youthful experience to parenthood and family life, the poems elicited by Vermeer’s paintings provide some of the chapbook’s most meditative moments.

I’m not surprised, having had Bean’s instruction in graduate school, that the joy he takes in word-play, non-sequiturs, moments of apt surrealism, and the challenges of form, present in his first book, Diminished Fifth, shows up again in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. While Diminished Fifth overflowed with these tendencies, the poems in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window make more sparing and integral use of them to undergird the poems’ deeper meanings. Whether writing a sonnet or a list poem, Bean creates a conversational tone. An attention to emotional coherence and intellectual clarity, paired with a will to be weird, gives Bean’s writing a wholesomely unhinged quality. Whether his speaker is considering the moral of a parasite’s plight: “Everybody knows the lice are lonely. / And yet we go baring / our hairy necks in the park,” noticing that his daughter “claps the way Chuck Berry plays guitar,” or deciding that geraniums smell like “a cloth that cleans guns” and his “brother leaving for the lake,” the strangeness feels apt.

Bean’s ability to fuse humor with a sense of pathos is on full display in his poem “The Joy of Painting,” which finds the poem’s speaker peering over the shoulder of PBS’s own old master, Bob Ross. Watching television before bed, the speaker is drawn in by Ross’s enthusiasm for painting. The speaker’s enjoyment, however, takes a poignant turn when he notices the sun spots on the artist’s hands and remembers Ross is already dead. From this realization, “an old, tired thought” about his own death and the eventual death of his sleeping family deepens his art appreciation:

tonight on TV Bob Ross is happy

and alive, using odorless paint thinner, saying

let your imagination run wild and let it go,

here, you can do anything that you want to,

and he’s making a huge mountain struck by light,

and in the face of this and the death all over

his hands, I’m drinking warm milk and hoping

I can drift off to sleep without trouble. And Bob

is washing his brush now, and drying it, saying,

just beat the devil out of it, and now he’s painting

a happy little tree, almost like the one he imagined.

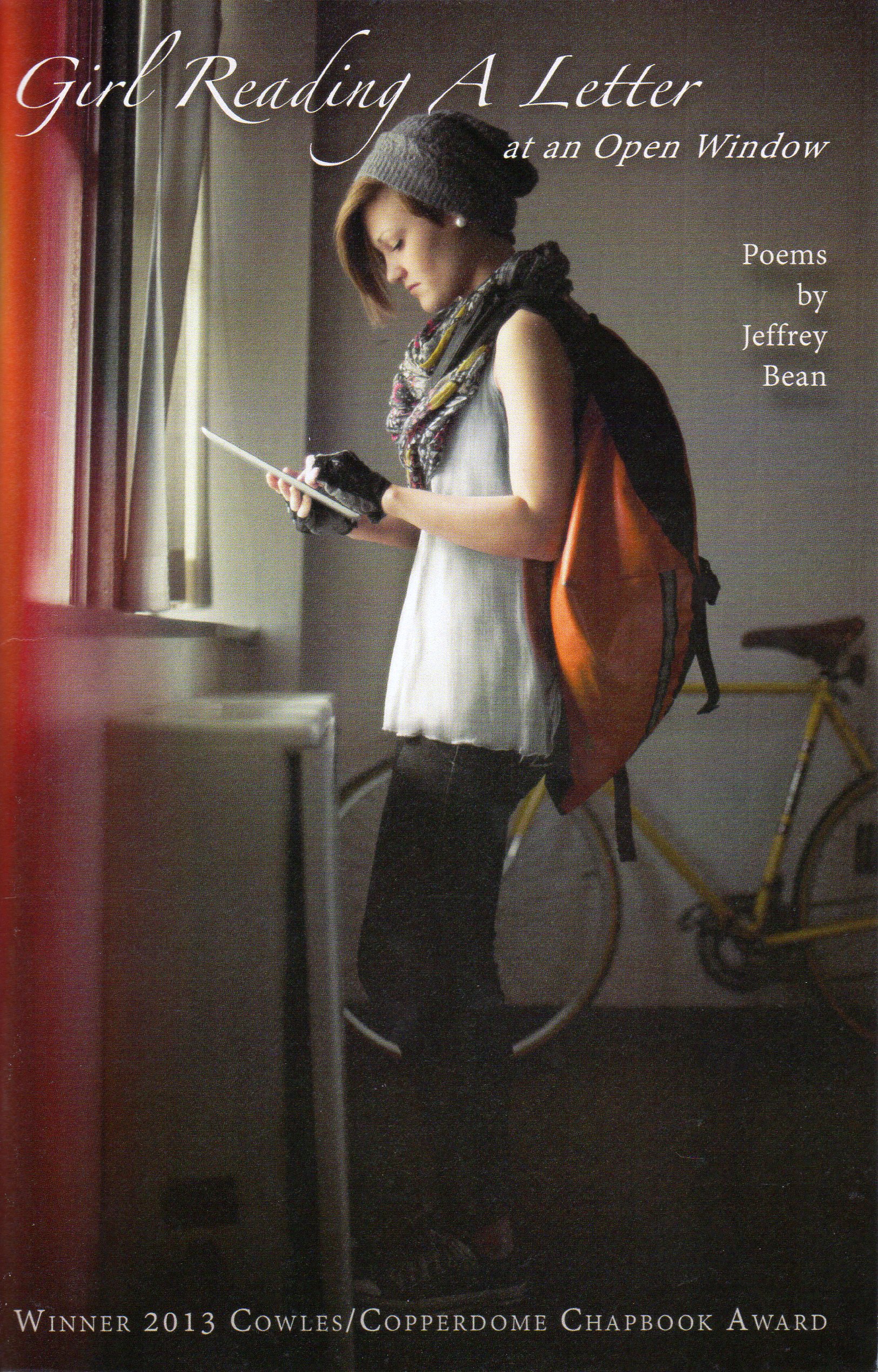

In the photographic update of Vermeer’s painting that appears on the cover of the chapbook, the casually elegant ingénue reads from a tablet rather than a handwritten letter, and the light filters through the window’s vertical blinds rather than draperies and leaded glass, but the human drama remains unchanged. The quotidian is made luminous and psychologically complex by the photograph’s composition. In the poems of Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, the commonplace is rescued from inconsequence by Bean’s imagination and ability to show the movement of thought on the page. Whether the speaker is finding the happy little tree of immortality, recalling family life through a free-association about the smell of geraniums, or considering the meaning of love and lack, the compositions lead the reader to the matter’s beating heart.